How One Startup is Breaking Nvidia’s Memory Bottleneck

How Weka is Solving AI’s Trillion Dollar Memory Problem.

It takes time to create work that’s clear, independent, and genuinely useful. If you’ve found value in this newsletter, consider becoming a paid subscriber. It helps me dive deeper into research, reach more people, stay free from ads/hidden agendas, and supports my crippling chocolate milk addiction. We run on a “pay what you can” model—so if you believe in the mission, there’s likely a plan that fits (over here).

Every subscription helps me stay independent, avoid clickbait, and focus on depth over noise, and I deeply appreciate everyone who chooses to support our cult.

PS – Supporting this work doesn’t have to come out of your pocket. If you read this as part of your professional development, you can use this email template to request reimbursement for your subscription.

Every month, the Chocolate Milk Cult reaches over a million Builders, Investors, Policy Makers, Leaders, and more. If you’d like to meet other members of our community, please fill out this contact form here (I will never sell your data nor will I make intros w/o your explicit permission)- https://forms.gle/Pi1pGLuS1FmzXoLr6

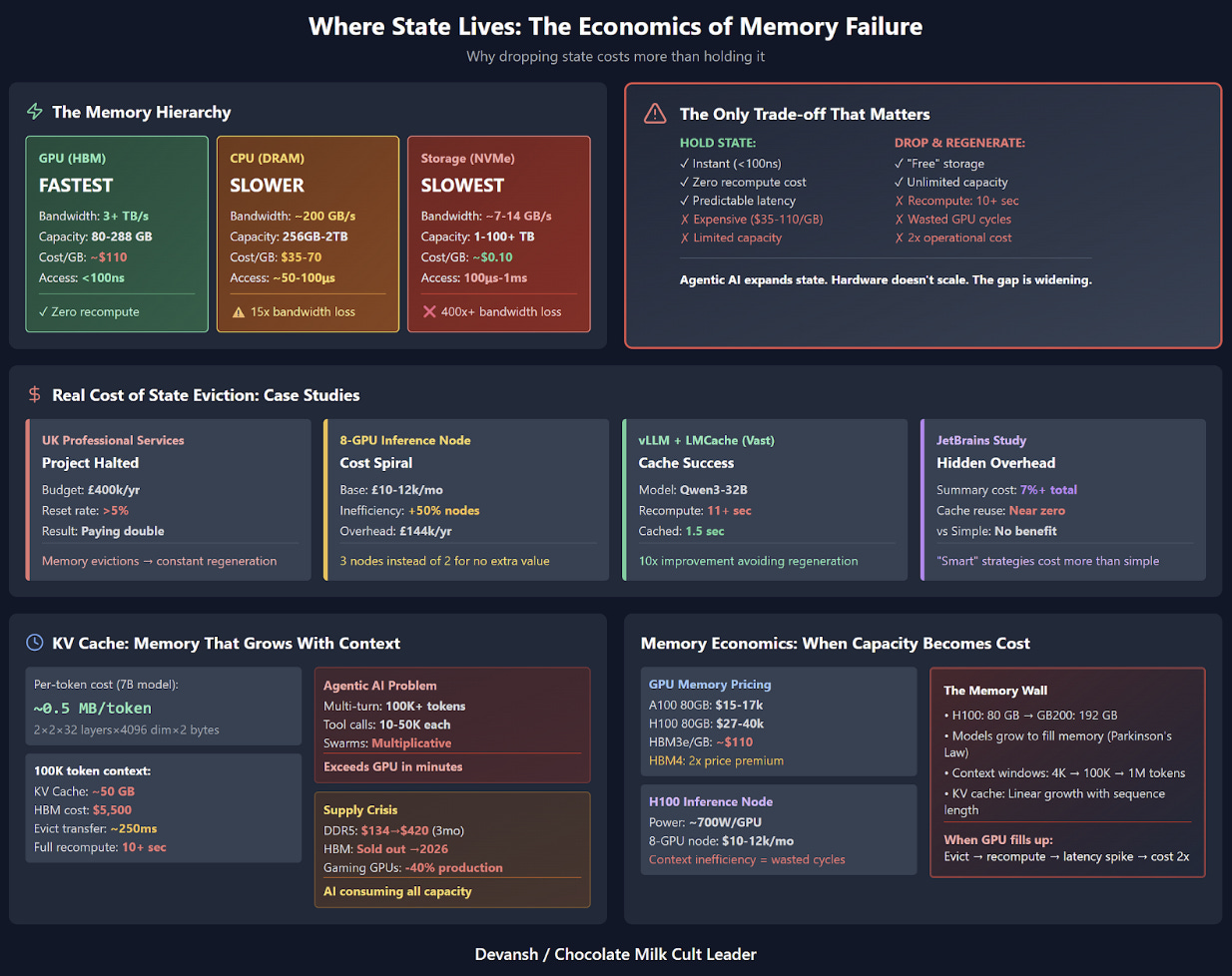

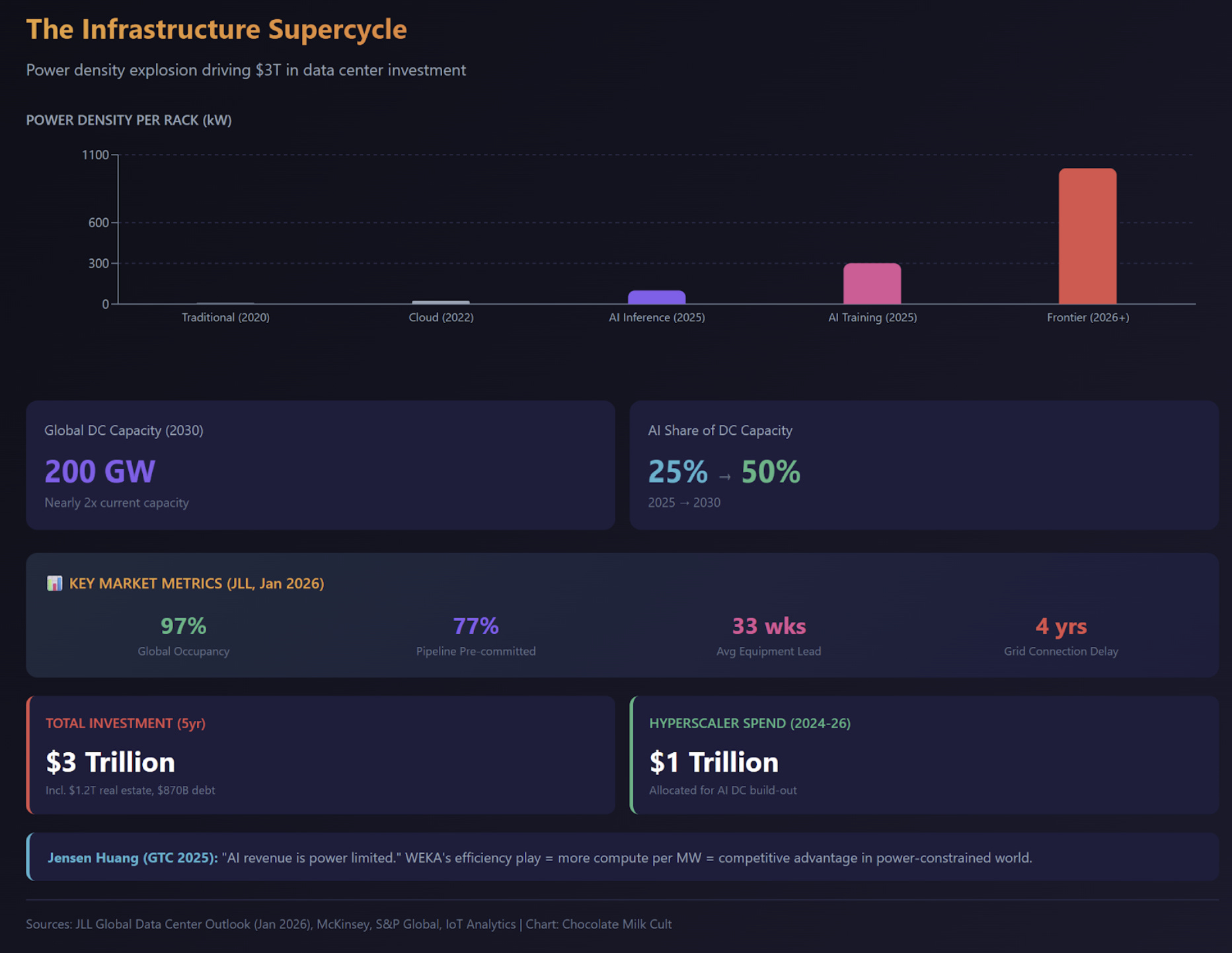

As AI evolves from simple chatbots into complex, reasoning agents, the systems are generating and relying on vast amounts of “state” — their working memory. This state is already orders of magnitude larger than what can fit in a GPU’s high-speed memory. This means that the next great bottleneck is not compute; it is memory.

Every time a system’s working memory overflows, it must either crash or forget. Forgetting forces the system to re-read and re-process context from scratch — a “recompute tax”. That forgetting is expensive. On a 128,000-token context window, re-processing can cost 30+ seconds of GPU time per request. At H100 rental rates, that’s dollars per conversation — not cents. Scale that to thousands of concurrent users, and you’re burning GPU budget on work you already paid for once.

This article is a deep dive into WEKA, a company that builds infrastructure specifically designed to solve this problem. We will decode what they actually built, why it matters, and where it fits in the current AI stack. In more detail, this article will help you understand:

Why agentic and long-context systems make memory a first-class economic constraint

How WEKA is turning what used to be “storage” into something that behaves like memory

What the architecture actually is — and what makes it different

Where performance gains really come from (not just benchmarks, but mechanisms)

How those gains translate into economics: GPU utilization, cost-per-session, etc.

Where WEKA fits into the current AI infra stack — not hypotheticals, but real-world

What bet they’re making about the future — and what happens if they’re right

Executive Highlights (TL;DR of the Article)

Skip to Section 4 (“What WEKA Is Actually Trying to Build”)if you already understand the KV cache economics problem.

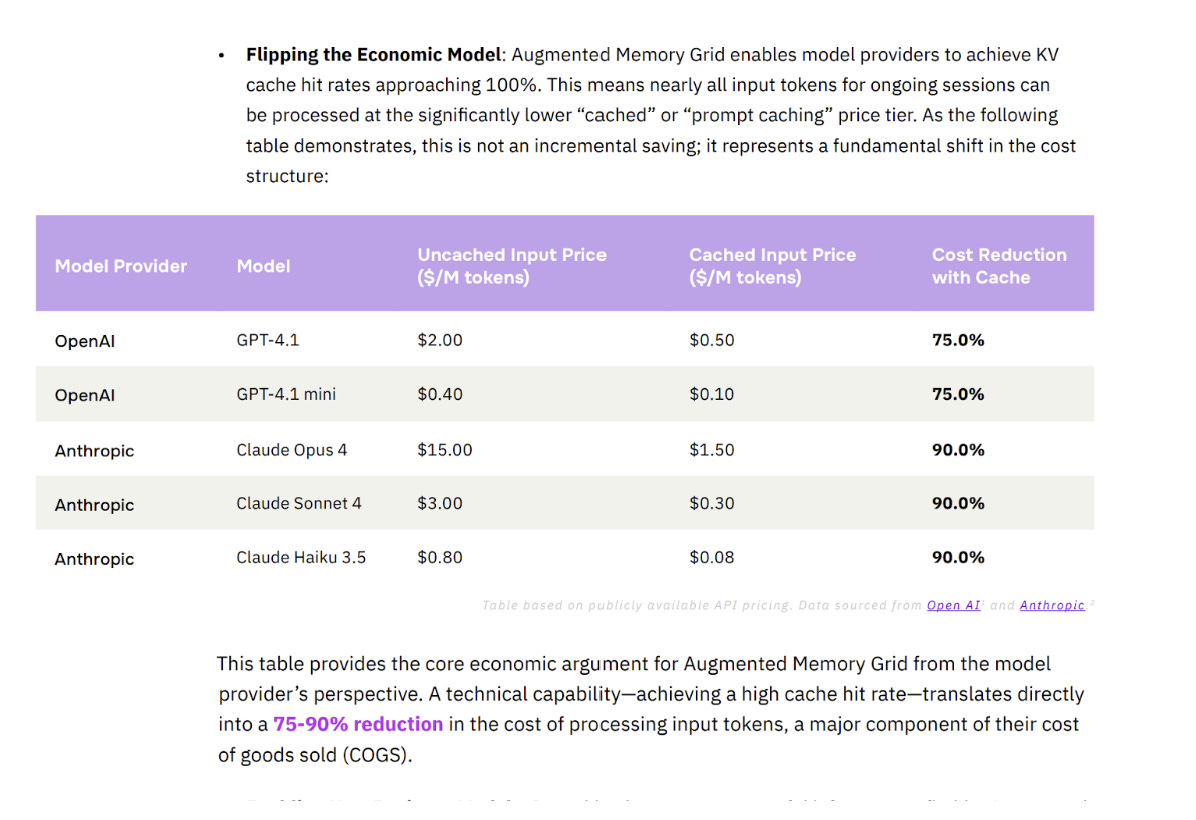

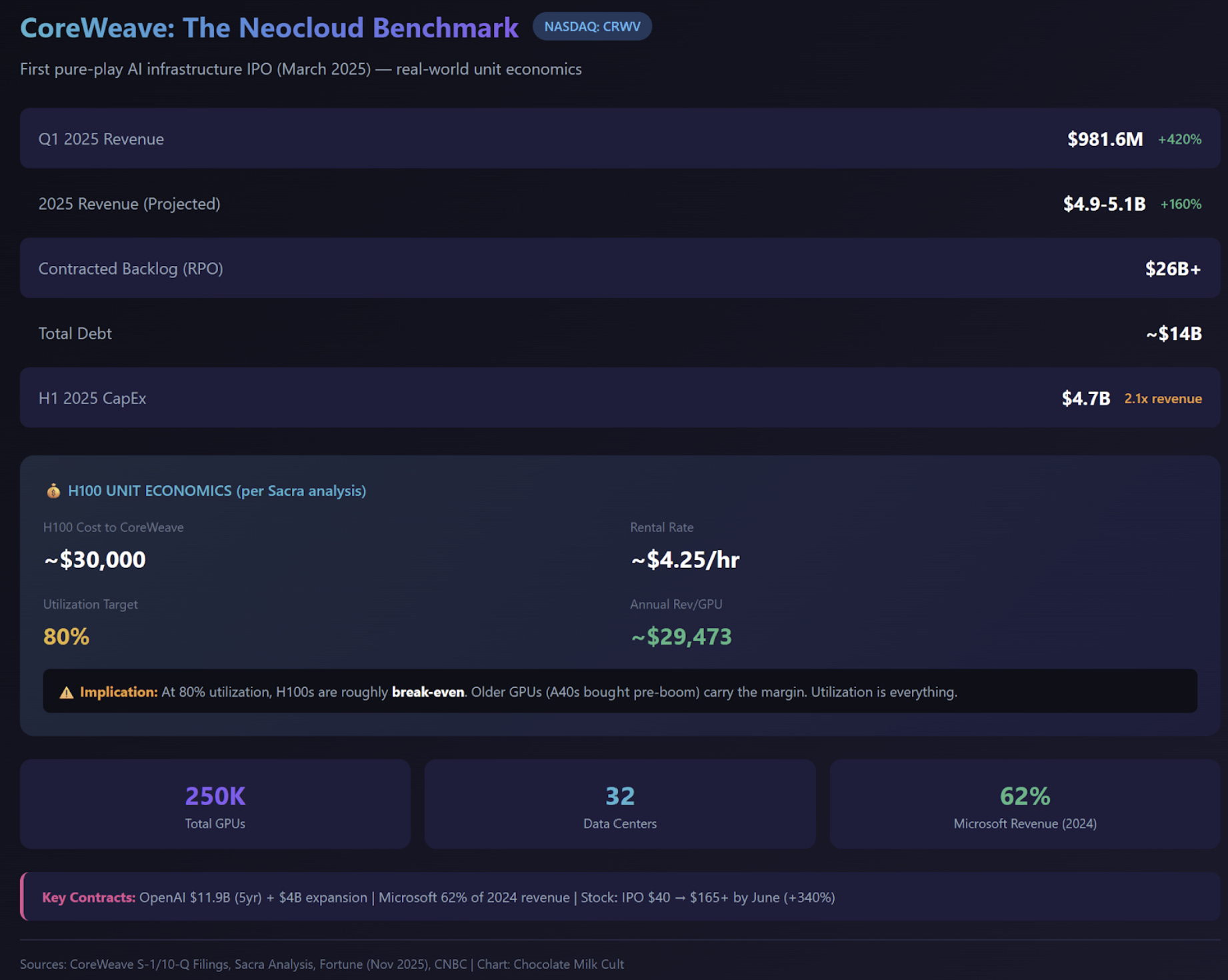

The core thesis: GPU memory (HBM) is the actual bottleneck for stateful AI, not compute. When your 128k-token KV cache gets evicted because HBM filled up, you pay a “recompute tax” — 39 seconds of prefill time per cache miss at Llama 70B scale, which is ~$0.03/request. At 30% cache miss rates across 80 requests/hour, that’s $4,800/month per GPU in pure waste. WEKA’s bet is that storage can be made fast enough to act like memory, turning what was a volatile, scarce resource (HBM: 80GB, ~$100/GB) into a persistent, abundant one (NVMe: petabytes, ~$0.20/GB).

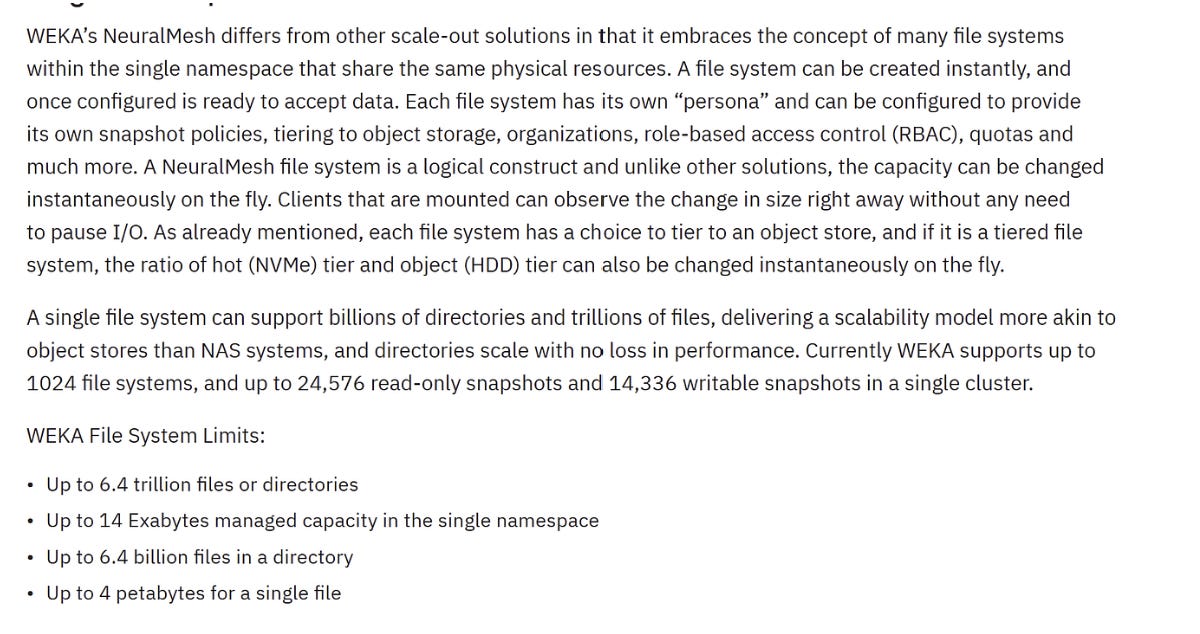

The architecture that makes this work: WEKA’s NeuralMesh bypasses the Linux kernel entirely — runs its own RTOS in user space, uses RDMA to skip TCP/IP, and distributes metadata via consistent hashing instead of centralized servers. The result: The result: 100–200 microsecond latency instead of 1000+ µs (or under very heavy loads, 1ms instead of 5+), 269 GiB/s sustained throughput across 8-node clusters, and metadata performance 2x Lustre’s (1,753 vs 895 kIOP/s). This isn’t faster drives; it’s eliminating the software bureaucracy between drives and GPUs.

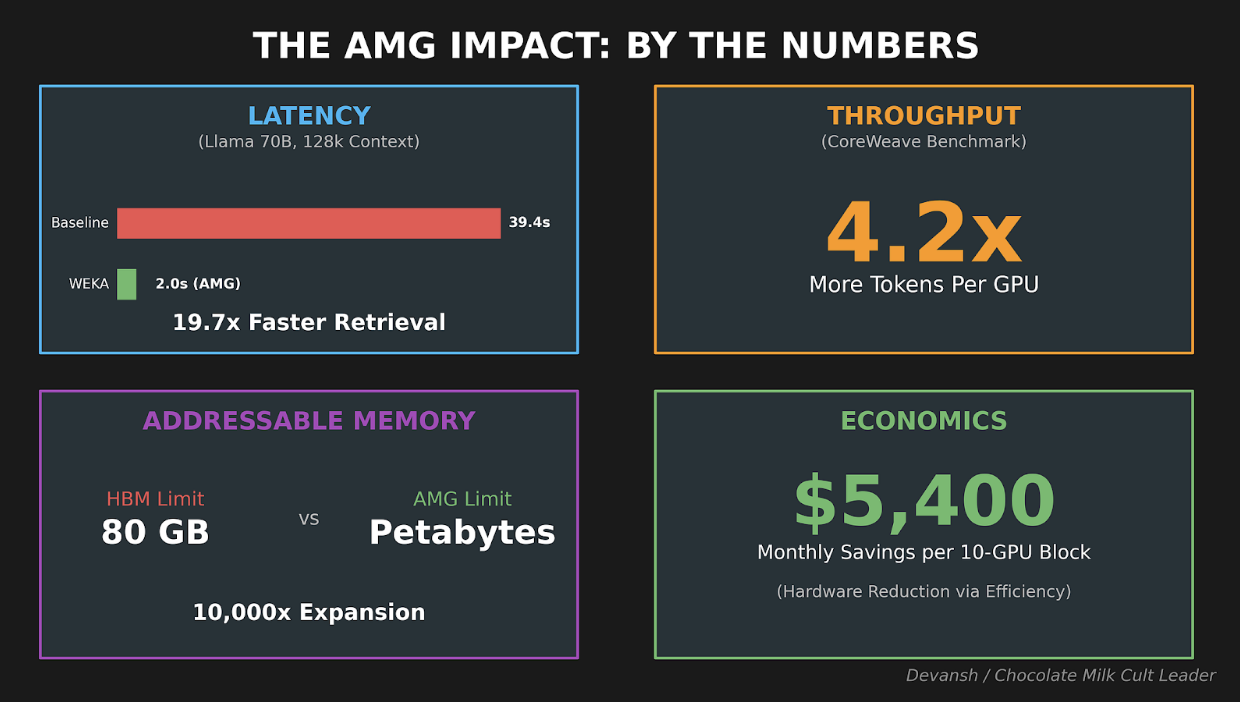

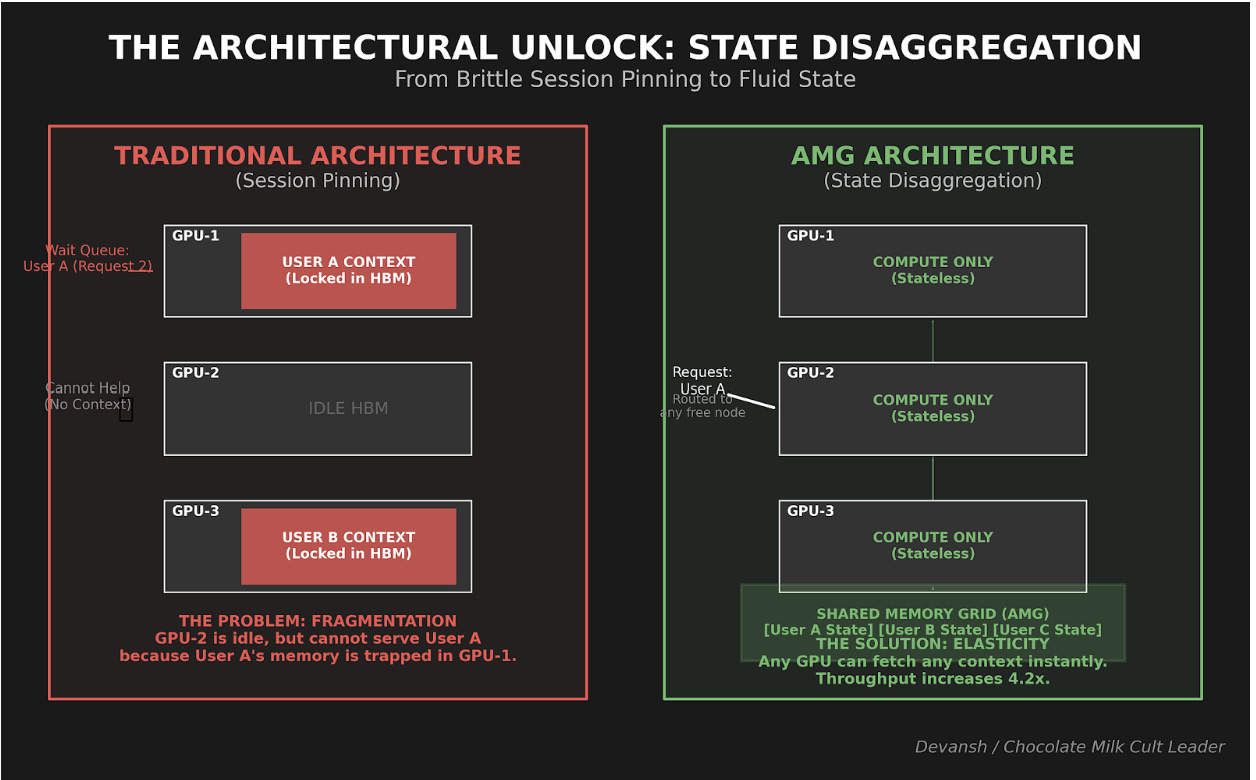

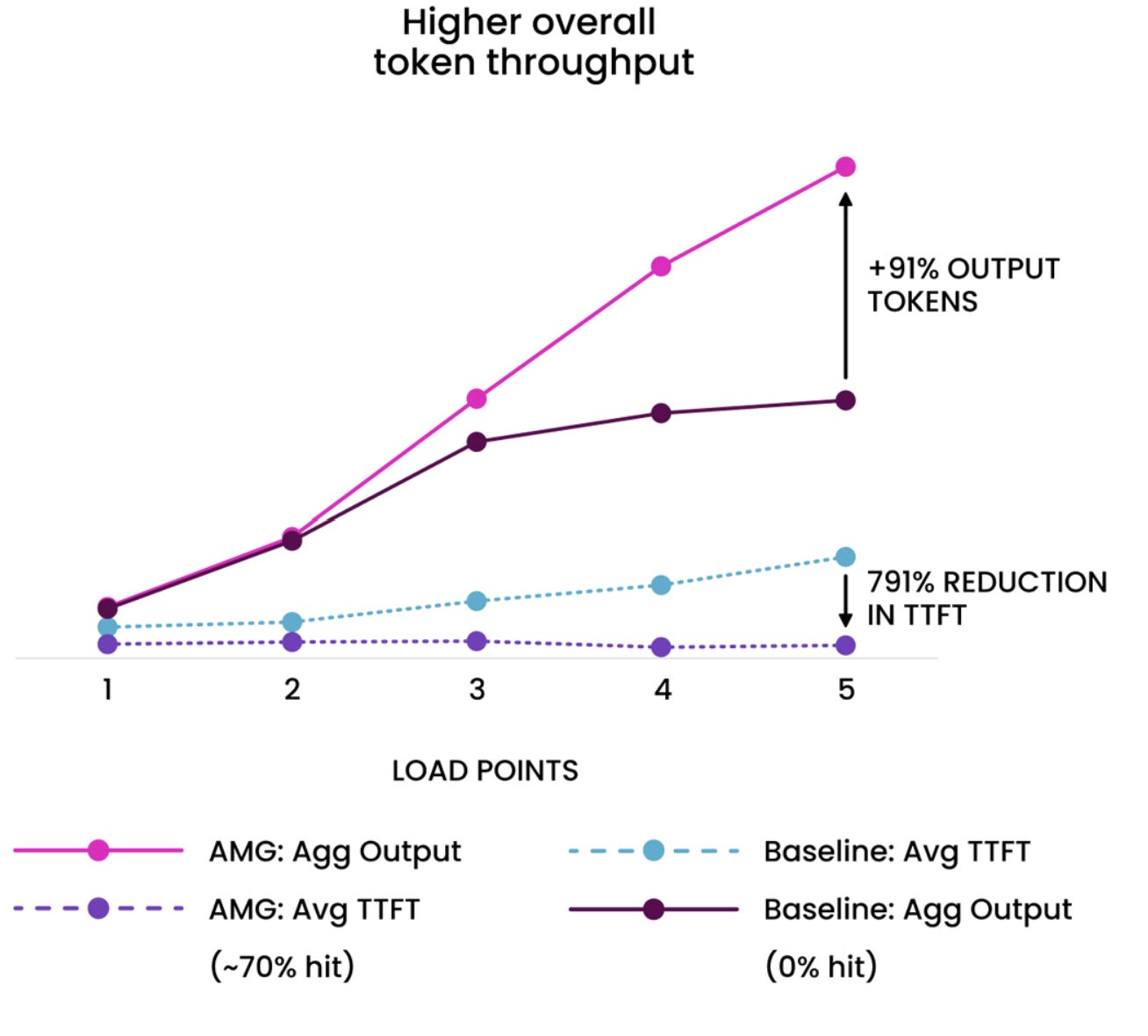

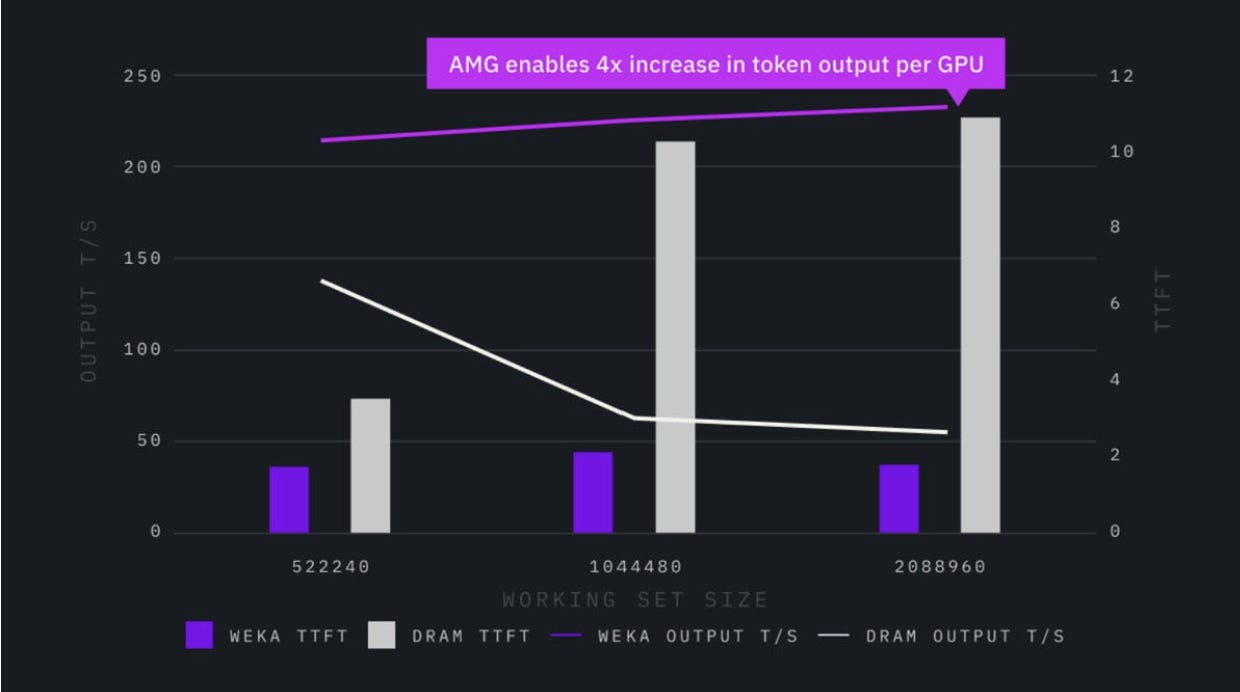

AMG is the wedge into AI specifically. GPUDirect Storage lets NVMe DMA directly into GPU HBM — no staging in system RAM. CoreWeave’s production testing showed 4.2x more tokens generated per GPU and 20x improvement in time-to-first-token on 128k context. The unlock: session pinning dies. Your GPUs become stateless compute drawing from a shared memory pool. Any GPU serves any request by fetching state from NVMe in sub-second latency. Fragmentation disappears, fault tolerance improves, elastic scaling actually works.

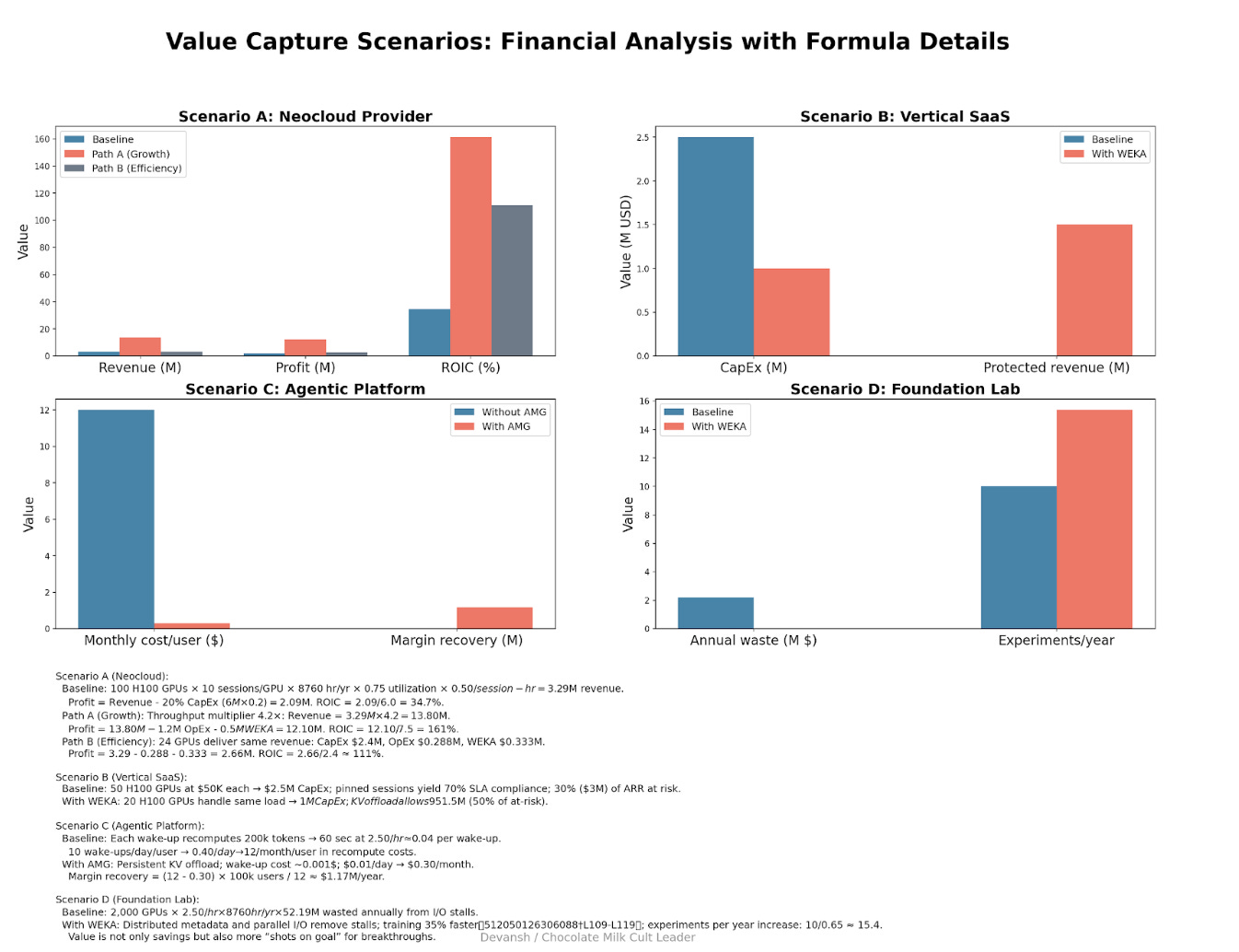

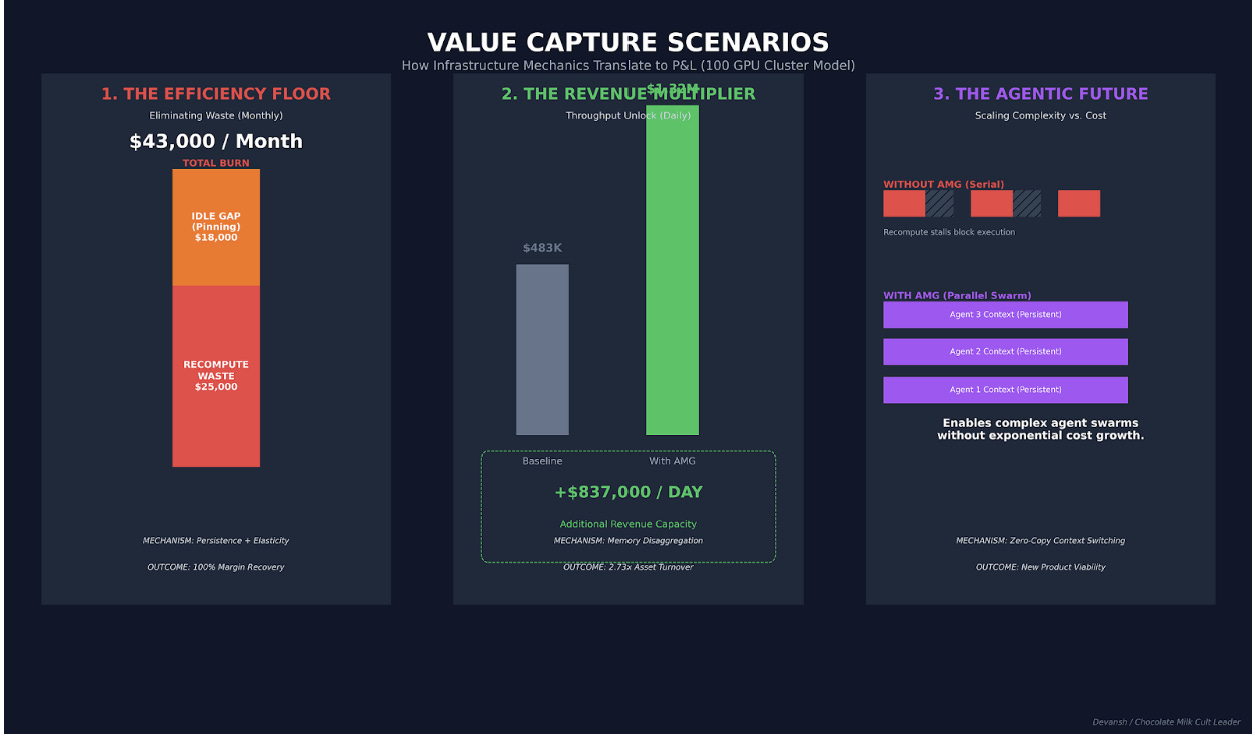

The financial arbitrage: WEKA trades storage dollars for compute dollars. A 100-GPU neocloud cluster running at 75% utilization with baseline storage generates ~35% ROIC. Add WEKA, apply the 4.2x efficiency multiplier, and ROIC jumps to 161% — same hardware, 4x the throughput, margins expand from 63% to 88%. Or flip it: deliver the same revenue with 24 GPUs instead of 100, free up $3.6M in capital, triple your ROIC. This is why neoclouds adopt — it’s existential to their business model.

The bet WEKA is making: If AI stays stateless (single-turn, disposable context), they’re a niche storage vendor. If AI becomes stateful (agentic, multi-turn, accumulating), they’re positioned at exactly the seam where old infrastructure breaks. The recompute tax, session pinning waste, and context loss are real costs someone will solve — whether WEKA captures that value depends on execution, but the value gets created regardless.

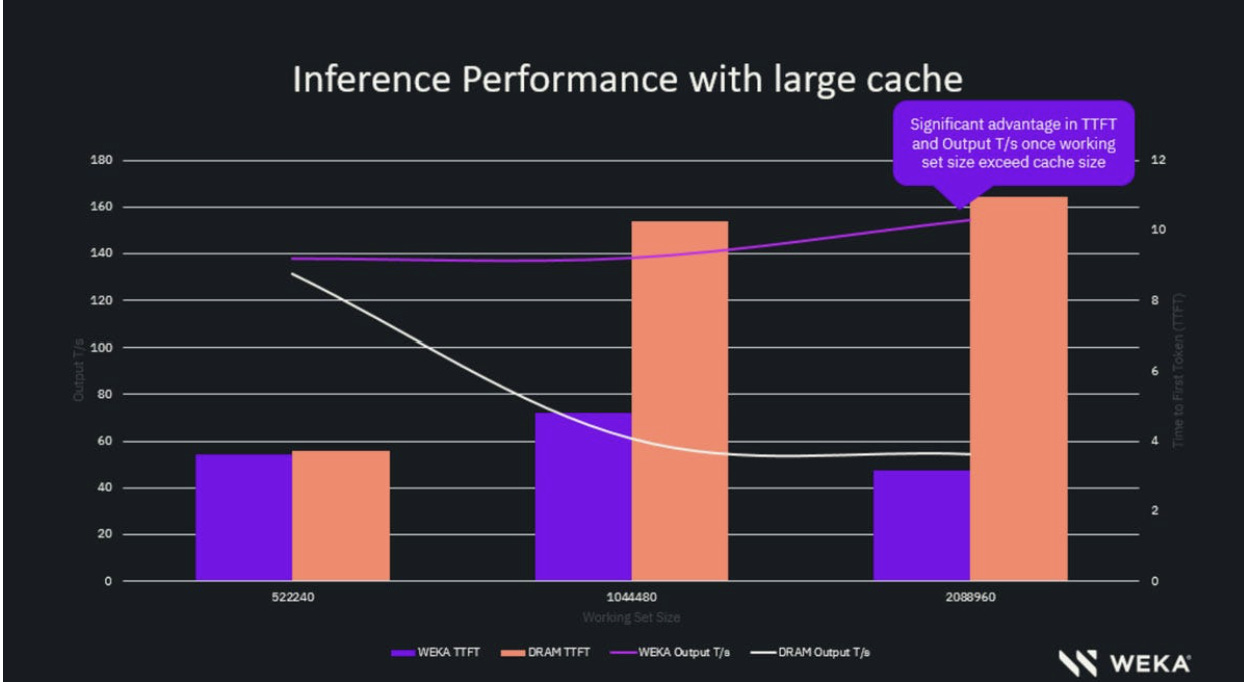

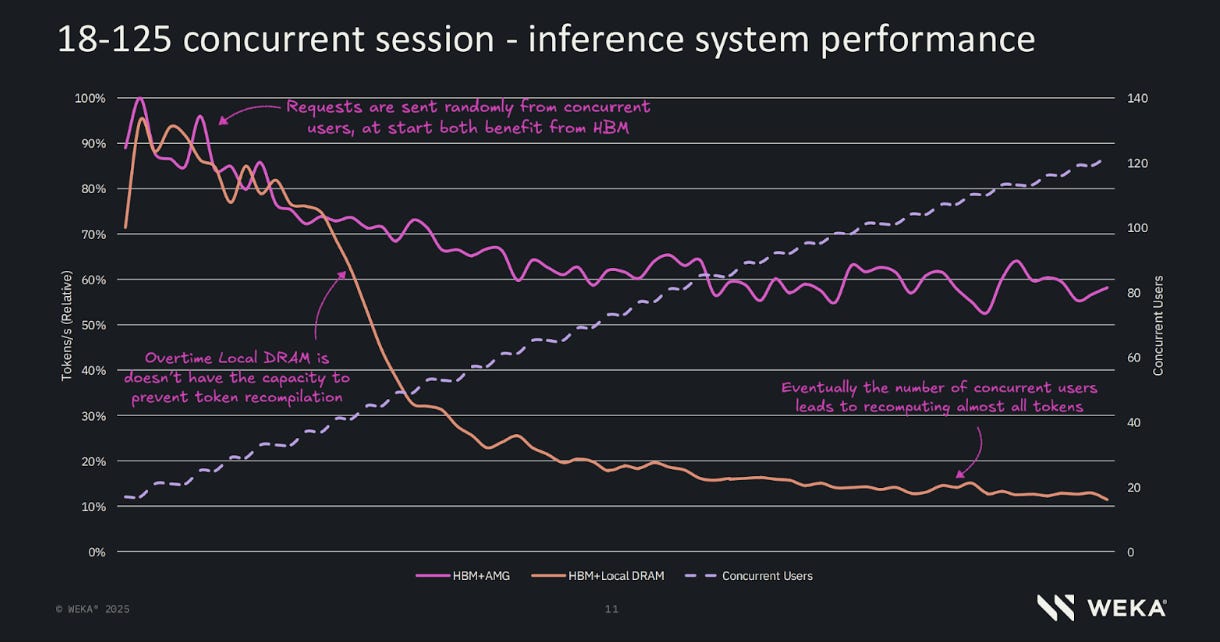

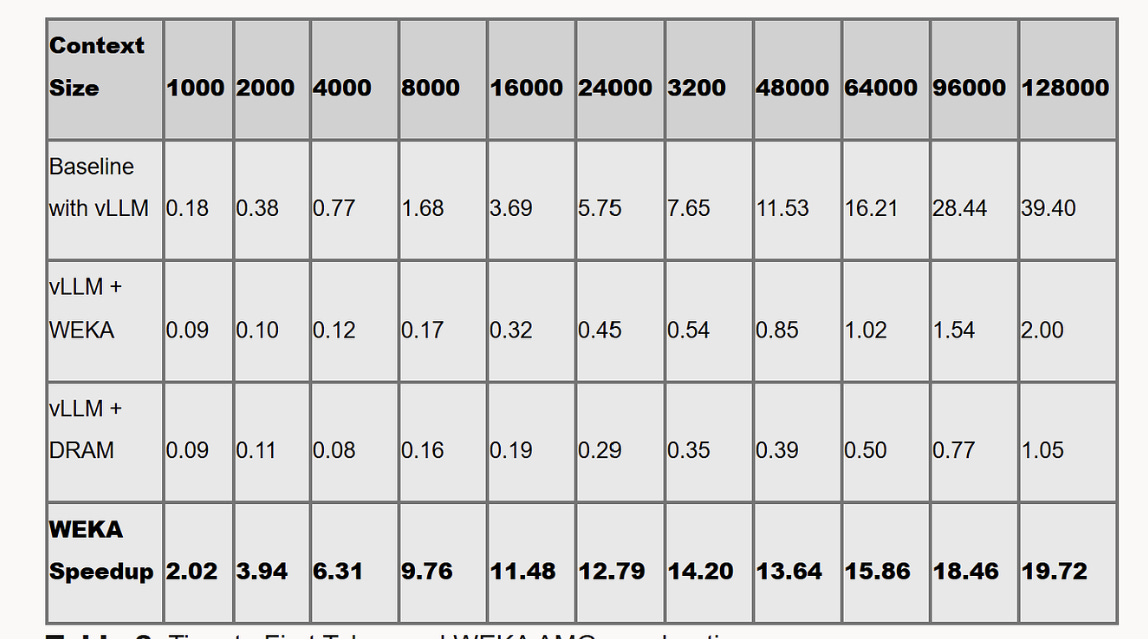

(Important note — this report uses some single session/user benchmarks, but the trend is towards deprecating single-user/session benchmarking results like these, because the lack of concurrency is too far removed from real-world production inference and/or agentic workload scenarios. We do it for simplicity and additional data, but consider that factor when looking at the numbers. Concurrent benchmarks, such as the one shared below should be considered the gold standard when evaluating a solution like WEKA).

I put a lot of work into writing this newsletter. To do so, I rely on you for support. If a few more people choose to become paid subscribers, the Chocolate Milk Cult can continue to provide high-quality and accessible education and opportunities to anyone who needs it. If you think this mission is worth contributing to, please consider a premium subscription. You can do so for less than the cost of a Netflix Subscription (pay what you want here).

I provide various consulting and advisory services. If you‘d like to explore how we can work together, reach out to me through any of my socials over here or reply to this email.

Are you a startup that wants similarly deep coverage? Send me a message, and let’s talk. I charge no money for deep-dives (nor will any financial compensation be accepted); all I ask is that you do interesting/useful work and transparently share data that I can use for our analysis. For access to our internal data/assessments of other startups, send me an email — devansh@svam.com.

1. The Bare Minimum Vocabulary

To make sure we’re speaking the same language, here is a list of the very important

Inference

Beyond the simple “model goes brrr to answer question”, your model.call() does two distinct things:

Prefill. It processes the entire input prompt at once. This is matrix multiplication heavy — exactly what GPUs are good at. More sequences in parallel = higher utilization.

Decode. It generates one token at a time. Each new token depends on the entire history of prior tokens. This phase is dominated by memory reads/writes rather than raw math.

If you treat prefill and decode the same, you either underutilize compute (during prefill) or blow up latency (during decode).

Note: Weka’s value proposition lives almost entirely in the friction between these two phases.

State

The context required for the model to continue a thought. In a chatbot, state is the conversation history. In an agent, state is the plan, the tools, and the memory of previous steps. If you lose state, the model effectively gets amnesia.

Memory vs. Storage

This is a crucial technical distinction, especially since most common speech uses the terms interchangeably.

Memory (HBM/DRAM): The “Penthouse.” Extremely fast, extremely small, volatile (data vanishes when power cuts), and aggressively expensive (~$100/GB).

Storage (NVMe/SSD): The “Warehouse.” Slower, massive, persistent, and cheap (~$0.20/GB).

Historically, systems were designed with a hard boundary between the two. Memory was for computation; storage was for safekeeping.

KV Cache

The technical term for “State.” When a model reads your prompt, it calculates a massive set of Key-Value pairs representing the relationships between words.

Think of the KV Cache as the transcript of the model’s understanding. If you keep the transcript, the model can answer follow-up questions instantly. If you delete it, the model must re-read the entire book to understand the context again.

These 4 terms are enough to serve as a foundation for our exploration into the space. To understand why Weka’s work is worth studying, we must also understand how we’re currently handling memory and why that’s not working.

2. Where State Actually Lives (And Why This Is Starting to Fail)

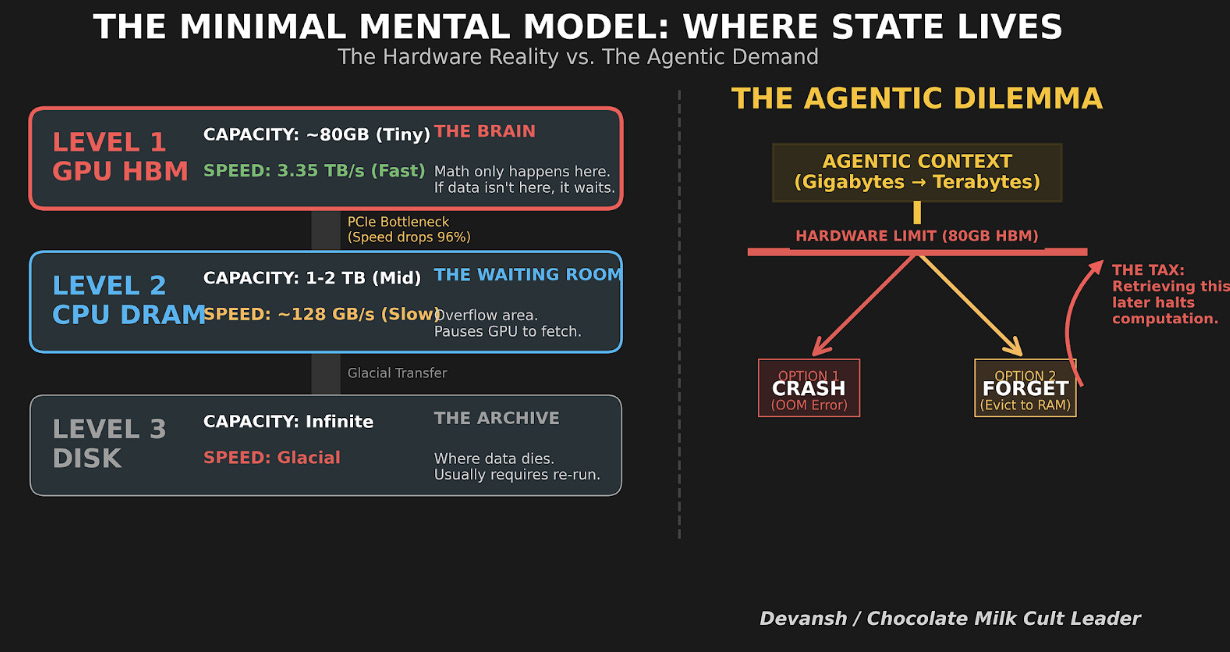

An AI system’s state can live in a few places, each representing a fundamental tradeoff between speed and size. Visualizing this simple hierarchy is key to understanding the entire problem.

On the GPU (HBM): The fastest, closest, and smallest tier of memory. This is the ideal place for the model’s active working state.

In System Memory (DRAM): Slower and farther away from the GPU’s processors, but significantly larger.

On Network Storage (NVMe): The slowest of the three, but vastly larger and, crucially, persistent — it remembers even when the power is off.

When GPU memory fills up, state gets pushed to CPU memory. When CPU memory fills up, state gets pushed to storage or simply dropped. And when state gets dropped, the system has to regenerate it — which means redoing the work that created it in the first place. This is the only trade-off that matters at the infrastructure level: hold state, or redo work.

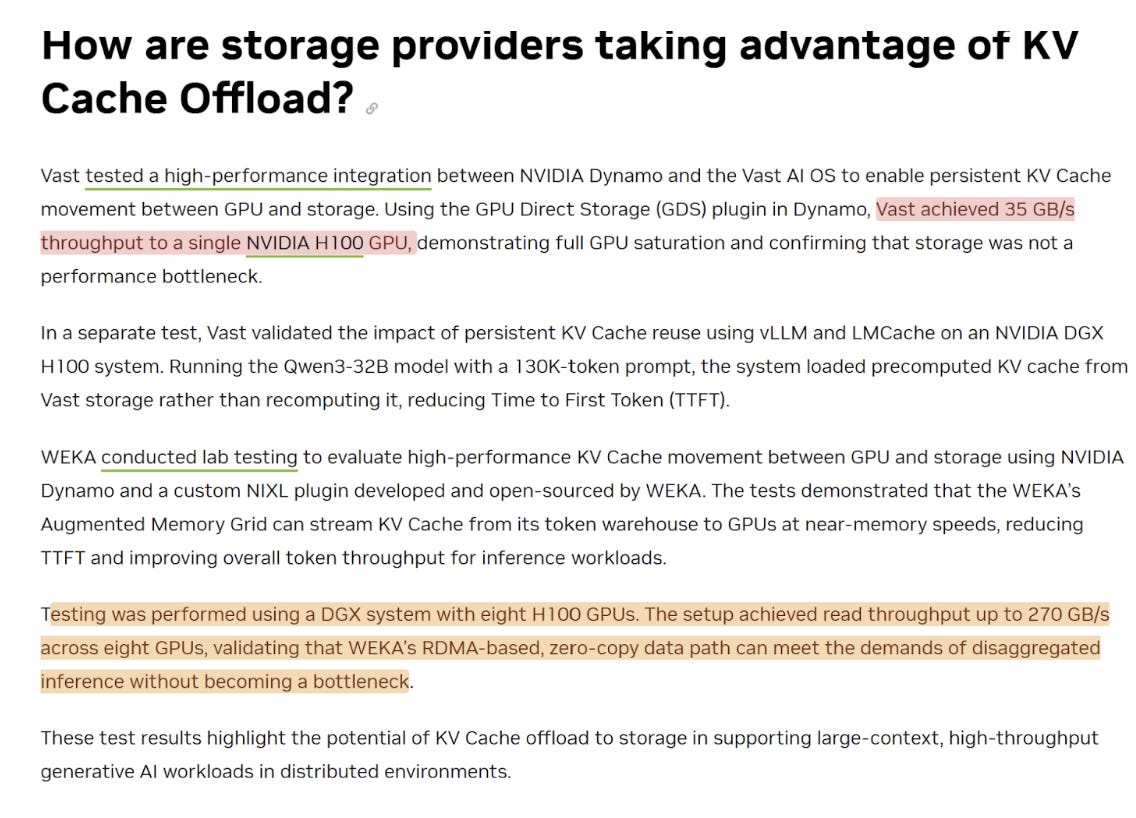

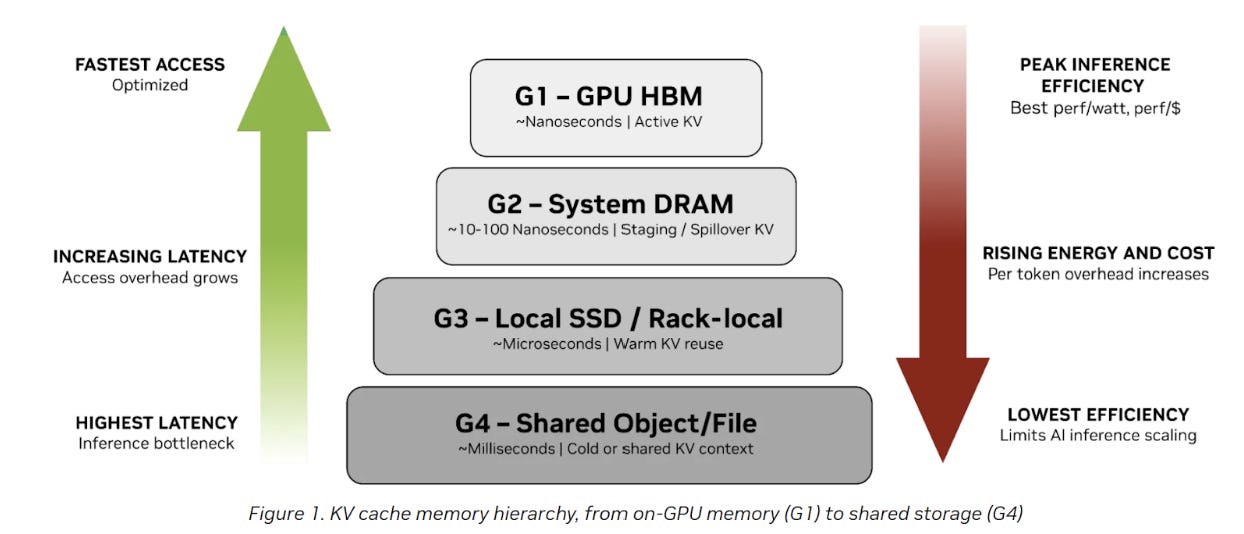

NVIDIA and WEKA have formalized the memory tiers for AI factories. I expect this terminology to become more mainstream going forward so it is worth taking a second to make note of it:

G1 (GPU HBM) for hot, latency‑critical KV used in active generation

G2 (system RAM) for staging and buffering KV off HBM

G3 (local SSDs) for warm KV that is reused over shorter timescales

G4 (shared storage) for cold artifacts, history, and results that must be durable but are not on the immediate critical path

Based on this classification, Weka would be in 1.5. We’ll cover this in more detail, and its implications going forward.

The key takeaway is that latency and efficiency are tightly coupled: as inference context moves away from the GPU, access latency increases, energy use and cost per token rise, and overall efficiency declines. This growing gap between performance-optimized memory and capacity-optimized storage is what forces AI infrastructure teams to rethink how growing KV cache context is placed, managed, and scaled across the system.

Agentic AI — multi-turn conversations, tool-using agents, persistent reasoning — keeps increasing how much state you want to hold. An agent coordinating a complex task might accumulate hundreds of thousands of tokens of context. A swarm of sub-agents multiplies that further.

Hardware memory doesn’t scale to meet that demand. GPU memory is physically constrained. CPU memory is expensive and still volatile.

The question becomes: can storage be made fast enough to act like memory?

That’s the question WEKA is answering. Before we look at their solution, we need to understand why these failures show up the way they do, and how they translate directly into latency spikes and cost explosions. Let’s do that next.

3: Why Modern AI Breaks Old Assumptions

The breakdowns we just described aren’t theoretical. They surface in production systems in a few very specific, repeatable ways. Understanding these failure modes is important because each one has a clear performance signature and a clear economic cost.

3.1 The Recompute Tax

Imagine you’ve fallen behind on keeping up with an important email thread because you were too busy playing Age of Empires on company time. Now your dumbass needs to send a deliverable immediately b/c your Khoon-Ki-Pyaasi Daayan boss always ships you with last-minute work that he’ll take credit for. So you send a long prompt of the entire email chain + documents. The model processes it, building up KV cache as it goes. That processing (called “prefill”) is computationally expensive — it’s the phase where the model actually “reads” the input. Once prefill is done, the model generates its response using the cached state.

Now you ask a follow-up question. In an ideal system, the KV cache from the first turn is still available. The model only needs to process the new tokens, then continue generating.

But if the KV cache was evicted — because GPU memory filled up, or because the session was routed to a different server — the system has to redo the entire prefill. Every token of context, reprocessed. That’s the recompute tax.

The cost model:

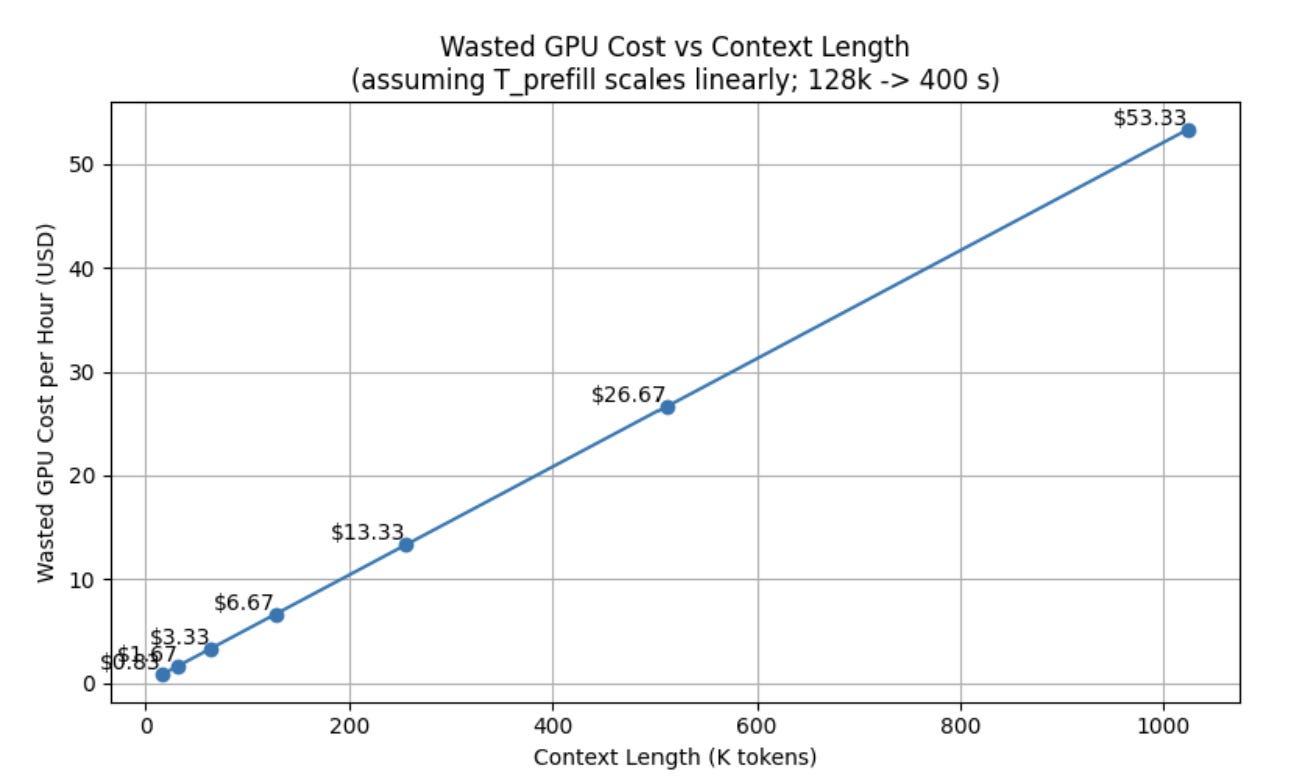

Let’s define the variables:

C = GPU cost per hour

T_prefill = time to prefill a given context length

R = percentage of requests that trigger recompute (cache miss rate)

N = number of requests per hour

The wasted GPU cost per hour is:

Waste = C × (T_prefill / 3600) × R × N

C = $2.50/hour (H100)

T_prefill = 400 seconds (Llama 70B, 128k context) . (Production systems wouldn’t use single-GPU generations, but we’re doing this for simplicity’s sake. )

R = 30% (with sticky routing, no persistent cache)

N = 80 requests/hour (with batching)

Waste = $2.50 × (400 / 3600) × 0.30 × 80 = $2.50 × 0.111 × 0.30 × 80 = $6.67/hour per GPU = $4,800/month per GPU

And this scales superlinearly with context length. The 39.4-second prefill is for 128k tokens. As context windows push toward 1M tokens, prefill times grow proportionally. The recompute tax becomes the dominant cost.

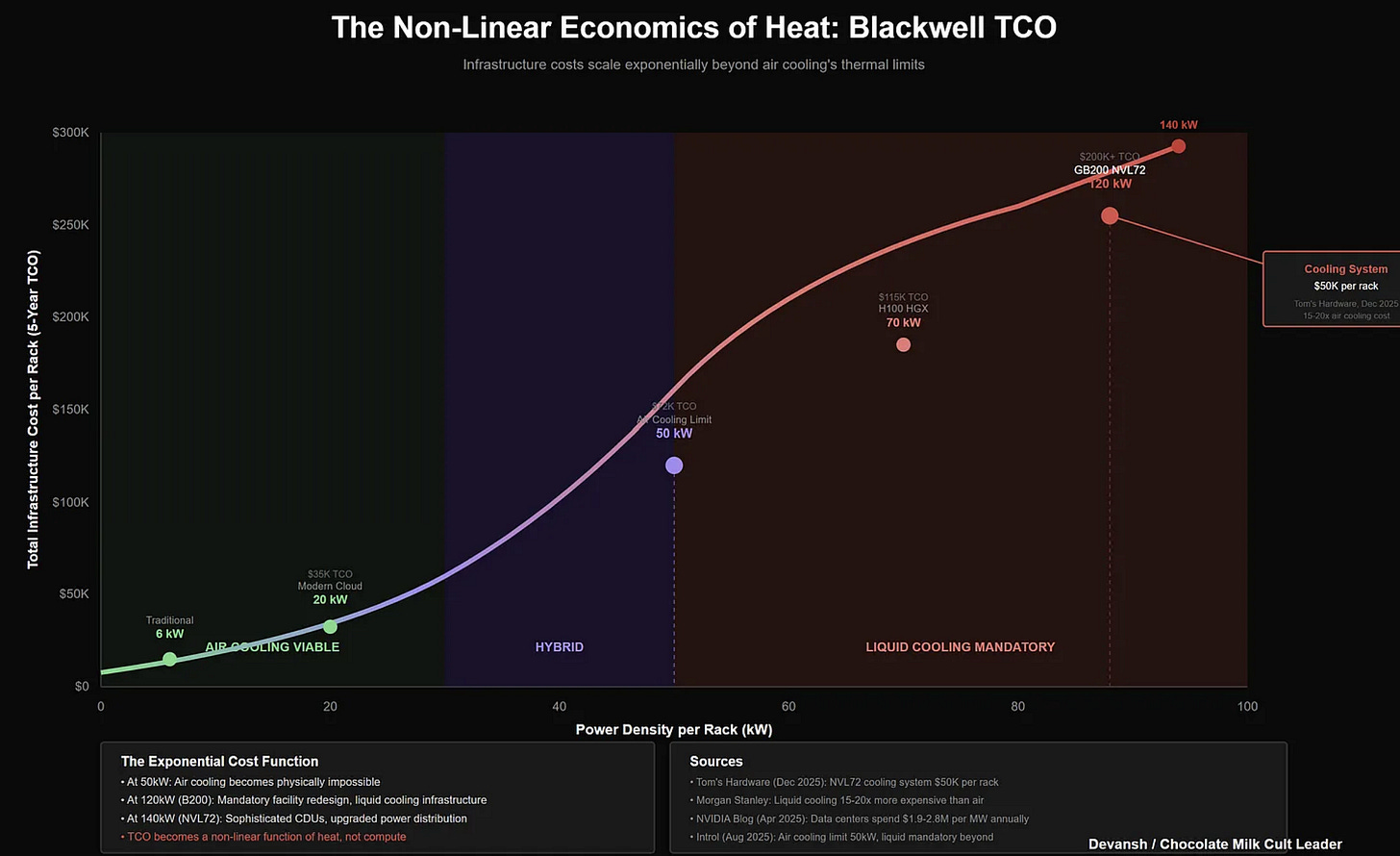

There is another constraint, harder than money: Power. Recomputing a KV cache burns peak GPU wattage (700W+ per H100) to produce heat, not value.

NVIDIA’s analysis shows that AMG delivers 5x better power efficiency than standard storage approaches. Why? Because fetching data from flash consumes a fraction of the energy required to re-run the matrix math to generate it. For data centers capped by the local power grid (where you physically cannot plug in more GPUs), WEKA isn’t just saving money — it’s trading “Hot Watts” (Compute) for “Cool Watts” (Flash), freeing up power budget to run more inference.

3.2 GPU Starvation

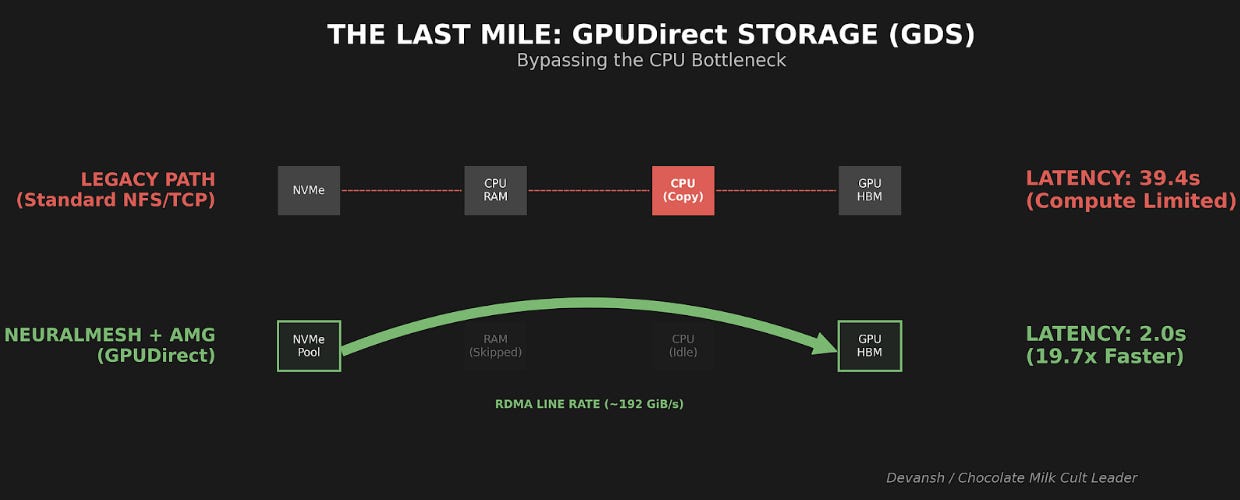

GPUs are incredibly fast consumers of data. Traditional storage stacks (TCP/IP, Kernel context switches) are relatively slow suppliers. When the GPU finishes a batch and requests the next one, there is often a lag while the data navigates the OS bureaucracy.

During that lag, the GPU utilization drops to 0%.

If your data loading stack causes a 100ms delay every second, your $30,000 hardware is effectively running at 90% capacity. You have paid for 100 GPUs but are getting the output of 90.

3.3 Tail Latency Compounding

Most performance discussions focus on average latency. Real systems fail in the tail.

Recompute doesn’t slow everything down evenly. It creates latency cliffs:

one request returns instantly,

the next takes tens of seconds,

the next times out entirely.

In multi-turn systems, this is especially damaging. A delay early in a sequence compounds across every subsequent step. A few hundred milliseconds of additional latency at each step can turn a task that should take seconds into something that takes minutes.

This is why time-to-first-token (TTFT) matters more than raw throughput for interactive systems. Users don’t notice peak tokens per second; they notice pauses.

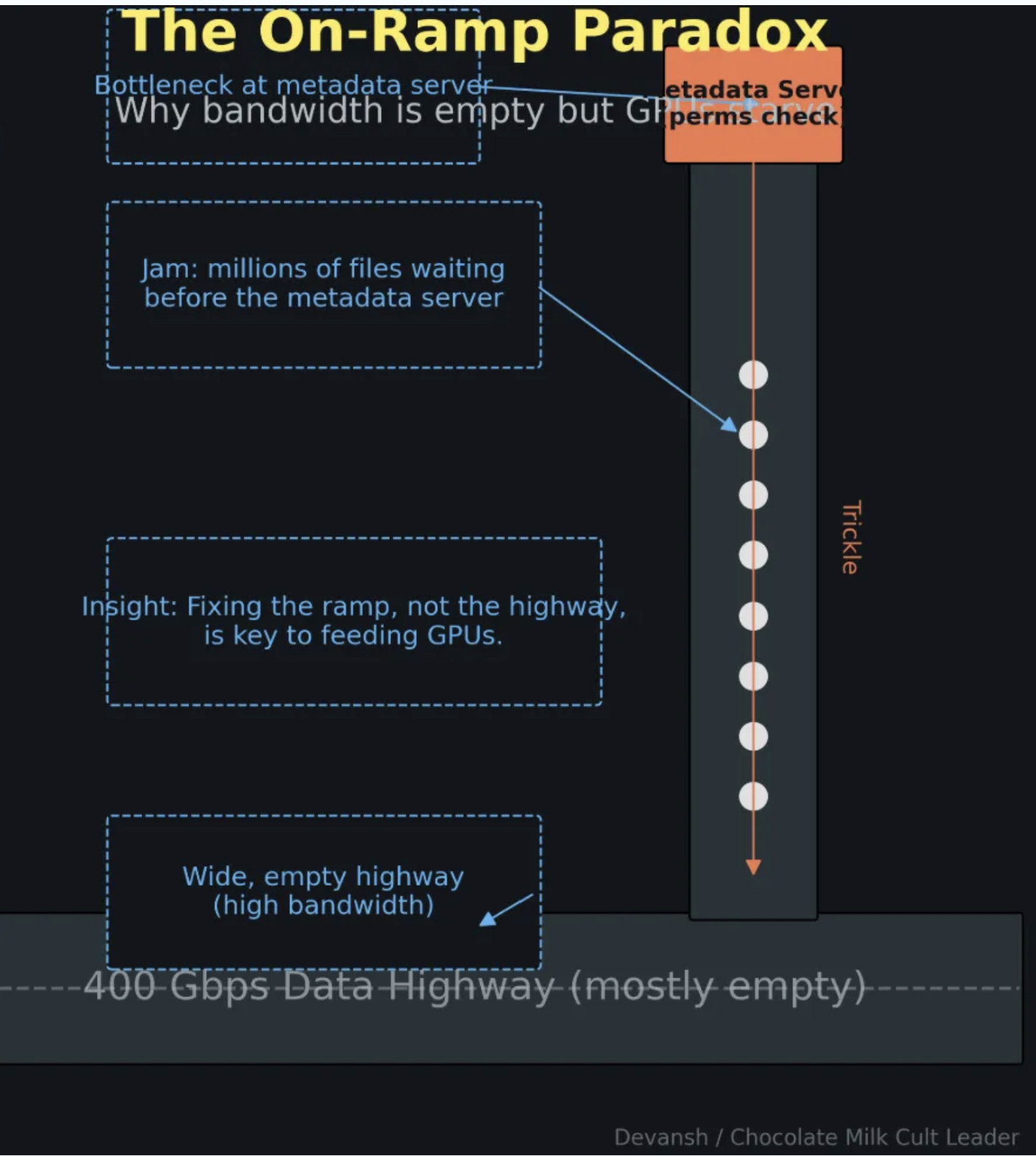

3.4 Metadata Storms

AI pipelines rarely deal with one 100TB file. They deal with ten million 10MB files (checkpoints, dataset shards, logs).

Every file on a storage system has data about the data, called metadata. This includes the file’s name, its size, its location, and permissions. While the data itself might be large, metadata operations are typically small, fast, and numerous.

Every time a GPU asks for a file, it hits the storage system’s Metadata Server. The server has to check permissions, look up the file location, and update the access time.

Unfortunately, when a 1,000-node training run starts, every node hits the server simultaneously. The bandwidth pipes are empty, but the server is deadlocked handling the index. The cluster sits idle, burning electricity, waiting for the filesystem to figure out where the data is.

(If your manager is smart, they will use this opportunity to get more budget and headcount, thereby increasing their “importance” to the organization. When you start looking into the stories, it’s crazy how many corporate incentives can be gamed to reward failure and punish efficiency).

The Requirements List

Any solution to these problems needs to:

Keep state without recompute: persistent, accessible KV cache that survives session migration and GPU memory pressure

Feed GPUs consistently: throughput that scales with cluster size without creating starvation

Handle metadata-heavy pipelines: no centralized chokepoint for file operations

Deliver predictable latency: low tail latency, not just low average latency

Scale without coordination bottlenecks: adding nodes should add capacity, not add contention

This is the checklist WEKA’s architecture is designed to satisfy. Let’s look at how.

4. What WEKA Is Actually Trying to Build

If you strip away the marketing gloss and the venture capital slide decks, Weka’s core thesis is deceptively simple: Storage is too slow because the software we use to talk to it was written for a world before CR7 went on his generational run; a world before butt-scooters and guard pullers ruined grappling.

So what do you do for our brave new world? According to Weka, you build a distributed data plane that behaves like a new memory tier at cluster scale.

We’re going to be getting into this.

What does this mean? And why? Let’s discuss that.

4.1 Why “Just Make Storage Faster” Doesn’t Work

The obvious solution to the problems in Section 3 is: make storage faster. Buy faster SSDs. Use faster networks. Problem solved.

This misses the point. Modern NVMe drives are already fast — 14 GB/s per drive is achievable. The bottleneck isn’t the media. It’s everything between the media and the GPU.

When a GPU requests data through a traditional storage stack, here’s what happens:

The request goes through the application

Into the kernel’s filesystem layer

Through the block device layer

Out the network stack (TCP/IP)

Across the wire to the storage server

Into that server’s kernel

Down to the drive

Then the whole path reverses

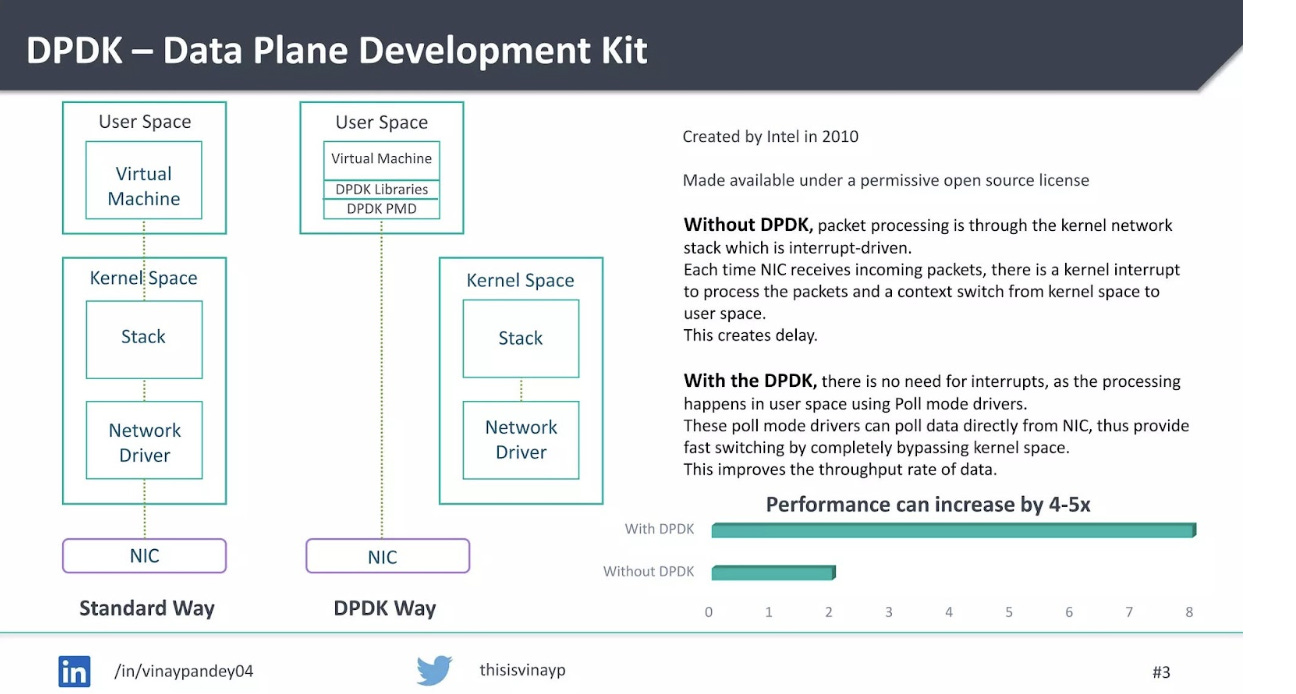

Each layer adds latency. Each transition involves a context switch. Each context switch involves the CPU. The CPU becomes the bottleneck — not because it’s slow, but because it’s doing bureaucratic work instead of useful work.

4.2 The Four Barriers

Traditional storage systems are hit a 4-piece that they haven’t really solved:

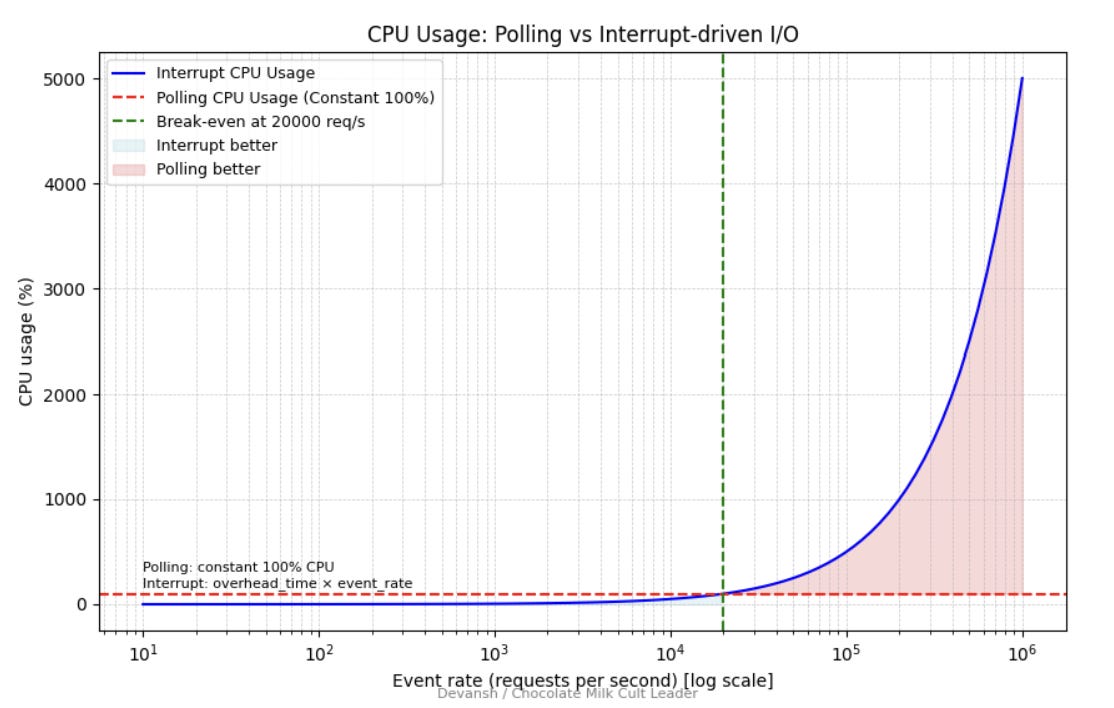

Software overhead: Every I/O operation going through the Linux kernel pays a tax. Context switches, interrupt handling, memory copies. Microseconds each, but they add up to milliseconds at scale.

Unpredictable latency: Garbage collection, lock contention, TCP retransmits. Traditional stacks have too many sources of jitter. For AI workloads, jitter is often worse than raw slowness.

CPU involvement: The CPU has to touch every I/O operation in traditional stacks. At high throughput, the CPU becomes saturated before the network or storage does. You’re bottlenecked by the least scalable component.

Coordination at scale: Centralized metadata servers. Lock managers. Consistency protocols. These were designed for correctness, not for thousands of parallel readers hitting the same namespace.

These aren’t hardware problems as much as they’re architecture problems. You can’t buy your way out of them. You have to build differently.

And that is where Weka comes in.

4.3 Two Components Powering Weka

WEKA’s answer comes in two parts:

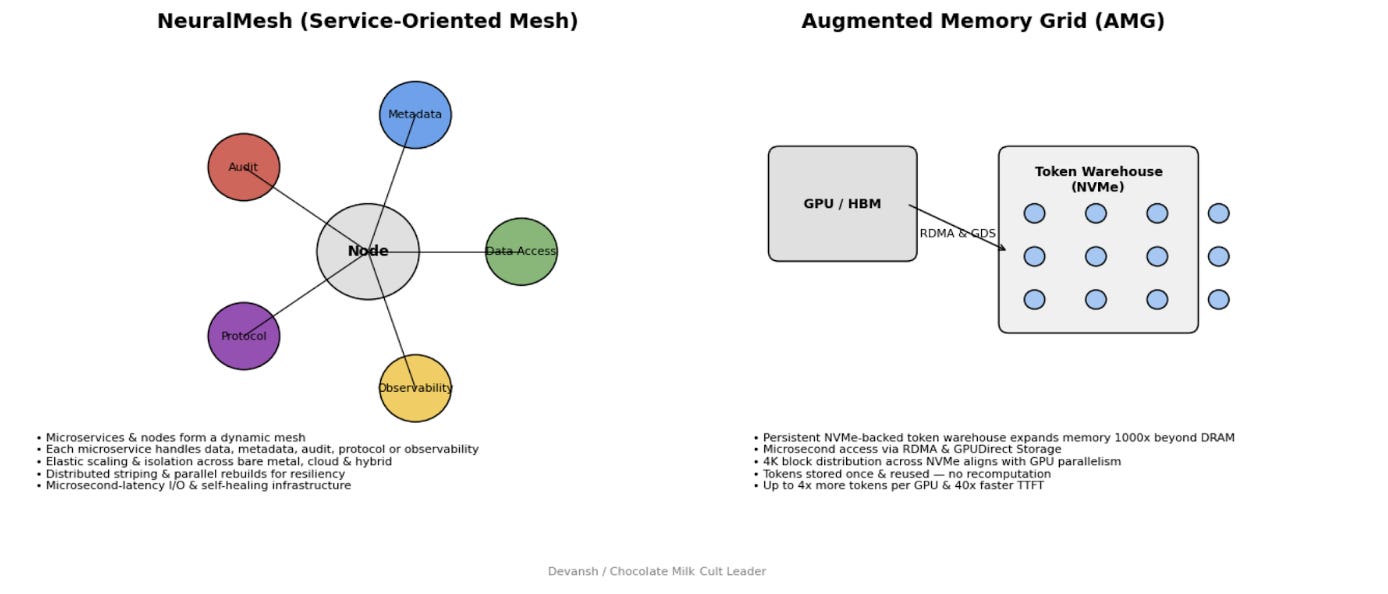

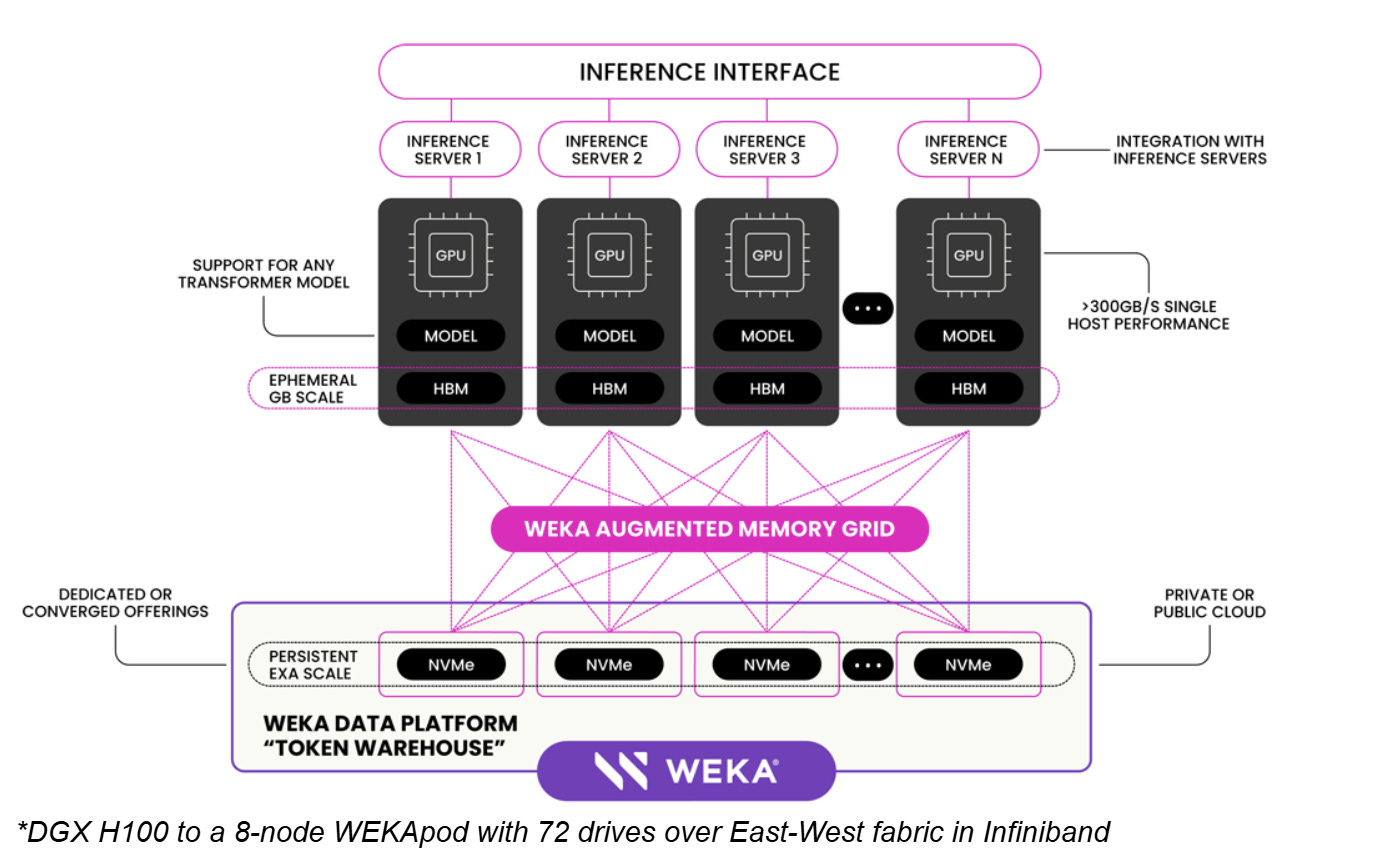

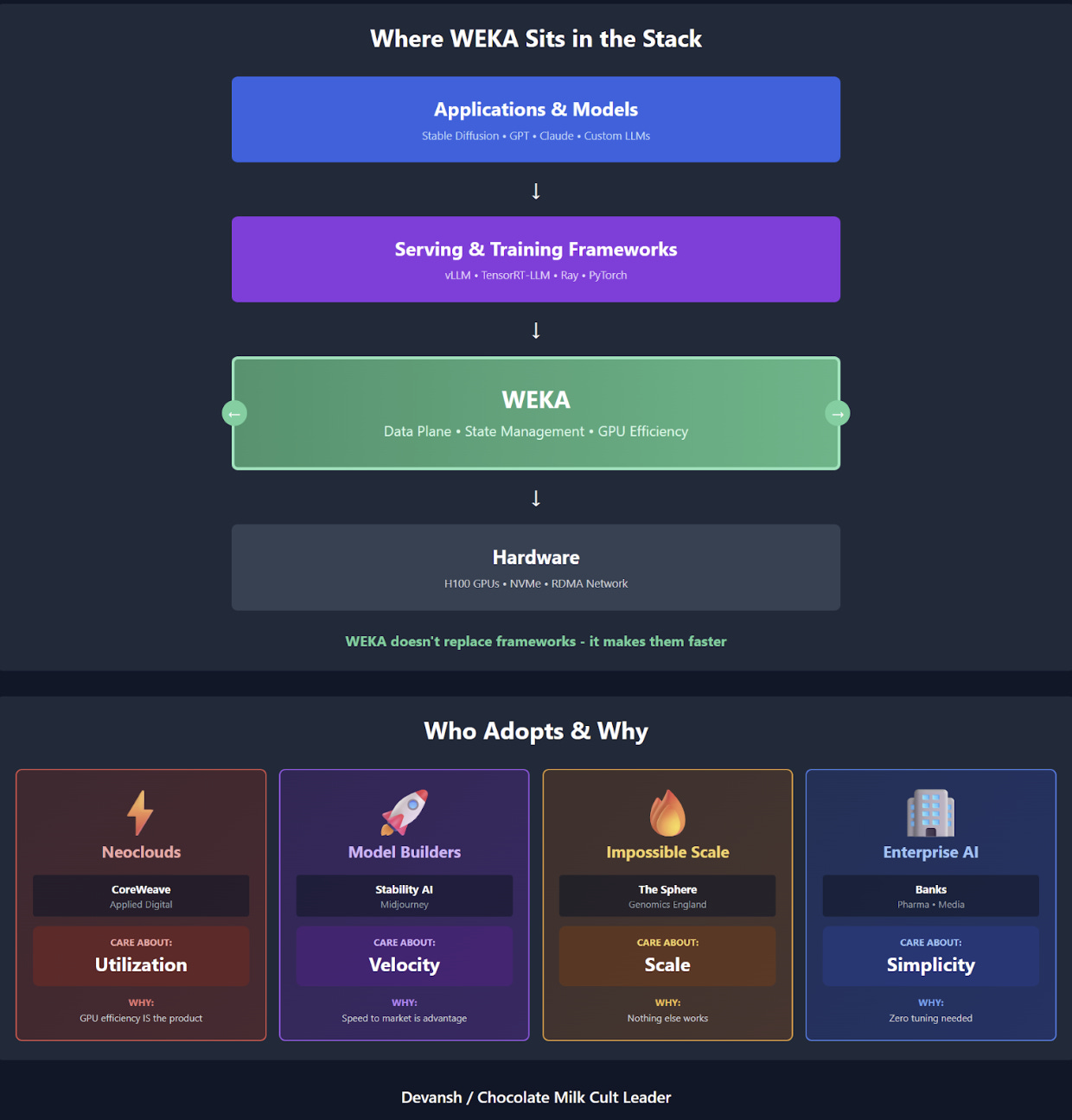

NeuralMesh is the foundation. It’s a distributed, NVMe-native data plane that bypasses the kernel, distributes metadata, and scales linearly with nodes. This is what makes WEKA “fast storage.”

Augmented Memory Grid (AMG) is the wedge into AI specifically. It takes NeuralMesh’s speed and uses it to externalize GPU working memory — KV cache — into shared, persistent storage that’s fast enough to feel like another memory tier.

NeuralMesh solves the data plane problem: feeding GPUs without starvation or coordination bottlenecks. AMG solves the state problem: keeping KV cache alive without the recompute tax.

Together, they’re targeting a new position in the infrastructure stack — not “where you store files” but “where working state lives when it doesn’t fit in memory.”

So far, all the foreplay, all of this setup, has been leading up to this. Some of you ChatGPT warriors are probably tuckering out by now, but don’t go blow everything and go soft on me now. Weka’s solutions deserve a lot of love, so let’s take them one at a time.

“The design philosophy behind NeuralMesh was to create a single storage architecture that runs on-premises or in the public cloud with the performance of all-flash arrays, the simplicity and feature set of Network-Attached Storage (NAS), and the scalability and economics of the cloud in a single unified system” — Their NM whitepaper.

5. NeuralMesh Deep Dive

NeuralMesh is a distributed, NVMe-native data plane for high-parallel workloads. Not a filesystem first — a data plane. The filesystem semantics (files, directories, permissions) sit on top. But the core innovation is underneath: how data actually moves.

5.1 The Default I/O Path (And Why It’s Slow)

We covered the high-level path in Section 4. Let’s get specific about where the time goes.

When an application reads data through the standard Linux storage stack:

System call: Application calls read(). This triggers a transition from user space to kernel space. Cost: ~1–2 microseconds.

VFS layer: The Virtual File System figures out which actual filesystem handles this request. More function calls, more overhead.

Filesystem layer: ext4, XFS, whatever. Translates the logical read into block operations. May involve journal checks, inode lookups, extent tree traversals.

Block layer: Queues the I/O, maybe does some merging or scheduling. More overhead.

Device driver: Finally talks to the actual hardware.

Interrupt handling: When the I/O completes, the hardware fires an interrupt. The CPU stops whatever it was doing, saves state, handles the interrupt, restores state. Cost: ~5–10 microseconds per interrupt.

Data copying: The data typically gets copied from the device into kernel buffers, then copied again from kernel buffers into application memory. Each copy costs memory bandwidth and CPU cycles.

Now multiply this by millions of I/O operations. Those microseconds become seconds. Those CPU cycles become saturated cores.

The irony: NVMe drives can complete a read in ~10 microseconds. But by the time you’ve paid the software tax, you’re at 100+ microseconds. The storage is fast. The path to it is slow.

5.2 Kernel Bypass WEKA’s Escape Route

WEKA’s core architectural move is simple in concept, difficult in execution: don’t use the kernel for I/O.

The WEKA software runs in user space, inside Linux containers. But inside those containers, it runs its own Real-Time Operating System (RTOS). It carves out dedicated CPU cores that the Linux kernel doesn’t touch. It talks directly to NVMe drives and network cards without going through Linux’s device drivers.

This is called kernel bypass, and it changes the economics of I/O completely.

How it works:

DPDK (Data Plane Development Kit): WEKA uses DPDK to bypass the kernel’s networking stack entirely. Packets go directly from the network card to WEKA’s user-space code. No interrupts. No kernel involvement. No copies into kernel buffers.

Dedicated cores: WEKA pins specific CPU cores to I/O processing. These cores poll for new work continuously instead of waiting for interrupts. Polling sounds wasteful, but it eliminates interrupt overhead entirely. At high I/O rates, this is a net win.

Zero-copy data paths: Data moves from NVMe to network wire (or vice versa) without being copied through intermediate buffers. The CPU orchestrates the transfer but doesn’t touch the actual bytes.

Stack these together and latency drops from 100+ microseconds to single-digit microseconds. More importantly, latency becomes consistent. No garbage collection pauses. No lock contention. No interrupt storms. The jitter that kills tail latency in traditional systems mostly disappears.

This has some pretty cool outcomes. Remember GPU starvation from Section 3? GPUs sitting idle because data can’t arrive fast enough?

Stability AI reported 93% GPU utilization after moving to WEKA. Before that, their clusters were frequently starved. Let’s do rough math on what that’s worth:

100 H100 GPUs at $2.50/hour = $250/hour

Utilization improvement from 75% to 93% = 18 percentage points

Value of recovered utilization: $250 × 0.18 = $45/hour = $32,400/month

That’s not counting the 35% reduction in training time they also reported. Faster training means faster iteration means faster time-to-market. Hard to put a number on that, but it’s not zero.

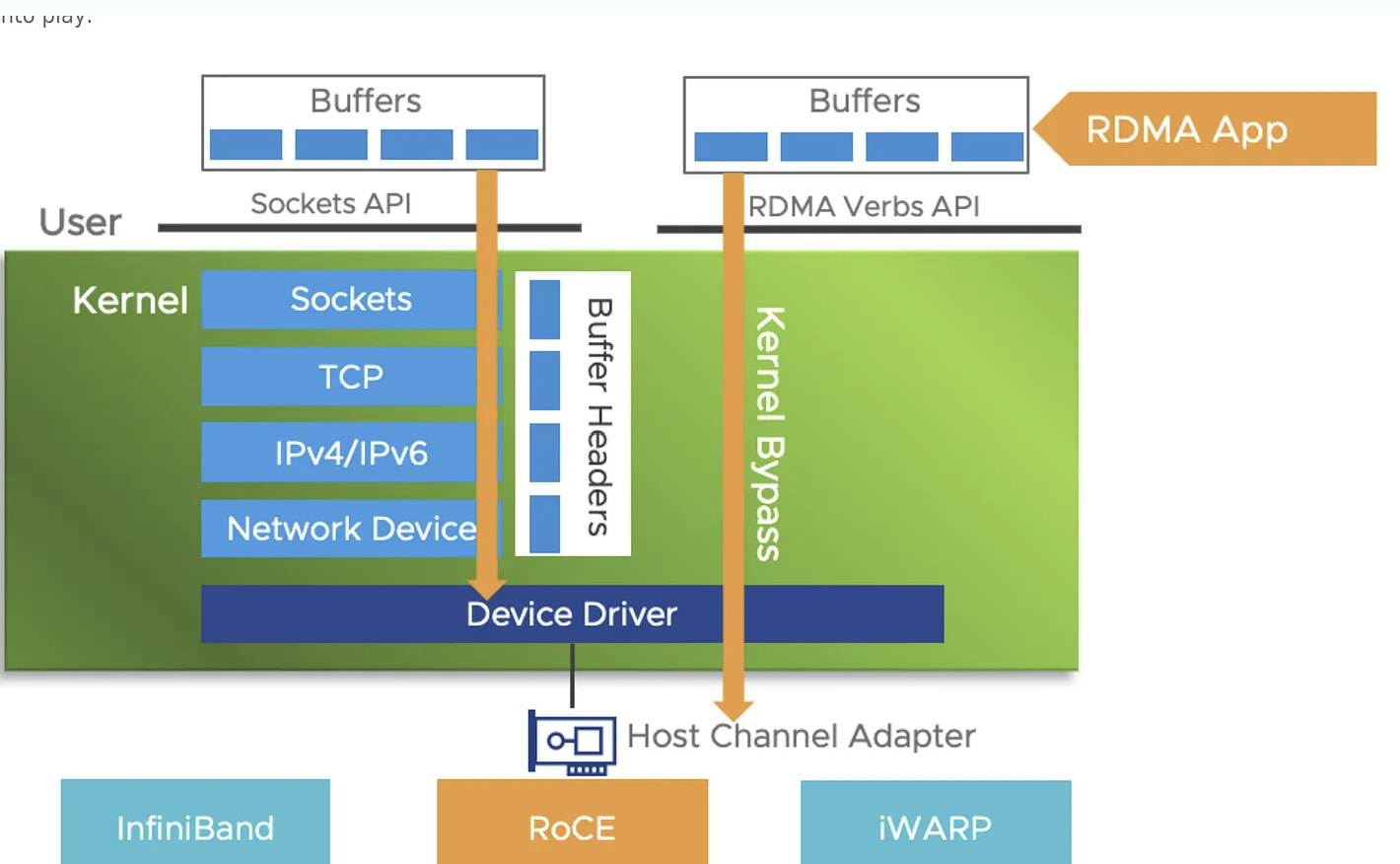

5.3 RDMA: The Network That Doesn’t Need the CPU

Fast storage is useless if the network can’t keep up. And traditional TCP/IP networking has the same problems as traditional storage: too much kernel involvement, too much copying, too much CPU overhead.

WEKA uses RDMA (Remote Direct Memory Access). In plain terms: one machine can read from or write to another machine’s memory without either CPU being involved in the data transfer.

The CPU sets up the transfer: “read these bytes from that address on that machine, put them here.” Then the network hardware does the actual work. The CPU is free to do other things.

Why this matters:

In a traditional TCP/IP stack, the CPU has to:

Fragment data into packets

Add headers

Compute checksums

Handle acknowledgments

Reassemble packets on the other end

Copy data between buffers at each stage

With RDMA, the network card handles all of this. The CPU just says “go” and gets notified when it’s done. Thus, throughput scales with cluster size without the CPU becoming the bottleneck. You can saturate 400GbE links (~50 GB/s per link) without burning all your CPU cores on network processing.

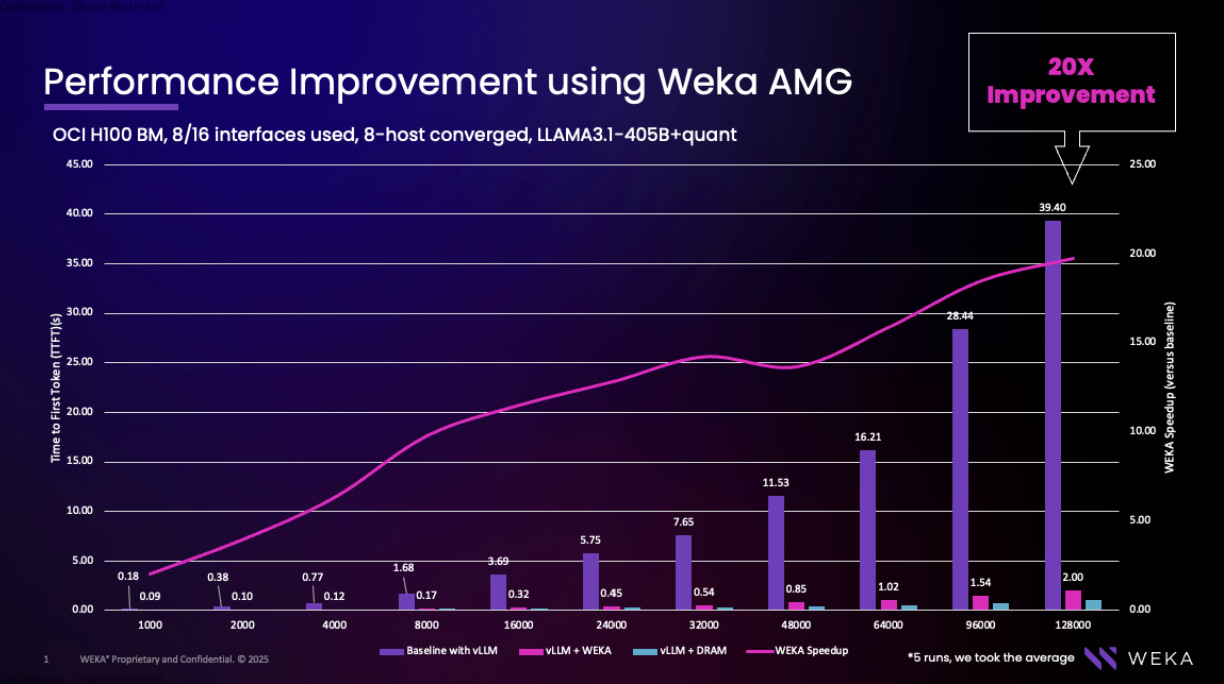

WEKA showed 269 GiB/s aggregate throughput across an 8-node H100 cluster. That’s not theoretical peak — that’s measured, sustained throughput. Try getting that with TCP/IP and watch your CPUs melt.

5.4 The Metadata Problem

Now we get to the part that separates serious distributed storage from toys.

Data operations (read bytes, write bytes) are relatively easy to parallelize. You stripe data across many drives, and reads/writes can happen in parallel. More drives = more throughput. Simple.

Unfortunately, metadata operations are hard.

Every file has metadata: name, size, location, permissions, timestamps. Every directory is essentially a metadata structure. When you ls a directory, that’s a metadata operation. When you open() a file, metadata. When you stat() to check if a file exists, metadata.

In traditional parallel filesystems (Lustre, GPFS), metadata lives on dedicated servers called MDS (Metadata Servers). Every metadata operation goes to the MDS. The MDS is the source of truth.

The problem?

When 1,000 nodes start a training job simultaneously, every node needs to open its shard of the dataset. Every open is a metadata operation. All 1,000 nodes hit the MDS at once.

The MDS becomes a traffic cop at a broken intersection. Doesn’t matter how fast your drives are or how fat your network pipes are — you’re serialized on one server’s ability to handle metadata lookups.

This is why “time to first batch” can be minutes even when the actual data transfer would take seconds. The cluster is waiting for the filesystem to answer the question “where is this file?” a million times.

“One of the standout achievements for WEKA was its metadata performance, reaching 1,753.69 kIOP/s, nearly 2x higher than Lustre’s 895.35 kIOP/s. This makes WEKA an ideal solution for workloads that require heavy metadata operations, such as AI/ML model training, large-scale simulations, and genomic research.

WEKA’s easy stat performance hit 15,370.21 kIOP/s, dwarfing Lustre’s 1,739.90 kIOP/s. “

— IO500 Benchmark. That’s 3–5x better metadata performance per node. Not because WEKA has faster CPUs, but because the architecture doesn’t have a central bottleneck.

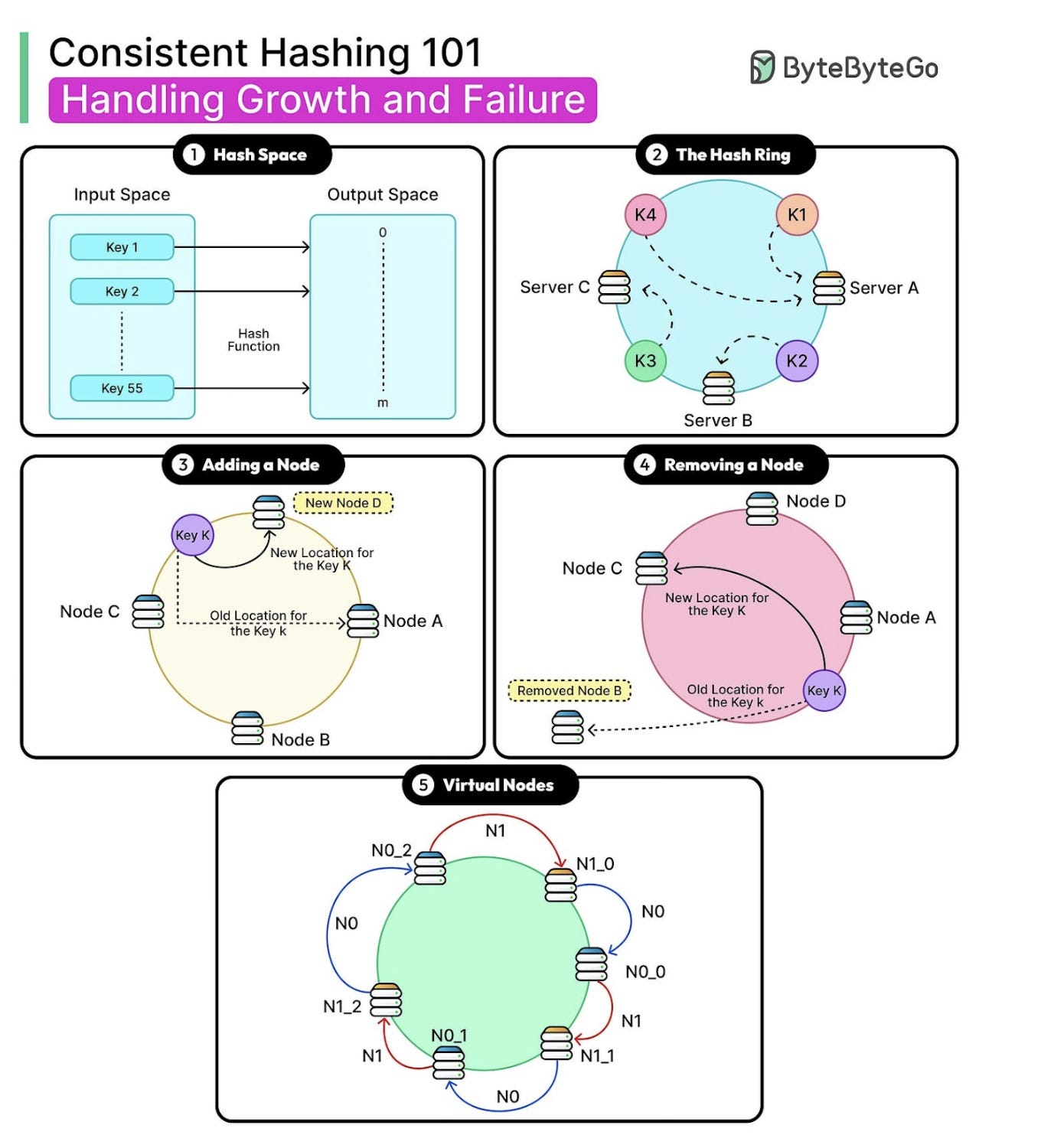

5.5 Distributed Hashing: Metadata Without a Middleman

WEKA’s solution is elegant: eliminate the dedicated metadata server entirely.

Instead, metadata is distributed across all nodes in the cluster using consistent hashing. When you need to find a file’s metadata, you don’t ask a central server. You compute a hash of the file identifier, and the hash tells you which node owns that metadata.

Here’s how it works:

Every file has an identifier (inode number, essentially)

Run the identifier through a hash function

The hash output maps to a specific node in the cluster

That node owns the metadata for that file

Go directly to that node — no central lookup required

This comes with a few benefits:

No hotspots: Metadata is evenly distributed. No single node gets hammered while others sit idle.

Linear scaling: Add more nodes, get more metadata capacity. The math works out: 10 nodes can handle 10x the metadata operations of 1 node.

Parallel operations: Different files hash to different nodes. Thousands of simultaneous metadata operations can happen in parallel, on different nodes, with no contention.

No single point of failure: If one node dies, only the metadata it owned is temporarily unavailable (and that gets rebuilt fast — more on this shortly).

WEKA claims “billions of files in a single directory without performance degradation.” This is a wild number, but not implausible when you think about the architecture. In a hash-distributed system, directory size doesn’t create hotspots because the contents of the directory are spread across all nodes. There’s no single server that has to handle “list this billion-file directory.”

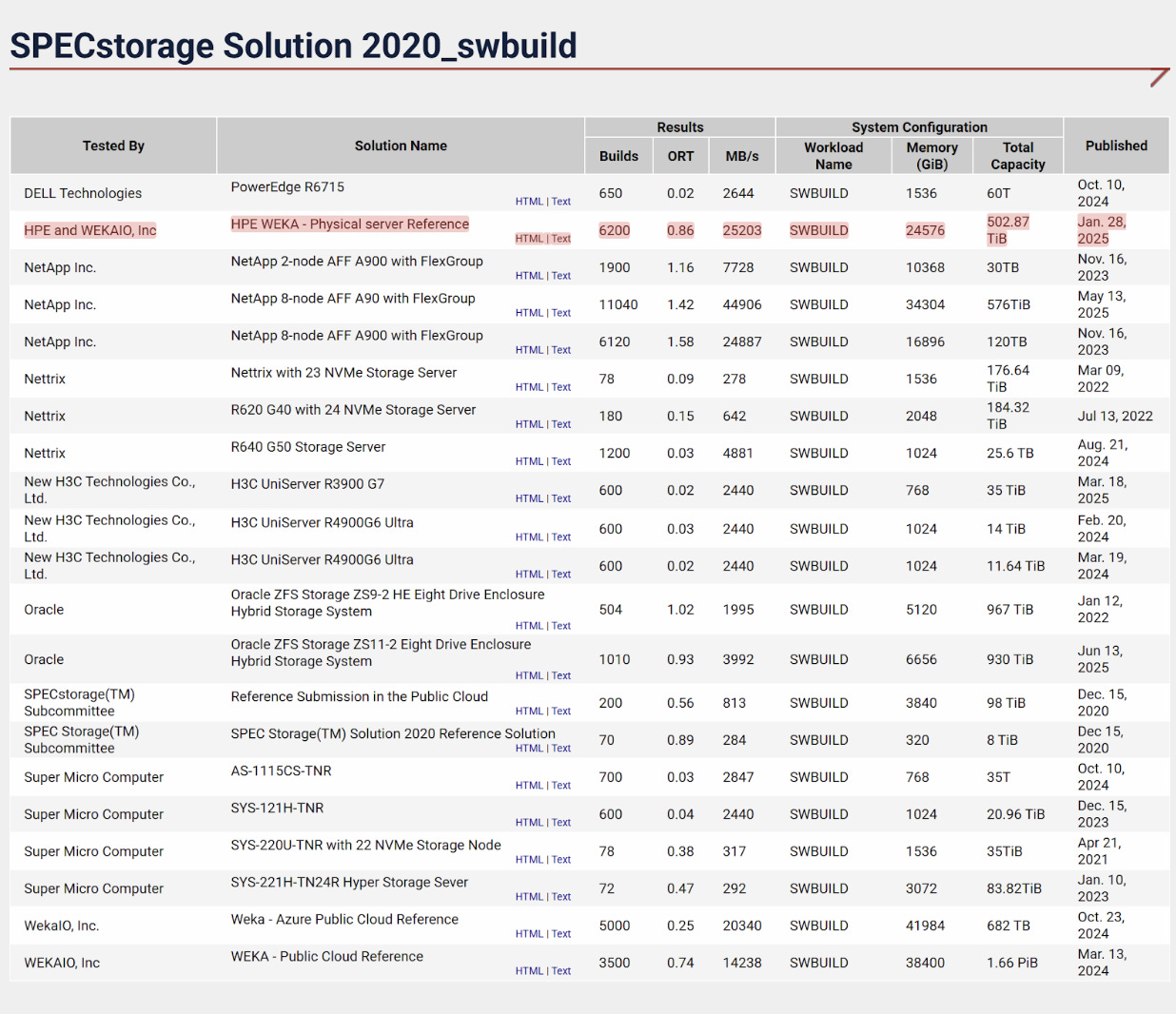

The SPECstorage SWBUILD benchmark specifically tests metadata-heavy workloads (software compilation = tons of small files, constant open/close/stat operations). WEKA scored 6,200 builds — one of the highest there —

5.6 Resiliency: The Hidden Performance Feature

Storage systems fail. Drives die. Nodes crash. Timmy spills his drink on a major compute cluster. The question is what happens next.

Traditional approach: dedicated hot spares. You buy extra drives that sit idle, waiting for a failure. When a drive dies, the system rebuilds onto the spare.

Problems:

Idle hardware is wasted money

Rebuild happens on one drive, so it’s slow

During rebuild, you’re vulnerable — another failure could mean data loss

Rebuild I/O competes with production I/O, degrading performance

WEKA’s approach: virtual hot spare + parallel rebuild.

Instead of dedicated spare drives, WEKA reserves capacity across all drives. When a drive fails:

Every surviving drive participates in the rebuild

Data is reconstructed in parallel across the entire cluster

Rebuild time drops from hours to minutes. Huge b/c the data can be lost during rebuilds, and thus lower rebuild time → better security.

The “rebuild penalty” on performance is distributed, not concentrated

This means WEKA can tolerate 2 or 4 simultaneous failures (depending on configuration) without data loss. The data is erasure-coded and striped across “failure domains” that can be drives, nodes, racks, or even availability zones. This also plays into some good business outcomes:

Lower Downtime saves money.

Better performance saves money that would be otherwise lost to degraded systems.

The Ops teams can be a bit more aggressive, ensuring higher possible upside.

(It’s why some organizations justify higher upfront storage costs: the operational overhead of babysitting fragile systems has real cost, even if it doesn’t show up on the hardware invoice.)

5.7 What This Unlocks

Everything we’ve covered in this section — kernel bypass, RDMA networking, distributed metadata, parallel rebuild — is about making the data plane fast, consistent, and scalable.

But NeuralMesh is still “just” fast storage. The next section is where it gets interesting: using that fast storage as an extension of GPU memory.

That’s where AMG comes in.

6. Understanding Weka’s Augmented Memory Grid

Everything we’ve covered so far — kernel bypass, RDMA, distributed metadata — was about building a faster data plane. NeuralMesh is the highway. But a highway is only useful if you have vehicles designed to drive on it.

AMG is that vehicle. It takes the speed NeuralMesh provides and weaponizes it for one specific purpose: making GPU working memory overflow to storage instead of disappearing.

6.1 Why KV Cache Overflows

Let’s get specific about the math that breaks GPU memory.

When an LLM processes your prompt, it builds the KV cache — tensors representing the relationships between tokens. The cache size scales with model architecture and context length:

KV cache ≈ 2 × num_layers × num_heads × head_dim × context_length × bytes_per_element

For Llama 70B with a 128k context window at FP16 precision:

2 × 80 layers × 64 heads × 128 dim × 128,000 tokens × 2 bytes ≈ 20GB

One user. One conversation. 20GB.

An H100 has 80GB of HBM. The model weights for a 70B parameter model take ~140GB (you’re already tensor-parallel across multiple GPUs just to load it). What’s left for KV cache is a fraction of that 80GB per chip.

You can fit maybe 3–4 concurrent long-context sessions before memory fills. Now scale to a real service: thousands of users, many with long contexts, some returning hours later still expecting continuity. When HBM fills, you have three options:

Crash — OOM. Obviously bad.

Evict — delete old KV caches. User returns, their context is gone, you recompute, paying the tax we mentioned earlier.

Limit — refuse long contexts or cap concurrency. Bad for a space as competitive and cutthroat as AI.

What if you could move KV caches to storage when HBM fills, then pull them back when needed — fast enough that it feels like memory, not like file I/O? This is the idea that AMG tries to bring in.

6.2 GPUDirect Storage: The Last Mile

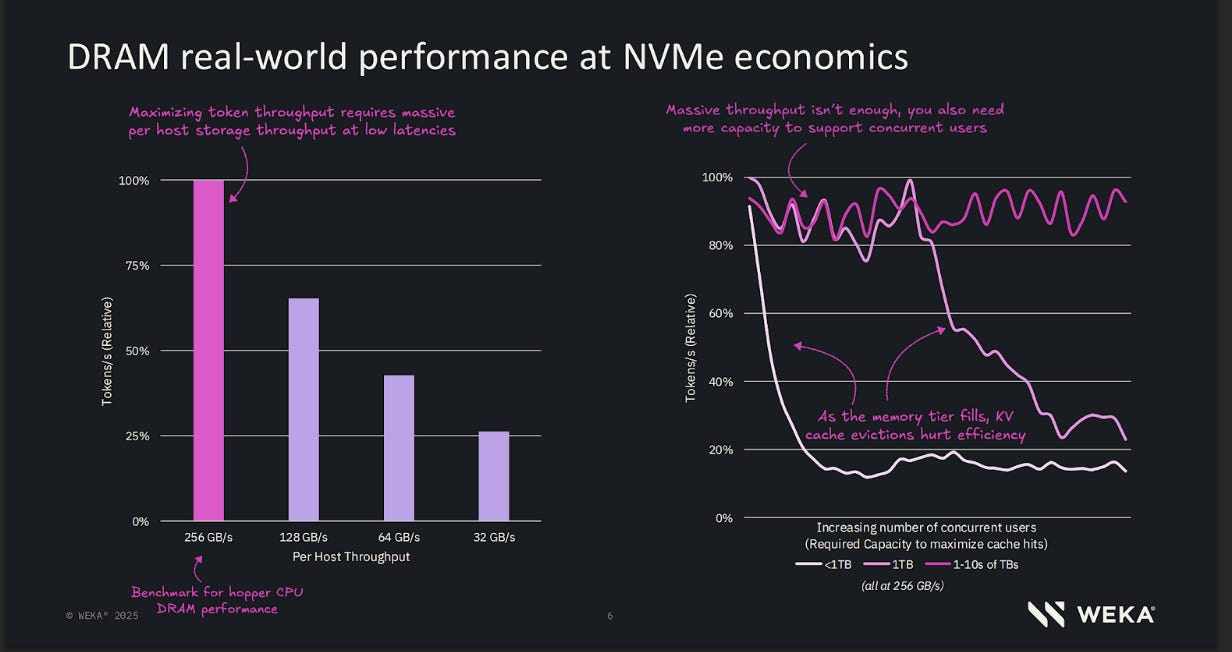

Section 5 covered how NeuralMesh makes the data plane fast — kernel bypass, RDMA, and distributed metadata. But there’s a gap that section didn’t address: even with RDMA moving data at line rate between nodes, the data still lands in CPU memory first. Getting it into GPU HBM requires another copy.

For KV cache retrieval, that’s the wrong destination. The cache needs to end up in GPU memory, not system RAM. An extra copy through DRAM adds latency and burns CPU cycles.

GPUDirect Storage (GDS) closes that gap.

GDS allows storage devices to DMA directly into GPU memory. The path becomes:

Remote NVMe (Node B) → RDMA → Node A’s NIC → PCIe switch → Node A’s GPU HBM

No staging in system RAM. No CPU memcpy. The CPU sets up the transfer, but the actual bytes flow through PCIe directly to the GPU. This works because modern NICs and GPUs sit on the same PCIe switch and can address each other’s memory directly.

WEKA’s OCI testing showed a single H100 node pulling 192 GiB/s reads via GDS. Aggregate across multiple nodes and NVMe devices, and you hit the ~300 GB/s figures WEKA cites for AMG.

For context, HBM runs at ~3 TB/s but gives you 80GB and vanishes when power cuts. System DRAM runs at ~100 GB/s, gives you 512GB to 2TB, also volatile. AMG over networked NVMe hits 40–340 GB/s, scales to petabytes, and persists.

That last number is the trick. 40–340 GB/s from networked storage is within striking distance of local DRAM bandwidth. Not as fast as HBM — nothing is — but fast enough that retrieving cached state is radically cheaper than recomputing it.

(However, a critical distinction must be made regarding where this traffic flows. Traditional storage relies on ‘North-South’ traffic — data entering from external storage networks, traversing switches, and fighting for bandwidth.

WEKA achieves its performance by utilizing the East-West compute fabric (InfiniBand or Ethernet rails usually reserved for GPU-to-GPU communication). By pinning reads to the NIC closest to the GPU (PCIe locality) and riding the compute rail, WEKA minimizes the physical distance. The ‘single-digit microsecond’ latency refers to WEKA’s internal software processing; the total end-to-end latency is higher but remains indistinguishable from local media because it bypasses the standard storage network bottlenecks.)

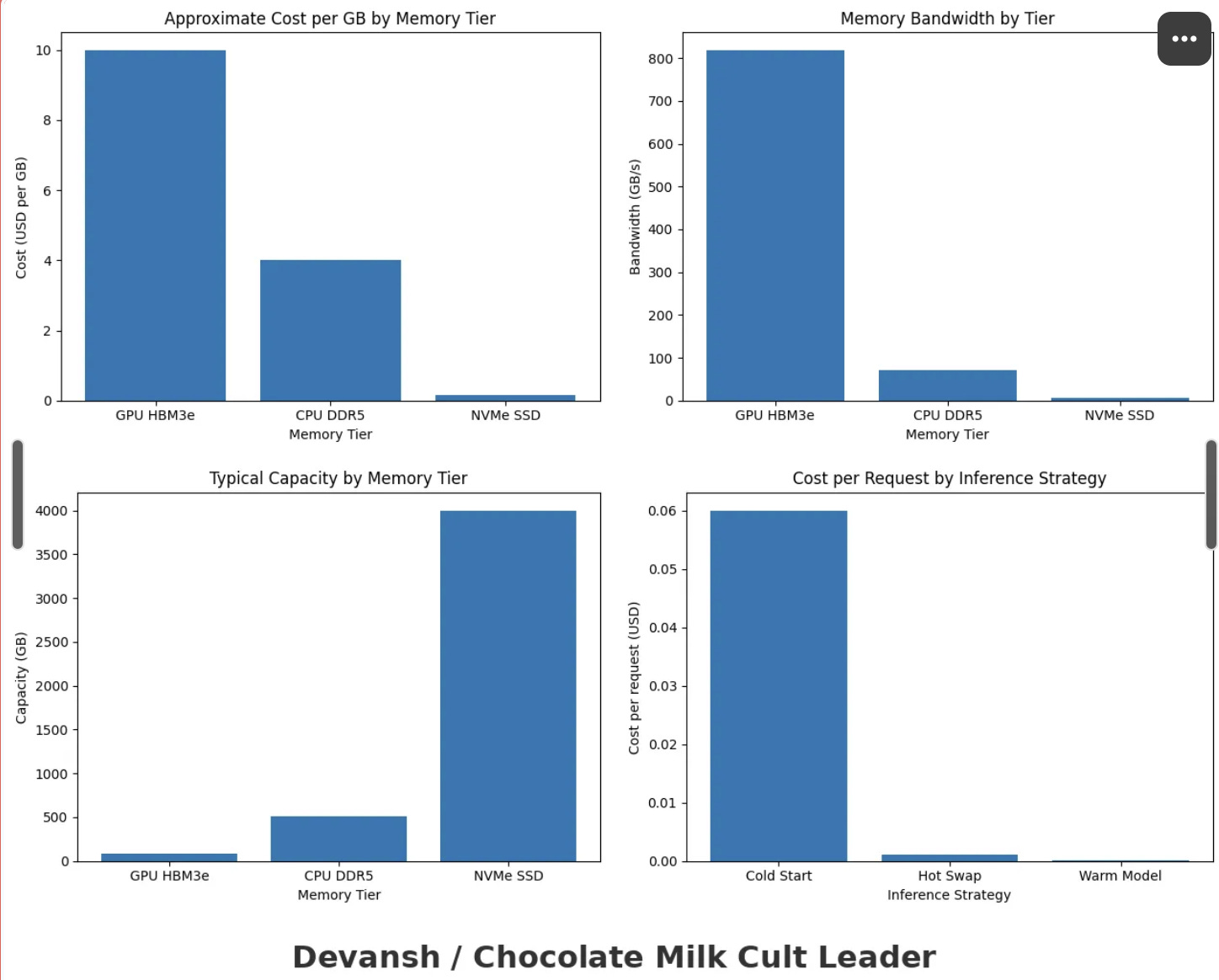

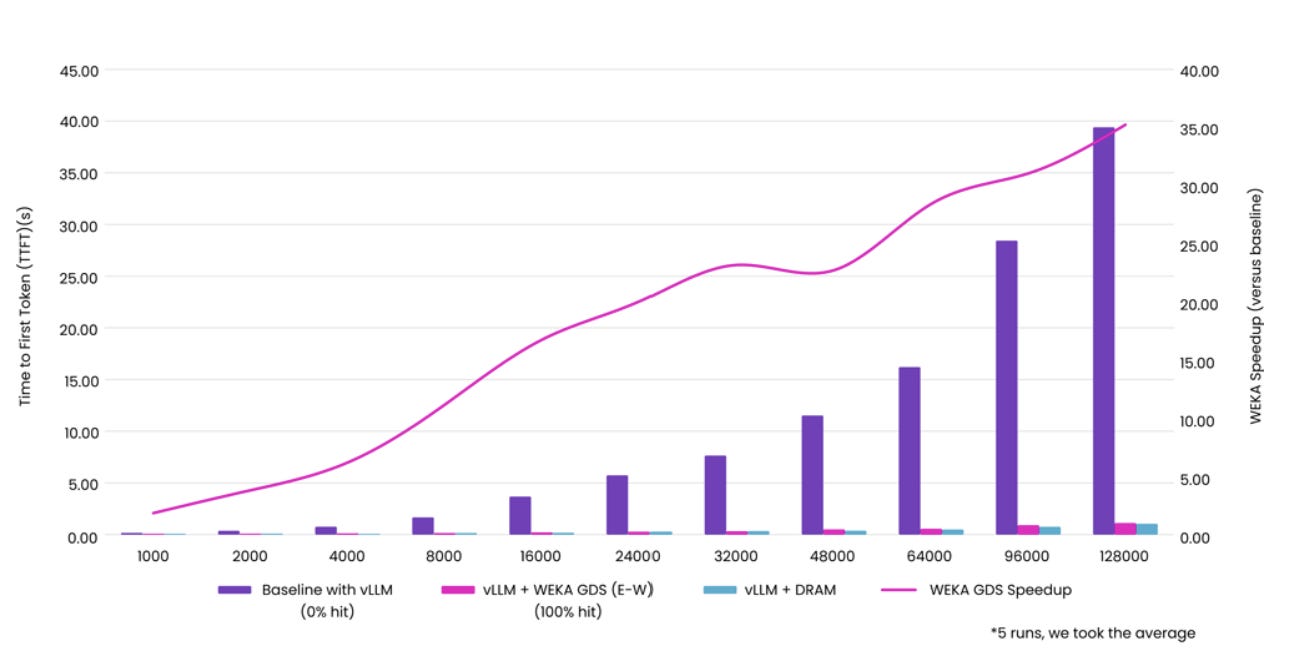

When looking at OCI’s H100 testing, 128k token context, Llama 70B:

Configuration Prefill Latency vLLM baseline (no persistent cache) 39.4 seconds

vLLM + WEKA AMG 2.0 seconds

That’s 19.7x faster. Reading data is faster than computing it. This sounds obvious, but traditional storage stacks made retrieval slow enough that recompute was often competitive. GDS changes that math.

Looking at the costing, at $2.50/hour per H100, 37 seconds of GPU time costs ~$0.026.

Sounds small until you scale it:

1,000 follow-up requests per day

30% would have triggered recompute (cache miss under traditional eviction)

300 requests × $0.026 = $7.80/day per GPU

10-GPU cluster: $78/day = $2,340/month in recovered GPU time

And that’s just direct compute savings. The second-order effect is what happens to throughput, user satisfaction, and other goodies.

6.3 State Disaggregation: The Architectural Unlock

In traditional inference deployments, state is married to hardware. If User A’s session started on GPU-05, their KV cache lives in GPU-05’s memory. Every subsequent request from User A must route to GPU-05, or you lose the cache and recompute.

This is called session pinning, and it creates problems:

Fragmentation: GPU-05 is 90% utilized. GPU-06 is idle. But GPU-05 is holding User A’s cache, so their requests can’t migrate. The idle GPU can’t help.

Hotspots: Popular users (or users with long contexts) pin GPUs. Other users queue behind them.

Failure brittleness: GPU-05 crashes? User A’s session is gone. Recompute everything when they return.

Scaling friction: Spin up new GPUs and they can’t help existing sessions — the caches are pinned elsewhere.

AMG breaks session pinning.

The KV cache doesn’t live on GPU-05 anymore. It lives in the shared WEKA pool — persistent, accessible from any node in the cluster.

The new flow:

User A sends initial prompt → routed to GPU-05

GPU-05 does prefill, builds KV cache, writes it to AMG

GPU-05 generates a response

User A sends follow-up → GPU-05 is busy

Load balancer routes to GPU-06

GPU-06 fetches User A’s KV cache from AMG (via GDS, sub-second)

GPU-06 continues the conversation — no recompute

The user never knows a switch happened, and you contribute lesser to your cloud providers’ yacht parties.

It is worth taking a second to breathe here. AMG is orders of magnitude slower than HBM. Doesn’t matter. It’s fast enough not to disrupt user experience. Rory Sutherland has a bit about this — it’s billions to shave 20 minutes off a journey; cheaper to ensure connectivity throughout the journey. Many people would happily accept the Wifi trains and not complain about the transit if they had the latter.

There is often an instinct to always maximize the metric you can measure. But users accept “good enough” on performance if you give them convenience they didn’t know they wanted. You don’t have to overdeliver on every dimension; people will accept good enough if you make it convenient. The goal should be to identify all the areas where you can cut corners and only deliver the bare minimum there. Works for my relationships, and it certainly works in business.

Getting back to our Weka deep-dive, AMG creates a very interesting paradigm: it is stateless compute with stateful memory. The GPUs become interchangeable workers drawing from a shared memory pool. Sessions aren’t pinned to hardware; they’re pinned to the data plane. This unlocks a bunch of cool shit:

Elastic routing: Any GPU can serve any request. Load balancing becomes trivial.

Fault tolerance: GPU dies? Route to another. The cache survives in AMG.

True elasticity: Spin up GPUs and they immediately have access to all existing session state. No warmup, no migration.

Better utilization: No more idle GPUs holding caches they can’t release.

Getting into real numbers, CoreWeave’s testing with AMG showed 4.2x more tokens generated per GPU.

Without AMG, GPUs waste cycles on duplicate prefill (recompute tax) and can’t batch as aggressively (memory constraint). With AMG, KV caches overflow to storage instead of getting evicted, batch sizes grow, and GPUs spend their cycles on generation — the work that actually produces output.

From CoreWeave’s results: “Once DRAM’s cache capacity ceiling was surpassed, Augmented Memory Grid maintained KV cache hit rates, reduced TTFT by up to 6x and delivered up to 4.2x more tokens per GPU — all without additional hardware.”

If you can serve the same request volume with fewer GPUs:

Original fleet: 10 H100s at $2.50/hour = $18,000/month

With 4.2x efficiency: ~7 GPUs for same throughput = $12,600/month

Monthly savings: $5,400 from hardware reduction alone

Or flip it: same GPU count, 4.2x the revenue-generating capacity. For inference providers billing per token, that’s 4.2x the monetizable output from the same capital expenditure.

Once again, it is worth taking a second to put some nuance on these numbers. The ‘4.2x throughput’ multiplier is not magic; it is a function of the Cache Hit Rate. We can visualize this using the ‘Token Color’ framework:

Salmon Tokens (New Input): Require full prefill (matrix math). Compute-bound. Expensive.

Grey Tokens (Cached Input): Retrieved from memory/WEKA. Bandwidth-bound. Cheap.

Blue Tokens (Output): The generated response.

WEKA’s value proposition is converting expensive ‘Salmon’ work into cheap ‘Grey’ retrieval. If your workload is random, single-turn queries (0% cache hit rate), WEKA provides no throughput gain. The 4.2x efficiency is realized only in Agentic, Multi-turn, or Coding workflows where the context is reused, converting 90%+ of the input processing into memory lookups. Additionally, with a system like this, your choice of serving stack is another key variable, and must be optimized for to maximize the ROI you gain from this.

This is the “upside-down tokenomics” fix. Traditional inference economics punish long context because it consumes memory and triggers recompute. AMG inverts that — long context becomes a recoverable asset, not a liability that forces cache eviction.

6.4 The Capacity Expansion That Enables Multi-Agent Futures

The numbers that make this concrete:

HBM per H100: 80GB

Typical WEKA cluster: Petabytes

That’s a 10,000x+ expansion in addressable memory for AI working state. This matters because the systems being built aren’t single-turn chatbots. Agentic workloads accumulate state:

Multi-turn conversations: Context grows with each exchange

Tool-using agents: Each tool call adds to working memory

Agent swarms: Multiple sub-agents, each with their own context, coordinating through shared state

Long-horizon reasoning: Chain-of-thought that spans minutes, not seconds

A single agent coordinating a complex task might accumulate hundreds of thousands of tokens of context. A swarm of sub-agents multiplies that. None of this fits in HBM. All of it benefits from persistence — the ability to pause, resume, and continue without recompute.

AMG doesn’t make infinite context-free. But it makes the cost of holding context proportional to storage (cheap, scalable) rather than HBM (expensive, constrained).

WEKA’s internal testing showed 41x reduction in TTFT for 105k token inputs — 23.97 seconds down to 0.58 seconds. That’s the difference between “batch job” and “interactive agent.”

6.5 Where It Breaks: Limits and Failure Modes

AMG is not magic. It has edges, and you should know where they are before betting your tendies on it.

Network Congestion (The Physics of Shared Fabric): AMG’s performance depends entirely on network bandwidth being available. GDS and RDMA are fast, but they are still sharing the fabric with everything else in the cluster. Under heavy load — especially “incast” patterns where many GPUs request data simultaneously — you will see contention. The 300 GB/s aggregate throughput isn’t 300 GB/s when 50 GPUs are competing for it. WEKA’s distributed architecture mitigates hotspots, but the physics of shared bandwidth still apply.

SSD Endurance (The “Flash Burn” Risk): Treating NVMe SSDs like RAM creates a physical hardware risk. KV Cache is ephemeral and changes constantly. If you aggressively checkpoint state to disk every few seconds for thousands of concurrent agents, you risk exceeding the Drive Writes Per Day (DWPD) rating of the media (Write Amplification). Capacity planning must account for high-endurance Enterprise NVMe; if you use cheap, read-optimized QLC drives to save money, you will physically wear out the cluster’s storage media in months rather than years.

The “Noisy Neighbor” Effect: In a shared “AI Factory” environment, storage performance is zero-sum. If Tenant A is running a massive training run or aggressive cache demotions (thrashing the drives), Tenant B’s inference latency can spike. WEKA uses QoS and striping to mitigate this, but in high-load scenarios, tail latency (P99) often suffers before average throughput does. If you need guaranteed consistent latency for real-time agents, you may need to physically isolate the storage media, effectively breaking the “shared pool” economic benefit.

Capacity Planning & The “Eviction Cliff”: This is fast, but it is not infinite. You must size your NVMe capacity to hold the entire active working set of your agent fleet. The moment your working set exceeds the NVMe capacity, the system spills over to G4 (Object Storage/S3). When this happens, performance falls off a cliff — you drop from 300 GB/s to network speeds, and latency jumps from microseconds to milliseconds. This introduces “performance variance” that breaks user experience. You cannot under-provision this tier.

Demotion Overhead (The Traffic Jam): Moving data to storage (Demotion) is just as critical as retrieving it. In high-throughput scenarios, if the inference server (e.g., vLLM) cannot offload the KV cache to WEKA fast enough, the GPU HBM remains full, blocking new requests. The network bandwidth must support bidirectional traffic: reading cached states for active users while simultaneously writing evicted states for dormant users. If the “Demotion” path clogs, the entire system stalls.

The Cold Start Reality: AMG helps with returning users whose KV cache is already stored. It does not help with first requests — those still require full prefill (“Salmon Tokens”). If your workload is dominated by new, one-shot conversations (high user churn), AMG’s value diminishes. The ROI is strongest for multi-turn, long-context patterns — exactly the agentic workloads the market is moving toward.

What you’d want to test before production:

If I were evaluating AMG for a real deployment, I’d want to see:

Latency distributions under varying load (P50 is marketing; P99 is reality)

Behavior when NVMe tier hits 90%+ capacity

Performance degradation curve as working set exceeds hot tier

Multi-tenant isolation under adversarial traffic patterns

Recovery latency when nodes fail during active inference

SSD endurance projections under sustained write load

The published benchmarks are impressive, but they’re controlled conditions. Production is messier.

6.6 What AMG Actually Is

In human cognition, there’s a massive asymmetry between understanding and remembering. Reading a book takes hours. Recalling what it said takes seconds. Your brain doesn’t re-read the book every time you want to reference it.

Pre-AMG inference systems didn’t work this way. Every time context exceeded memory limits, the system forgot. Every time a user returned, the system re-read from scratch. The cost of remembering was the same as the cost of understanding.

AMG creates a memory tier where remembering is cheap. They have effectively rebranded this architectural layer as a ‘Token Warehouse.’

File Storage: Optimized for ‘Finished Goods’ (Datasets, Checkpoints).

Token Warehouse: Optimized for ‘Work in Progress’ (Active Context).

In an agentic workflow, the intermediate states of reasoning chains are too large for GPU memory but too valuable to discard. The Token Warehouse is the assembly line buffer for that Work-in-Progress.

The KV cache — the model’s “understanding” of your context — becomes a persistent asset rather than a disposable byproduct. It can be stored, retrieved, moved between GPUs, and reused. The work of understanding happens once; the benefit persists.

That’s the architectural bet. Not “faster storage” but “storage as memory.” Not “better caching” but “externalized GPU state.”

WEKA is wagering that as AI systems become more stateful — more agentic, more multi-turn, more persistent — the value of this memory tier compounds. Every system that wants to remember without recomputing becomes a potential customer.

The question isn’t whether the technology works. The benchmarks are clear. The question is whether the market moves toward workloads that need it.

Given everything happening in agents, long-context models, and multi-turn reasoning, that seems like a reasonable bet.

Section 7: Where WEKA Fits Today

Let’s zoom out. We’ve spent five sections on architecture and mechanisms. But technology doesn’t exist in a vacuum. Where does WEKA actually sit in the current AI infrastructure stack — not in some imagined future, but right now?

7.1 The “AI Factory” Reality

The assumptions of the cloud era — multi-tenancy, overprovisioning, “good enough” I/O — are dead. In an AI factory:

The Asset is the GPU: Everything else exists solely to keep the GPU busy.

The Workload is Stateful: It’s not just serving static web pages. It’s maintaining gigabytes of context per user.

Inference > Training: Self-explanatory

The Margin is Utilization: If your H100s run at 40% utilization because they’re waiting for data, you go bankrupt. If they run at 90%, we have a great time gambling in Monaco and Vegas.

7.2 WEKA’s Position

WEKA isn’t selling storage. They’re selling GPU efficiency. Nobody buying WEKA cares about $/TB or IOPS for their own sake. They care about:

Can I serve more users per GPU?

Can I reduce my recompute waste?

Can I hit latency SLAs on long-context workloads?

Can I stop babysitting fragile storage infrastructure?

WEKA’s pitch is: your GPUs are expensive and underutilized because your data plane is slow. Fix the data plane, and your existing GPUs become more valuable.

This is a fundamentally different sale than “we’re cheaper per terabyte” or “we have more features.” It’s: we make your most expensive asset work harder.

7.3 Who Cares Today and Why (The Adoption Patterns)

The early adopters of this architecture are not random. They fall into 4 distinct archetypes, each of whom feels the pain of the broken logistics system most acutely.

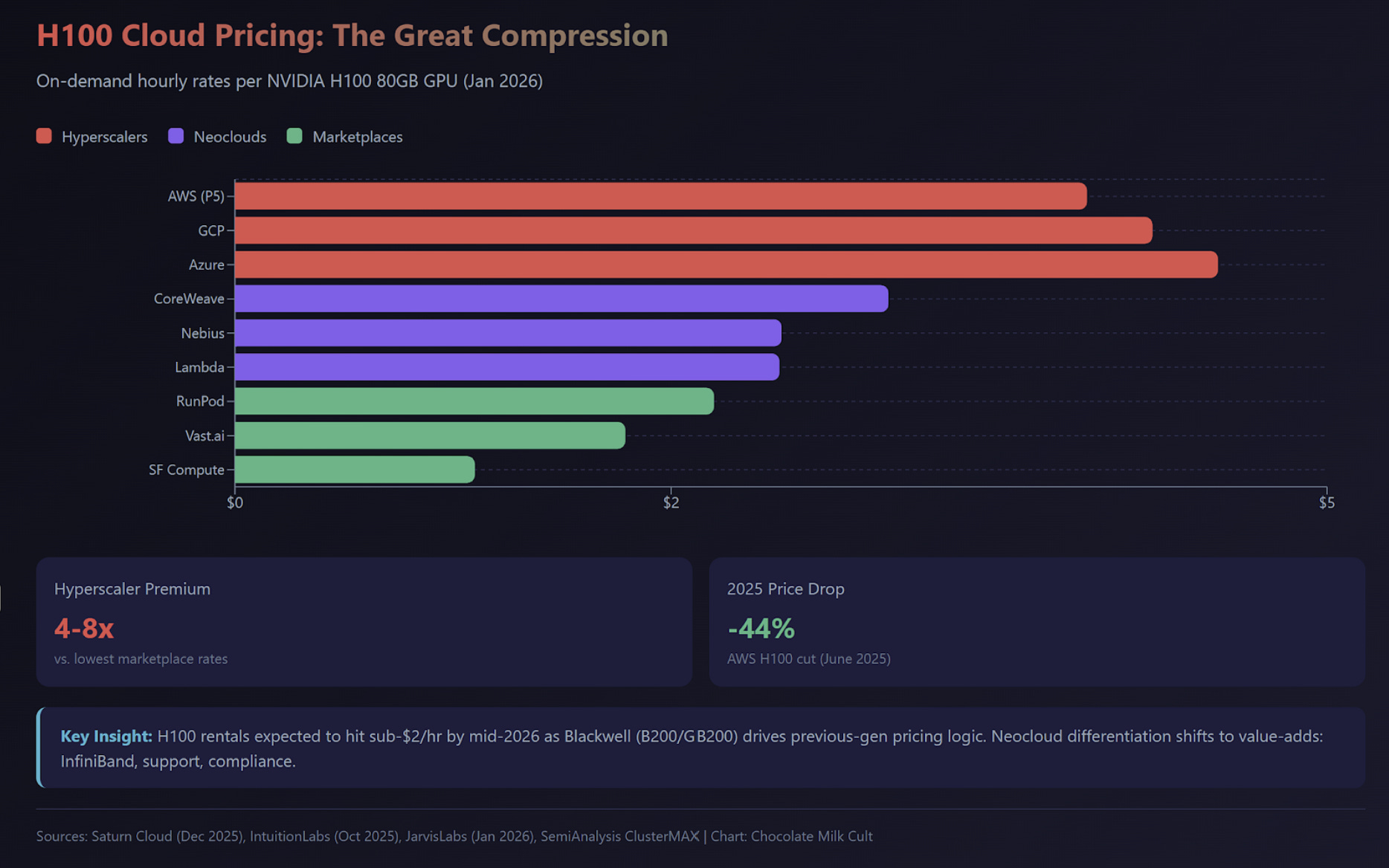

The Neoclouds (e.g., CoreWeave, Applied Digital): Their entire business model is selling GPU cycles with better performance and economics than the hyperscalers. For them, maximizing GPU utilization isn’t an optimization; it is their core product and competitive differentiator. They adopt this because it is existential to their business.

The Model Builders (e.g., Stability AI, Midjourney): Their primary currency is research velocity. The faster they can train a model or run an experiment, the faster they can innovate. They adopt this because eliminating I/O bottlenecks directly compresses their time-to-market, which is their primary competitive advantage.

The “Impossible Problem” Enterprise (e.g., The Sphere, Genomics England): These are organizations whose core mission generates data at a scale and velocity that simply breaks traditional systems. They don’t choose an architecture like this because it’s novel; they choose it because it is the only thing that works. They are the leading-edge indicators of the problems that the rest of the market will face in two to three years.

Enterprises with AI ambitions: Banks, pharma, media companies building internal AI capabilities. They don’t have the engineering depth to optimize every layer of the stack. They want infrastructure that works without constant tuning. WEKA’s “zero-tuning” pitch matters here — less ops burden, fewer late-night pages, more time for actual AI work.

7.4 What WEKA Is Not

Worth being clear about the boundaries:

WEKA is not a model serving framework. It doesn’t replace vLLM or TensorRT-LLM. It sits underneath them.

WEKA is not a training orchestrator. It doesn’t replace Ray or your distributed training framework. It feeds them.

WEKA is not cheap. The performance comes from software architecture, but also from assuming fast hardware (NVMe, high-speed networking, dedicated cores). This isn’t a solution for teams trying to run AI on commodity gear.

WEKA is not magic for every workload. If your workload is one-shot queries with no returning users, AMG’s value diminishes. If your context windows are short, the recompute tax is small anyway. The ROI is strongest for exactly the workloads the market is moving toward — but not all workloads are there yet.

It also requires plumbing. WEKA connects via the NIXL WEKA AMG Connector and a dedicated NVIDIA Dynamo plugin. These act as the traffic cops, intercepting cache misses in frameworks like vLLM or TensorRT-LLM and routing them to the G3.5 tier. You don’t rewrite your model, but you do need to configure your KV Cache Manager to be ‘WEKA-awar

7.5 The Competitive Landscape

WEKA competes in overlapping spaces:

HPC parallel filesystems (Lustre, GPFS, DDN): The incumbents for large-scale scientific computing. Strong on raw bandwidth. Weaker on metadata, latency consistency, and the kind of random-access patterns AI generates. WEKA’s distributed metadata is a direct attack on their architectural weakness.

Enterprise NAS (NetApp, Dell, Pure): Strong on enterprise features, integration, support. Often slower and more expensive at the performance tier WEKA targets. Different buyer, different sale.

Cloud-native storage (various): Newer entrants optimized for Kubernetes, object storage, cloud-first deployment. Often lack the low-latency characteristics AI workloads need.

WEKA’s bet is that AI workloads are specific enough — and valuable enough — that purpose-built infrastructure wins over general-purpose solutions. The SPECstorage and IO500 results suggest they’re not wrong about the technical differentiation. Whether that translates to market dominance is a different question. And that is the question we will answer next.

8. Value Capture: A Financial Autopsy of GPU Efficiency

We don’t know WEKA’s internal P&L, and frankly, we don’t need to. In infrastructure software, pricing power is a function of the Value Ceiling — the maximum economic surplus a vendor creates for a customer before the customer is better off building it themselves.

WEKA’s pricing power comes from a simple arbitrage: they trade Storage Dollars (cheap, abundant) for Compute Dollars (expensive, scarce). By substituting NVMe capacity for HBM capacity, they allow customers to avoid the most punishing CAPEX cycle in history.

Before we get into scenarios, a framework for thinking about this:

Value created ≠ Value captured. WEKA can create $10M in efficiency gains for a customer and capture $1M in fees. The other $9M accrues to the customer. This is normal and healthy — it’s why customers buy. The question is: what’s the ceiling on value creation, and what fraction can WEKA plausibly capture?

Value drivers for infrastructure:

Avoided cost: Spend you don’t have to make (fewer GPUs, less recompute, lower ops burden)

Unlocked capacity: Revenue you can now generate (more users per GPU, workloads that were previously infeasible)

Risk reduction: Costs you don’t incur (downtime, data loss, SLA breaches)

Speed: Time-to-market, iteration velocity, competitive advantage

The first two are quantifiable. The second two are real but harder to model. We’ll focus on what we can calculate, acknowledging the full picture is larger.

Let’s dissect value capture across four distinct market environments.

8.1 Scenario A: The Neocloud GPU Provider

Note: To beat what is becoming a dead horse, but can be overlooked easily, this model assumes a workload shift toward stateful, multi-turn interactions (coding agents, research bots). For legacy stateless chatbots, the efficiency gain is negligible.

This is the purest case study in capital efficiency. A specialized cloud provider’s entire business is a direct function of revenue generated per unit of capital deployed. CoreWeave, Lambda, Crusoe — they’re all playing this game.

The constraint: Yield management. They sell a commodity (H100 hours). Their only levers for profit are utilization (how many hours per day each GPU runs) and density (how many customers they can pack onto the same infrastructure without performance degradation).

Baseline Model: A 100-GPU H100 Cluster (Without WEKA)

Let’s build a financial model from scratch.

Capital Expenditure (CapEx):

100x NVIDIA H100 GPUs (roughly 12–13 servers at 8 GPUs each): ~$5,000,000

High-performance networking (InfiniBand/RoCE fabric): ~$500,000

Basic storage and supporting infrastructure: ~$500,000

Total Initial CapEx: $6,000,000

Revenue assumption: Each GPU supports 10 concurrent stateful inference sessions at 75% baseline utilization, billed at $0.50 per session-hour.

100 GPUs × 10 sessions/GPU × 8,760 hours/year × 0.75 utilization × $0.50/session-hr = $3,285,000 Annual Revenue

Operating Expenses (OpEx): Assume 20% of CapEx annually for power, cooling, data center overhead, and maintenance.

$6,000,000 × 0.20 = $1,200,000 Annual OpEx

Gross Profit: $3,285,000 — $1,200,000 = $2,085,000

Gross Margin: 63.5%

Now here’s the metric that matters — Return on Invested Capital (ROIC). This tells you how efficiently the business converts capital into profit. It’s calculated as:

ROIC = Gross Profit / Invested Capital = $2,085,000 / $6,000,000 = 34.7%

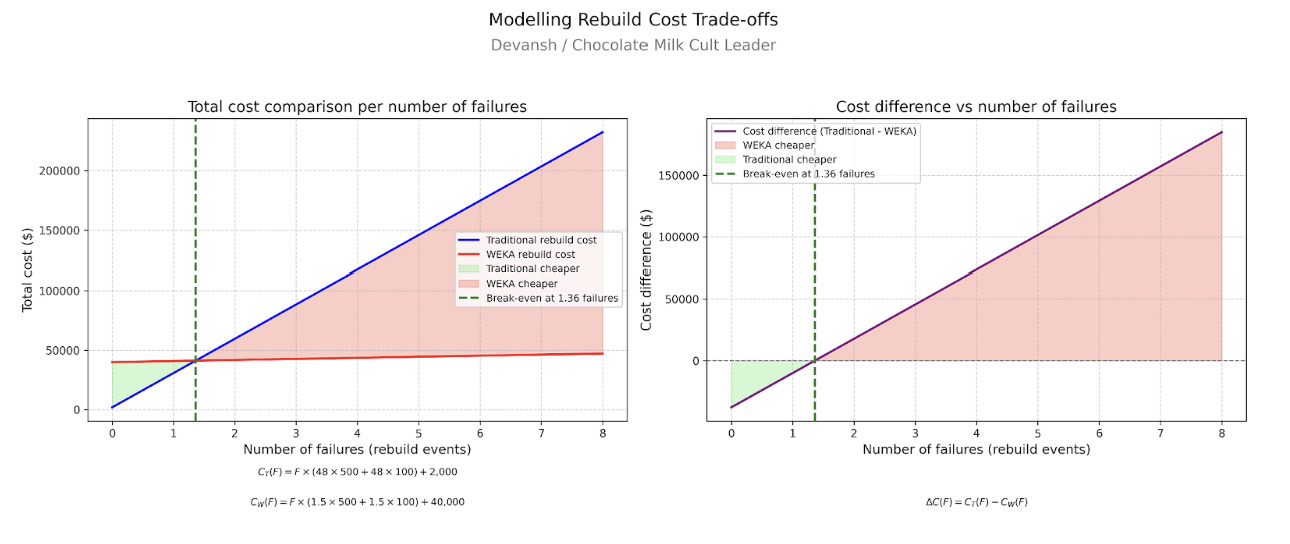

A 34.7% ROIC is solid. But it’s a capital-intensive business. You need $6M upfront to generate $2M annually. Let’s see what WEKA changes. We’ll use the 4.2x tokens-per-GPU metric from CoreWeave’s production data as our primary input since this is an IRL number.

Here’s where it gets interesting. An operator with this efficiency gain has two strategic paths:

Path A: Aggressive Growth (Constant CapEx, Expanded Revenue)

Keep the same 100-GPU fleet. Use WEKA to maximize output from existing hardware.

Incremental Investment: Assume a 3-year Total Cost of Ownership for a performance-tier WEKA deployment at this scale is $1,500,000 (roughly $500k/year).

New Asset Base: $6,000,000 (GPUs) + $1,500,000 (WEKA) = $7,500,000 Total Invested Capital

New Revenue: The 4.2x multiplier applies to session capacity per GPU.

$3,285,000 (Baseline) × 4.2 = $13,797,000 New Annual Revenue

New Financials:

Gross Profit: $13,797,000 — $1,200,000 (OpEx) — $500,000 (WEKA annual) = $12,097,000

Gross Margin: 87.7%

New ROIC: $12,097,000 / $7,500,000 = 161.3%

Read that again. ROIC went from 35% to 161%. On the same GPU hardware.

(Assumes Enterprise-grade NVMe with high write endurance)

Path B: Capital Efficiency (Constant Revenue, Reduced CapEx)

Different goal: deliver the same ~$3.3M baseline revenue with the smallest possible hardware footprint.

Required GPUs: 100 GPUs / 4.2 = 24 GPUs

New CapEx:

24x H100 GPUs and servers: ~$1,200,000

Networking and support (scaled down): ~$200,000

WEKA deployment (scaled down): ~$1,000,000

Total Initial CapEx: $2,400,000

New Financials:

Revenue: $3,285,000 (unchanged — same service level)

OpEx (reduced proportionally): ~$288,000

WEKA annual cost: ~$333,000

Gross Profit: $3,285,000 — $288,000 — $333,000 = $2,664,000

New ROIC: $2,664,000 / $2,400,000 = 111.0%

Same revenue. 60% less capital deployed. ROIC triples.

The Strategic Implication:

This isn’t just “WEKA saves money.” It’s that WEKA enables fundamentally different business strategies.

Path A is for operators who want to grow aggressively — same hardware, 4x the revenue, margins expand from 63% to 88%.

Path B is for operators who want capital efficiency — same revenue, 76% less hardware, free up $3.6M for other uses.

Both paths create a competitive moat. An operator with this efficiency can afford to lower prices to capture market share, initiating a price war that less efficient, high-CapEx competitors cannot survive. The technology becomes a tool for market consolidation.

Seen another way, for neoclouds, WEKA is not IT infrastructure; it is COGS reduction. It’s a direct lever on gross margin. This makes WEKA “sticky” — ripping it out would immediately compress margins and require either price increases (lose customers) or hardware expansion (burn capital).

8.2 Scenario B: The Vertical SaaS Provider (Legal/Medical)

The profile: High-ARPU, low-latency requirements. They process massive, unstructured documents — contracts, patient histories, regulatory filings. Users pay $50–500k/year for AI-powered analysis.

The constraint: SLA violation risk. To meet a “5-second response” guarantee for a 500-page contract analysis, they force-pin users to specific GPUs to keep the KV cache hot.

The failure mode: Massive fragmentation. They might have 50 GPUs running at 20% utilization because they can’t risk a “cold start” (recompute) on a VIP client. Each enterprise customer effectively reserves dedicated GPU capacity, even when idle.

Baseline Economics:

50 H100 GPUs required to guarantee availability for 200 enterprise clients

Average utilization: 20% (fragmentation from session pinning)

GPU CapEx: 50 × $50,000 = $2,500,000

Many clients experience SLA breaches during peak load (30%+ of interactions exceed latency target)

Churn risk: clients paying $100k/year don’t tolerate broken experiences

With WEKA (Stateless Architecture):

AMG enables treating the GPU cluster as a liquid pool. Any GPU can serve any request by fetching state from NVMe in sub-second latency.

New economics:

20 H100 GPUs handle the same peak load (running at 90% utilization instead of 20%)

Hard savings: 30 GPUs × $50,000 = $1,500,000 CapEx avoided

SLA compliance: 95%+ of requests meet latency targets (up from ~70%)

Engineering savings: No team dedicated to writing complex “sticky routing” logic

But the real value isn’t the GPU savings. It’s the revenue protection. If 30% of interactions were previously broken (latency spikes, timeouts, recompute delays), that’s 30% of touchpoints eroding customer trust.

Model the impact:

200 enterprise clients at $100k ACV = $20M ARR

Assume 15% of clients are “at risk” due to poor experience

At-risk revenue: $3M

Assume fixing SLA compliance retains 50% of at-risk clients

Protected revenue: $1.5M/year

Combined with $1.5M in avoided GPU CapEx, the total value ceiling is $3M in year one, with the revenue protection compounding annually.

WEKA isn’t selling storage here. They’re selling a 60% reduction in hardware overhead plus an insurance policy against enterprise churn. They can price at a premium to commodity storage because the alternative is buying $1.5M of NVIDIA silicon and still losing clients to bad latency.

8.3 Scenario C: The Agentic Platform

The profile: Platforms hosting autonomous agents — coding assistants, research synthesizers, workflow automators. These agents run for minutes to hours, accumulate gigabytes of context, pause, resume, and coordinate with sub-agents.

The constraint: Unit economic inversion. An agent that runs for 30 minutes accumulates substantial context. If it sleeps and wakes up later, without a persistent state, the system must re-read the entire history. The “Recompute Tax” scales with session length. Eventually, the cost to wake up an agent exceeds the subscription revenue it generates.

The longer your agents run, the more money you lose. Your best feature (persistent, capable agents) is your worst unit economics.

The Math That Breaks:

Agent session: 45 minutes of accumulated context

Context size: 200k+ tokens

Recompute cost on wake-up: ~60 seconds of GPU time = ~$0.04 at H100 rates

Average wake-ups per user per day: 10

Daily recompute cost per user: $0.40

Monthly recompute cost per user: $12

If you’re charging $20/month for an AI assistant, you’re spending 60% of revenue just on recompute for returning users. That’s before any other costs.

With WEKA (Marginal Cost Flattening):

Offloading state to NVMe means the cost to “wake up” an agent is the cost of data transfer (~$0.001), not the cost of re-inference (~$0.04).

Daily recompute cost per user: $0.01 (down from $0.40)

Monthly cost per user: $0.30 (down from $12)

Margin recovery: ~$11.70/user/month

For a platform with 100,000 users, that’s $1.17M/year in recovered margin. This isn’t optimization. It’s existential.

Without a persistent state, long-running agents are structurally unprofitable. The product category doesn’t work. You can build demos, but you can’t build a business.

With AMG, the cost curve flattens. Agent longevity becomes an asset, not a liability. The business model becomes solvent.

This is similar to how Akamai enabled video streaming. Before CDNs, streaming video was technically possible but economically insane — bandwidth costs would bankrupt you. Akamai didn’t invent streaming; they made the unit economics work. WEKA plays the same role for agentic AI. The tech is a prerequisite for the business model.

8.4 Scenario D: The Foundation Model Lab

The profile: R&D-centric organizations where the “product” is intellectual property and market leadership. They’re burning $10–50M/month in compute to train frontier models.

The constraint: Opportunity cost. A 2,000-GPU cluster costs ~$8,000/hour just to power on. If the filesystem chokes during a checkpoint save (which happens every few hours), the cluster idles. GPUs burning electricity, producing nothing.

Baseline Waste:

If a cluster spends 5% of its time waiting for I/O — checkpoint writes, data loading, metadata operations — that’s pure waste.

2,000 GPUs × $2.50/hour × 8,760 hours/year × 5% idle = $2,190,000/year wasted

With WEKA:

Distributed metadata handles the spikes. Checkpoints write at line rate. Stability AI reported 35% reduction in total training time.

Direct savings from eliminating I/O stalls: ~$2M/year

But that’s the wrong frame.

The Real Value: Research Velocity

The value of R&D is notoriously hard to model, but we can borrow from portfolio theory. Each research project is a “call option” — small probability of massive payoff (a breakthrough model), high probability of incremental learning.

The total value of your R&D portfolio is a function of how many options you can buy. More experiments = more shots on goal = higher probability of hitting a breakthrough.

Here’s the reframe:

Baseline: Fixed $20M annual R&D compute budget allows 10 major training experiments per year

Performance delta: 35% reduction in training time (Stability AI’s reported number)

Impact: Same $20M budget now runs 10 / 0.65 ≈ 15 major experiments per year

This is not a 35% cost saving. It’s a 50% increase in shots on goal for the same capital burn.

For organizations in a winner-take-all market, increasing the probability of landing the next breakthrough model is effectively infinite value. Two weeks faster to SOTA (state of the art) could be the difference between releasing before OpenAI or after.

Labs will pay almost any price for a storage layer that guarantees GPUs never stop. The value here isn’t the cost of hardware — it’s the increase in expected value of the entire R&D portfolio. It’s an investment in the probability of survival and market dominance.

8.5 The Value Capture Map

Pulling it together, the pattern is clear: WEKA’s value scales with GPU spend and workload statefulness.

A team with 10 GPUs running stateless queries might see $10–50k/year in value. Worth it, maybe, but not transformative.

A neocloud with 1,000 GPUs running stateful inference sees $5–10M/year in value. That’s strategic infrastructure.

A frontier lab burning $50M/month sees WEKA as insurance against the most expensive idle time in computing history.

8.6 The Investment Thesis

Storage vendors trade at 4–6x revenue because storage is deflationary. Bits get cheaper. Margins compress. WEKA should be priced as a Compute Derivatives Platform.

The distinction matters:

Revenue growth is indexed to GPU deployment, not data storage growth

Churn is defended by physics — you can’t rip them out without accepting worse latency or rewriting your stack

Pricing power scales with GPU scarcity — as GPUs get more expensive, the value of making them efficient goes up

They capture a “tax” on the compute layer without owning the compute layer

This is the NetApp playbook from enterprise NAS, applied to AI infrastructure. Category creators capture disproportionate value because customers associate the solution with the brand. “We need a WEKA” becomes the shorthand for “we need a GPU memory tier.”

The Risk: Competition compresses capture rates. If DDN, NetApp, or a well-funded startup builds comparable technology, WEKA’s ability to capture 20–30% of the value created drops. They’d compete on price, capture rates fall to 10–15%, and it becomes a commodity infrastructure play.

The moat is architectural lead time and switching costs, not permanent technical differentiation. The window to establish category ownership is measured in years (months now that AI coding agents have dramatically reduced the cost of software), not decades.

In a world where “Compute is the new Oil,” WEKA is positioning as the high-efficiency pipeline that ensures no drop is spilled. Whether they capture that position depends on sales execution, competitive response, and whether the market moves toward the stateful workloads where their advantage is largest.

9. Conclusion: The Bet

WEKA is wagering on a specific future: one where AI systems remember.

If AI stays stateless — single-turn, disposable context, no persistent reasoning — then WEKA is a very good storage company selling to a niche. Profitable, but bounded.

If AI becomes stateful — agentic, multi-turn, accumulating — then WEKA is positioned at exactly the seam where the old infrastructure breaks.

The interesting thing is: WEKA doesn’t need to win for the thesis to be right. Recompute is waste. Pinning is waste. Session loss is waste. Someone will solve these problems, because the economics demand it. If WEKA executes poorly, a competitor captures the value. If the category gets commoditized, customers capture the value. But the value gets created regardless.

This is a good floor for any organization to start from.

To end, I’ll leave you with a thought that might help you decide Weka deserves more of your attention. The question isn’t whether your system needs to be fast. Every system needs to be fast. The question is whether your system can afford to forget. Your answer to that determines how much attention this crew deserves.

Thank you for being here, and I hope you have a wonderful day,

Dev <3

If you liked this article and wish to share it, please refer to the following guidelines.

That is it for this piece. I appreciate your time. As always, if you’re interested in working with me or checking out my other work, my links will be at the end of this email/post. And if you found value in this write-up, I would appreciate you sharing it with more people. It is word-of-mouth referrals like yours that help me grow. The best way to share testimonials is to share articles and tag me in your post so I can see/share it.

Reach out to me

Use the links below to check out my other content, learn more about tutoring, reach out to me about projects, or just to say hi.

Small Snippets about Tech, AI and Machine Learning over here

AI Newsletter- https://artificialintelligencemadesimple.substack.com/

My grandma’s favorite Tech Newsletter- https://codinginterviewsmadesimple.substack.com/

My (imaginary) sister’s favorite MLOps Podcast-

Check out my other articles on Medium. :

https://machine-learning-made-simple.medium.com/

My YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/@ChocolateMilkCultLeader/

Reach out to me on LinkedIn. Let’s connect: https://www.linkedin.com/in/devansh-devansh-516004168/

My Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/iseethings404/

My Twitter: https://twitter.com/Machine01776819

Really enjoyed this piece, haha especially the way you framed state as the real bottleneck and “recompute tax” as an economic problem, not just a latency annoyance.

I’m working a layer above where WEKA lives, on what we’ve been calling an Awakened OS: an agent OS that gives small/medium models persistent semantic memory (structured records, scoring, Vault vs Workbench, etc.) instead of letting them forget every conversation. The pattern we’re seeing maps to your thesis almost exactly: the biggest wins come from keeping state and reusing it, not from just throwing more flops or bigger models at the problem.

Reading this made me think that future agent OSes are going to need exactly this kind of fast, shared KV plane underneath – GPUs acting as mostly stateless compute pulling from a “memory cathedral” that lives on something like NeuralMesh. It’s encouraging to see infra folks and agent-OS folks converging on the same heading: compute is plentiful, state is precious.

Incredibly dense write up, and I appreciated your analysis.

"NVIDIA and WEKA have formalized the memory tiers for AI factories... Based on this classification, Weka would be in 1.5."

That's something the market hasn't yet ratified. Some would say 2.5 or even 3.5 depending on network topology and distance/latency. Nvidia's own storage initiatives will require revising the formal classifications to include NVMe-based shared storage with support for GPU-initiated storage access. Once that happens, I would expect uncertainty to evaporate.

Similarly, Nvidia putting their thumb on the scales of AI storage will change the trajectory for everyone. I expect them to create a framework with less differentiated value for any single storage provider. Nvidia likes to position themselves as a neutral third party, but I suspect they'll come across more like a governing body on this topic.