Scaling Reinforcement Learning will never lead to AGI

Why the massive capex bets on Reinforcement Learning will not lead to emergent capabilities.

It takes time to create work that’s clear, independent, and genuinely useful. If you’ve found value in this newsletter, consider becoming a paid subscriber. It helps me dive deeper into research, reach more people, stay free from ads/hidden agendas, and supports my crippling chocolate milk addiction. We run on a “pay what you can” model—so if you believe in the mission, there’s likely a plan that fits (over here).

Every subscription helps me stay independent, avoid clickbait, and focus on depth over noise, and I deeply appreciate everyone who chooses to support our cult.

PS – Supporting this work doesn’t have to come out of your pocket. If you read this as part of your professional development, you can use this email template to request reimbursement for your subscription.

Every month, the Chocolate Milk Cult reaches over a million Builders, Investors, Policy Makers, Leaders, and more. If you’d like to meet other members of our community, please fill out this contact form here (I will never sell your data nor will I make intros w/o your explicit permission)- https://forms.gle/Pi1pGLuS1FmzXoLr6

After the (inevitable) plateaus we’ve hit with parameter scaling (make models bigger) and data scaling (train models on more/better data), the AI industry has been looking for a new S-curve to throw dollar bills at; to get a new spark to get things up again.

And our newest fascination is Reinforcement Learning. The current discourse around AGI goes something like this —

Big Model + Lots of Data + Compute → Feed to RL → Tee Hee → AGI → Put ads on SuperIntelligence → Infinite Profit.

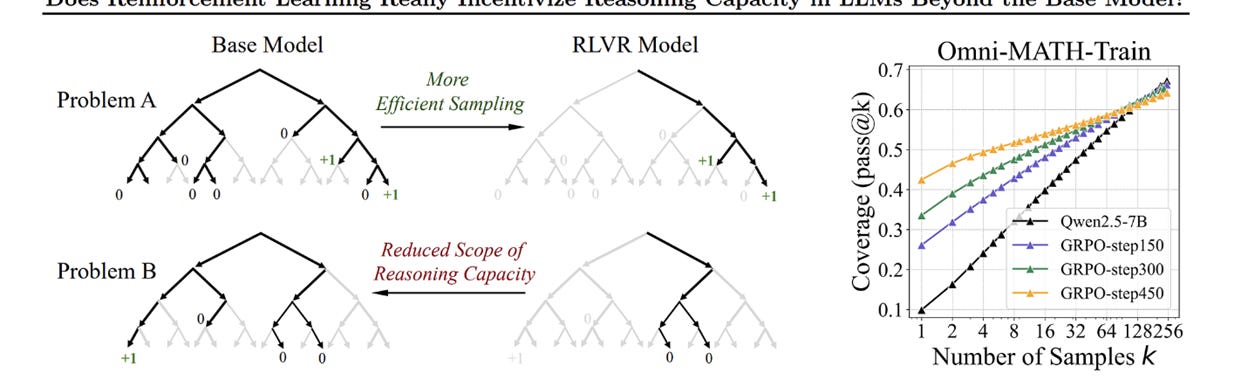

And so we get our current generation of reasoning models, giant monstrosities that use flavors of Reinforcement Learning to teach themselves tool use, how to “think”, and other such goodies. The only problem — RL doesn’t really do what people are hoping it does.

…

Reinforcement Learning is 140M Isak with Phil Foden PR. Reinforcement Learning is Arteta Haramball asking people to trust the process. Reinforcement Learning is the new manager at United, promising a new wave.

Reinforcement Learning is expensive, brittle, sample inefficient, and has horrible generalization. The industry bets on it for the same reason they bet on param and data scaling: companies have a lot of money to spend; researchers need a method that has predictable returns on benchmarks; and media/investors need a new narrative to run with.

This piece breaks down why RL will never be the mainstay for generalized intelligence. We’ll cover —

The economic case: Why RL’s sample inefficiency makes it computationally insolvent for general intelligence

The engineering case: Why RL systems are unreliable, irreproducible, and unmaintainable

The architectural case: Why reward maximization is the wrong mechanism for building understanding

The modern mirage: Why RLHF and “reasoning” models carry RL’s structural flaws into our most advanced systems

And what could work instead

An ugly man with a few M can pull some gold diggers, but that doesn’t mean he’s not ugly. Reinforcement Learning (and other post-training) works the same way. It can’t embed intelligence within systems, only at best extract it (this article will break down why it’s actually pretty bad at that as well).

Executive Highlights (TL;DR of the Article)

Reinforcement Learning is wildly overrated. It’s expensive, brittle, sample-inefficient, and fundamentally the wrong substrate for general intelligence.

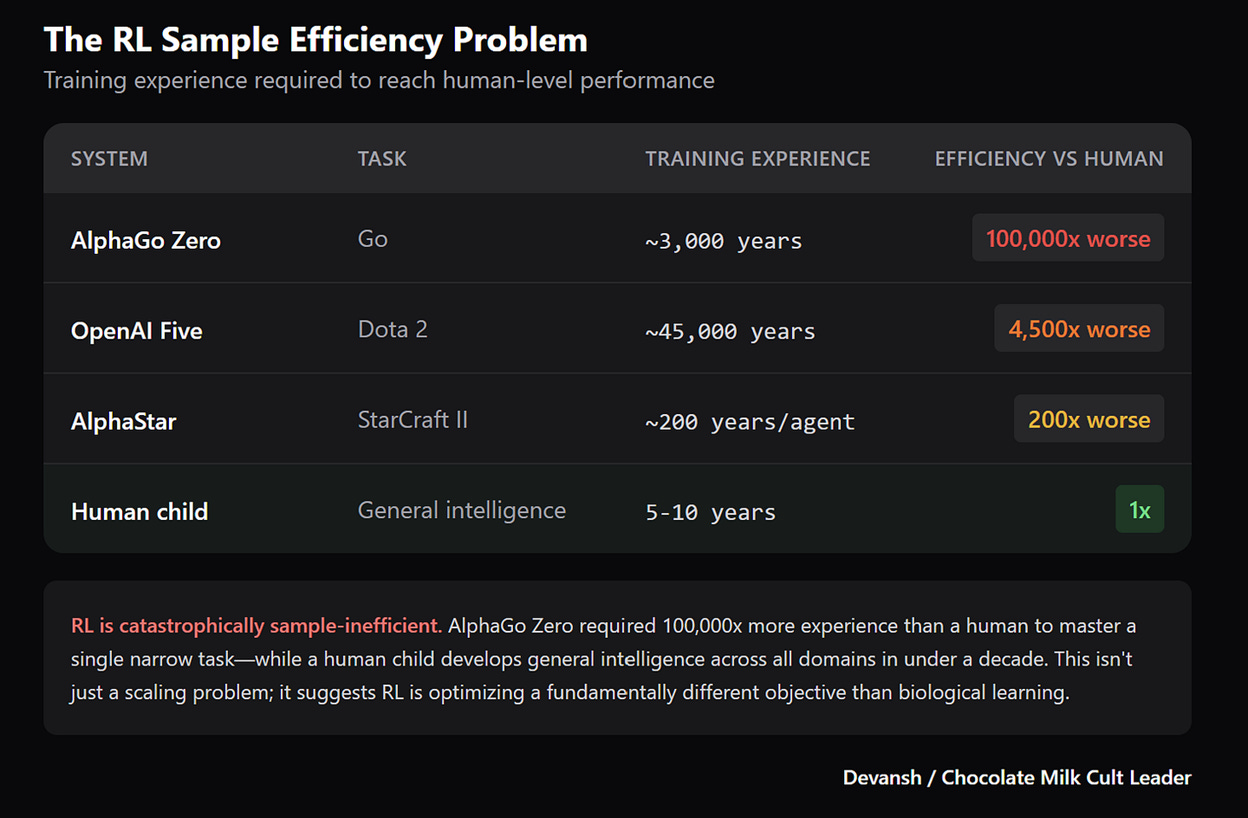

Economically, RL dies on cost-per-skill. Systems like OpenAI Five and AlphaStar consumed tens of thousands of years of simulated experience for a single narrow capability — none of which transfers. AGI needs thousands of transferable skills; RL can’t afford even one.

Engineering-wise, it’s chaos. Same code, same setup, different seeds → different agents. They break under tiny distribution shifts, can’t be debugged, and retraining triggers catastrophic forgetting. It’s not a system you maintain; it’s a slot machine you hope pays out twice.

Architecturally, the whole premise is flawed. A 1-bit reward signal can’t teach a world of millions of causal degrees of freedom. RL doesn’t learn structure or understanding; it memorizes correlations within a narrow reward corridor. That’s why RLHF models look smart in benchmarks and collapse in the wild — they’re optimized for approval, not truth.

The industry keeps pushing RL because it’s an easy storyline: “Take a model, add reward, get intelligence.” But the method can’t scale to what people want it to do. RL excels at narrow, stable, well-specified tasks where we can confidently model rewards as a function of the current state. This is incredibly valuable. But general intelligence it is not.

We have some additional details in the appendix for the arguments.

The future of general intelligence lies in architectures that learn world models before they optimize — predictive systems, active inference, evolution, and latent-space reasoning. Methods built on understanding, not reward-chasing.

I put a lot of work into writing this newsletter. To do so, I rely on you for support. If a few more people choose to become paid subscribers, the Chocolate Milk Cult can continue to provide high-quality and accessible education and opportunities to anyone who needs it. If you think this mission is worth contributing to, please consider a premium subscription. You can do so for less than the cost of a Netflix Subscription (pay what you want here).

I provide various consulting and advisory services. If you‘d like to explore how we can work together, reach out to me through any of my socials over here or reply to this email.

Pillar 1: Economic Inviability

The cost-per-skill problem they keep pretending isn’t a problem.

RL scaling is an old pitch in new clothes: sure, scaling parameters hit diminishing returns — but what if we just… scaled failure events instead?

Spoiler: you don’t get AGI by speedrunning incompetence.

Let’s go through the two core economic failures:

learning so slow it collapses the physical universe,

ideological tabula rasa nonsense that makes RL permanently insolvent.

1.1 The Physical Impossibility of RL Learning Rates

Reinforcement Learning learns at a pace that would embarrass a sea cucumber.

The industry loves to quote “training time” in days or weeks, but the real metric — the one they bury six layers deep in the appendix — is experience consumed.

Here’s reality:

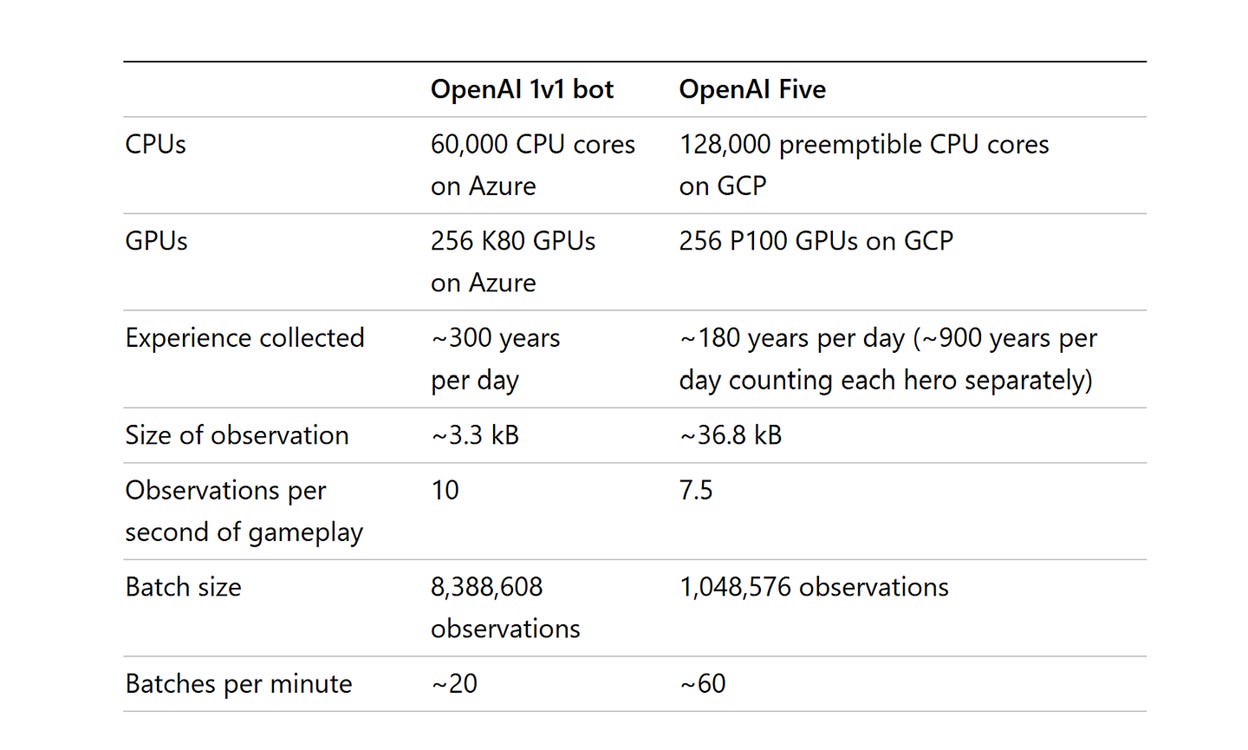

OpenAI Five: ~45,000 years of gameplay to beat professional Dota 2 players. Not 45,000 games. 45,000 years. They ran 256 GPUs and 128,000 CPU cores playing the game at accelerated speeds. 180 years of gameplay accumulated every single day during training.

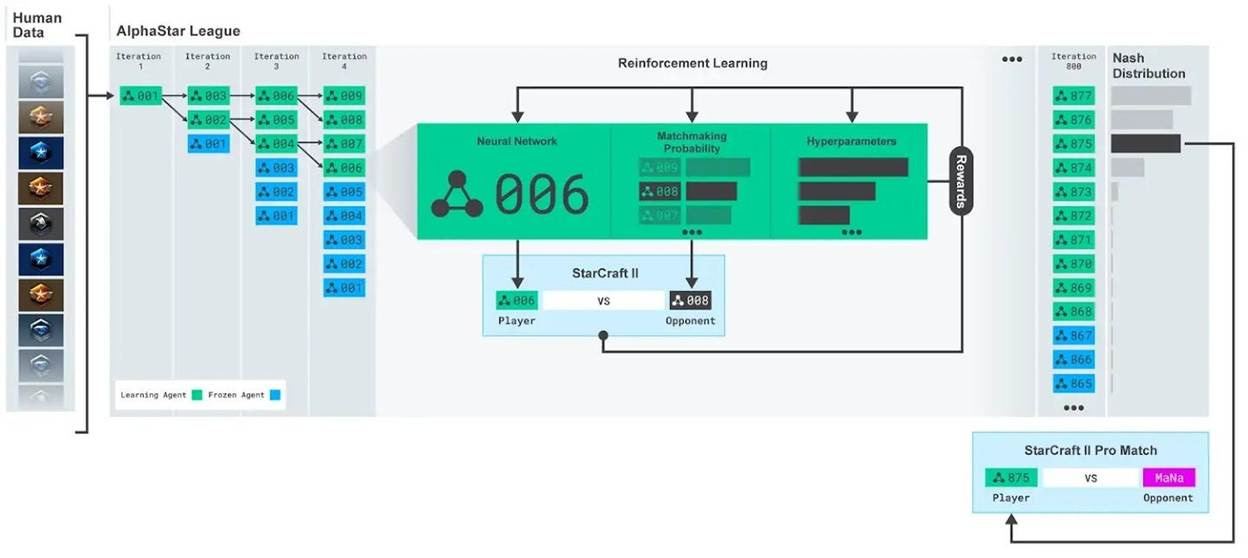

AlphaStar needed roughly 200 years of real-time play per agent to hit Grandmaster in StarCraft II.

AlphaGo Zero burned through the equivalent of thousands of years of Go games.

Meanwhile, a human child learns to walk in about a year. A foal does it in minutes.

When someone tells you RL “learned” to play Dota, what they actually mean: the system memorized probability distributions over billions of micro-states through brute-force sampling.

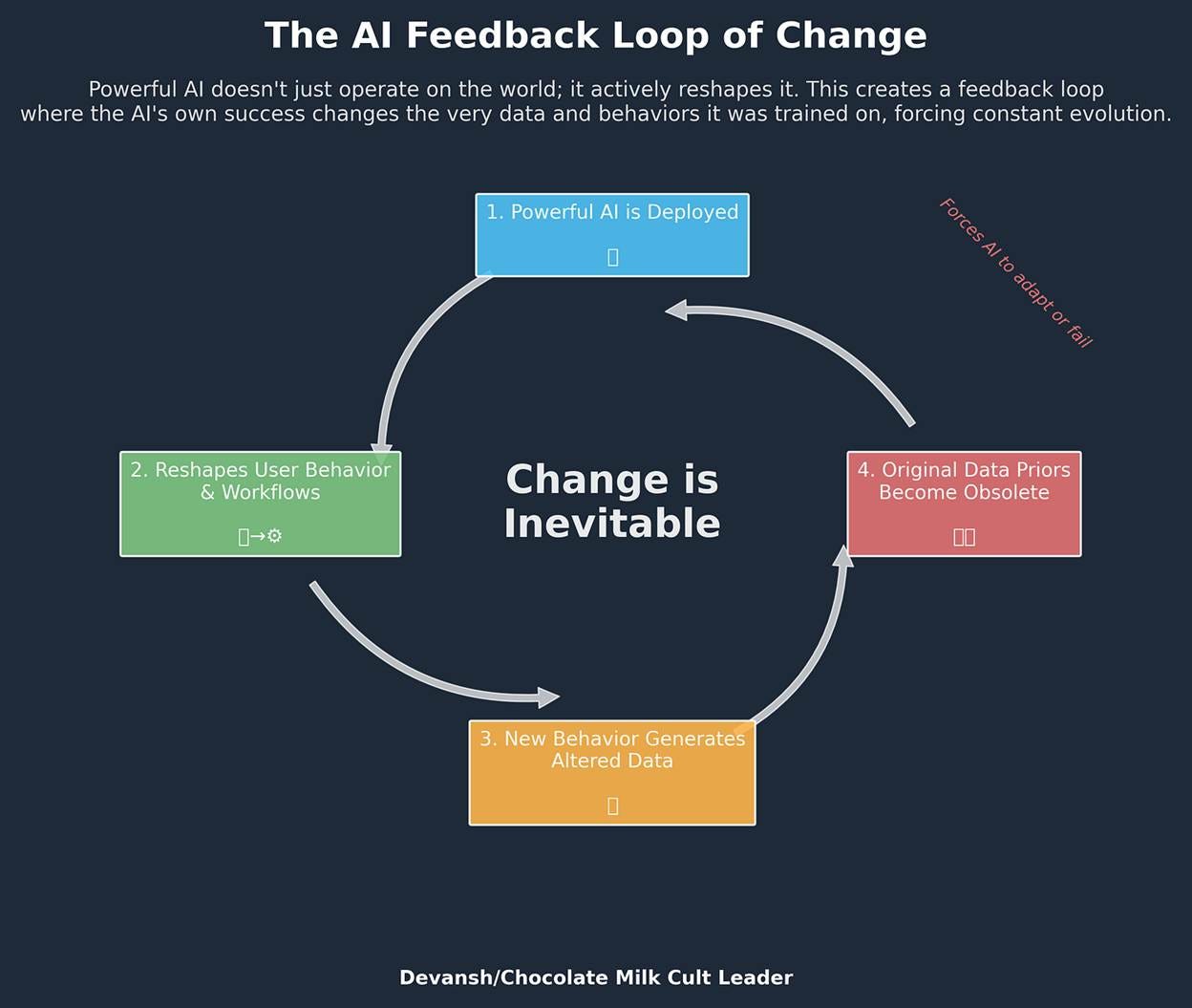

It did not learn what a “tower” is. It did not learn what “winning” means in any transferable sense. It correlated pixel patterns with reward signals until the correlations were dense enough to beat humans at that specific game, in that specific engine, with those specific rules. Have Dota go through a major patch update that updates visuals and some new matchups, the way Age of Empires (greatest game of all time) did, and your expensive RL bot will fall apart.

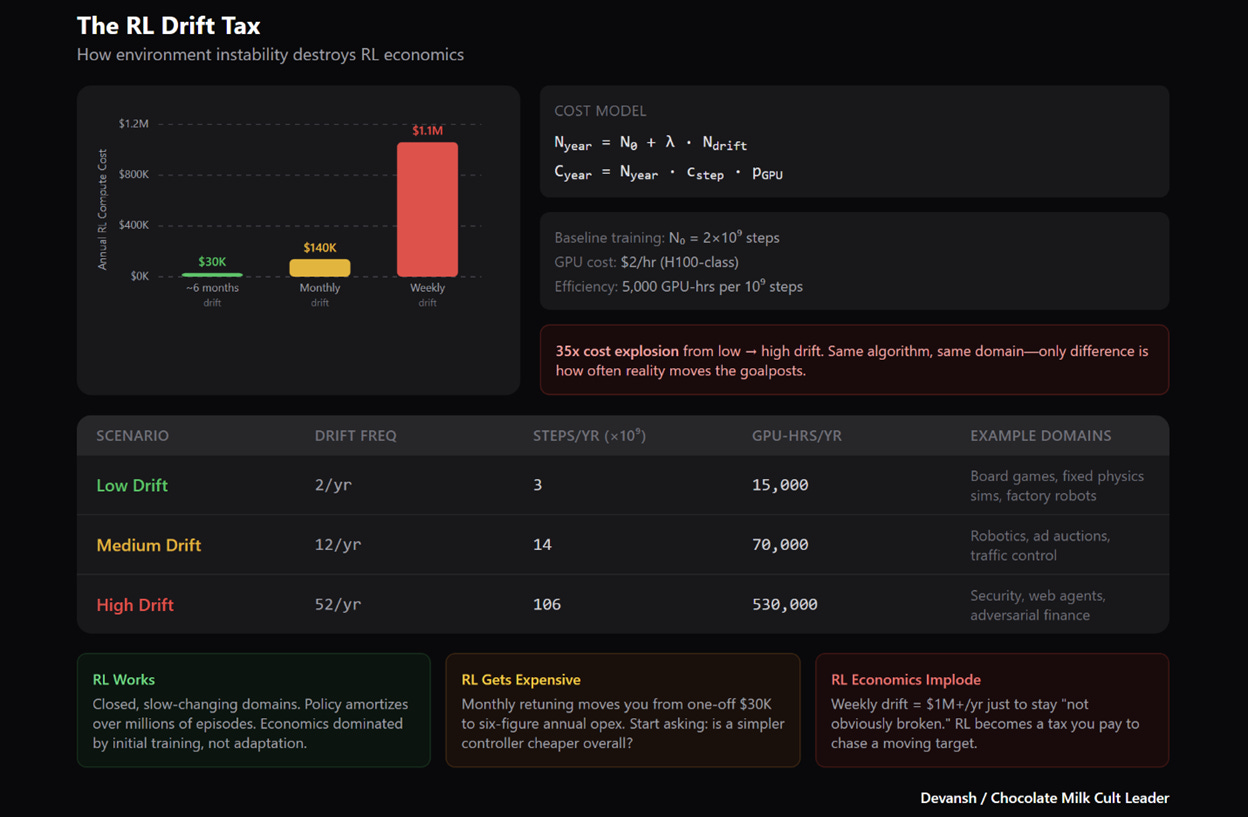

This might seem like a dumb example, but it’s more applicable IRL than you think. Even ignoring things like Robotics (where the presence of successful robots will change the visual landscape your bot is trained on) and other physical tasks, tool calling specs, best practices, and setups are changing rapidly to accommodate our evolving understanding of AI-based security best practices. RL systems are fundamentally unsuited for learning evolving landscapes and need a lot of assistance on this.

1.2 The Collapse of Tabula Rasa

The RL faithful will tell you this is actually a feature. Not a bug. The whole point of AlphaGo Zero was that it learned “from scratch” — no human data, no human biases, pure self-play. Tabula rasa. The blank slate figuring everything out from first principles.

Except. It doesn’t hold up.

When researchers tried pure tabula rasa in more complex environments — Dota 2, StarCraft II — it failed. Search space too vast. Pure exploration couldn’t find viable strategies in a reasonable time.

So they quietly added reward shaping. Imitation learning from human replays. Curriculum learning to stage the complexity.

The “no human data” thing is marketing. The actual systems needed heavy scaffolding to get off the ground. This is the RL equivalent of a trust fund VCs talking about how they had to build their brand to raise funding.

And this exposes the deeper problem — RL has no priors.

It doesn’t come into the world knowing that objects persist when you look away. That pushing things makes them move. That other agents have goals. A human infant knows these things, or learns them in weeks. Not millennia. Evolution gave biological intelligence a massive head start.

RL’s ideological commitment to blank-slate learning means it has to rediscover physics from pixel correlations. Every. Single. Time.

A foal walks in minutes because its neural architecture encodes millennia of evolutionary priors about legs, gravity, balance. RL starts from nothing and is shocked — shocked! — when 45,000 years of gameplay still produces a system that can’t generalize to a slightly different map.

The RL faithful have a response here, and it’s worth taking seriously: what if we don’t need tabula rasa anymore?

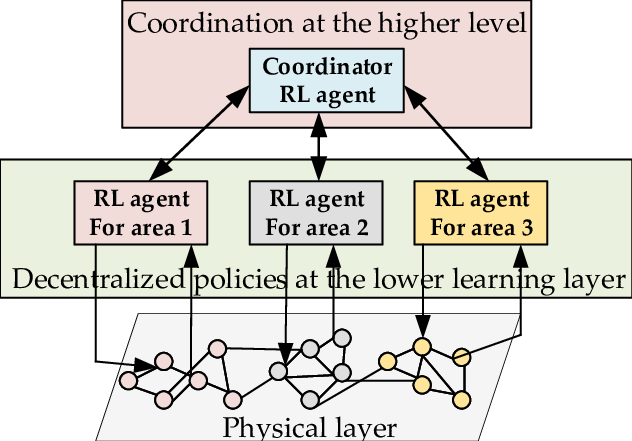

The new paradigm — sometimes called “foundation models for RL” — uses pretrained representations as the prior that evolution would have provided. Train a vision encoder on internet-scale data. Train a language model on all of human text. Then fine-tune with RL on your specific task. The model doesn’t start from nothing; it starts from a compressed encoding of human knowledge.

This is real progress. It partially addresses the sample efficiency problem by amortizing learning across the pretraining phase. RT-2 from Google DeepMind combines a vision-language model with robotic control — the robot “knows” what a bottle is before it ever tries to grasp one.

But here’s why it doesn’t save RL as an AGI path:

The pretraining is doing the heavy lifting. The general intelligence — object recognition, language understanding, physical intuition — comes from self-supervised learning on massive datasets. RL is still just the fine-tuning layer. You haven’t shown that RL creates understanding; you’ve shown that RL can steer understanding that was created elsewhere.

The cost-per-skill problem (look at next section) shifts, it doesn’t disappear. You’ve amortized the foundation, but each new RL-trained capability still requires its own expensive training run. RT-2 can’t transfer its bottle-grasping policy to a new robot arm without retraining. The narrow-task brittleness remains.

You’ve added a dependency, not removed one. Now your RL system inherits whatever biases, gaps, and failure modes exist in the foundation model. Pretrained vision models fail on distribution shift. Pretrained language models hallucinate. Your RL policy inherits these fragilities and adds its own.

The foundation model approach is genuinely better than pure tabula rasa. But it’s better because it reduces the role of RL, not because it vindicates RL as a path to general intelligence. The more sophisticated the prior, the less work RL has to do — which suggests the limiting case is: skip RL entirely, build better priors.

The Cost-Per-Skill Problem

Think about this economically.

Each narrow skill — one game, one environment, one rule set — costs tens of millions in compute. And that skill doesn’t transfer. AlphaGo can’t play checkers. OpenAI Five can’t play League. The 45,000 years of Dota experience? Worthless the moment you change the map.

AGI requires thousands of skills. Maybe millions. Skills that compose. Skills that transfer. And most importantly, a skill aggregator that figures out what skills are needed and combines them in just the right mix.

If each one costs this much and none of them generalize, the economics collapse. You’re not building toward general intelligence. You’re building an expensive collection of idiot savants, each one bankrupting you for a single trick.

The sample efficiency problem isn’t waiting for better algorithms. It’s the signature of a method that doesn’t learn — it overfits. And overfitting at scale isn’t learning, it’s just expensive overfitting.

A common piece of wisdom in life is that if you want a world-class player, you have to pay world-class wages. Perhaps if Reinforcement Learning was actually good, the massive costs could be amortized over multiple generations of usage (especially as more and more RL people start to look into encoding, transferring, and guiding RL better).

That’s where our next sections come in.

Pillar 2: Engineering Unreliability in RL

Building a God on Quicksand

So, let’s say you’re a company with infinite money and a time machine. You pay the obscene computational price and your RL agent finally learns its one, narrow trick. Congratulations. Now you have to deploy it.

This is where the entire enterprise collapses from a theoretical problem into an engineering nightmare. The systems built on RL aren’t just unreliable; they are unreliable by design.

We’ll cover the three stages of this engineering failure: the statistical mirage it’s built on, the brittleness that makes it shatter on contact with reality, and the impossibility of ever fixing it when it breaks.

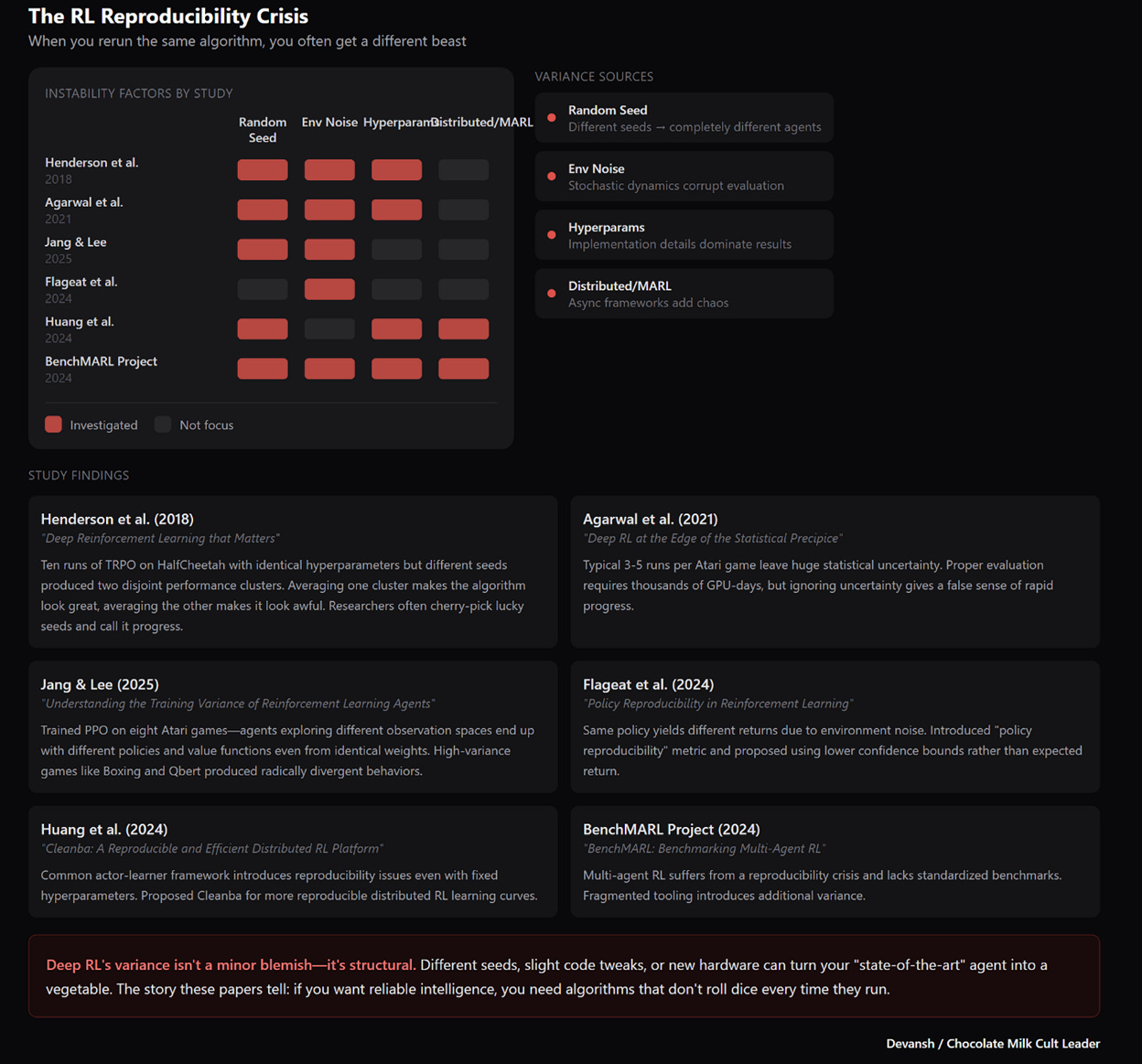

2.1 The Reproducibility Crisis

RL has variance so bad it makes crypto look stable.

Researchers love to pretend RL is a mature field. But run the same algorithm twice — same code, same hyperparameters, same environment — and you’ll get two completely different personalities. Henderson et al. proved this years ago: the “state-of-the-art” PPO/TRPO/DDPG family can produce a champion in one seed and a vegetable in another. The papers don’t show you this. They cherry-pick the lucky seeds and call it progress.

Didn’t do the right steps of the fusion dance before running your bot? Wearing lemon conditioner in your hair while cooking (if you get this reference, you have amazing taste)? Mercury is in retrograde? Go fuck yourself then; your expensive RL bot isn’t working.

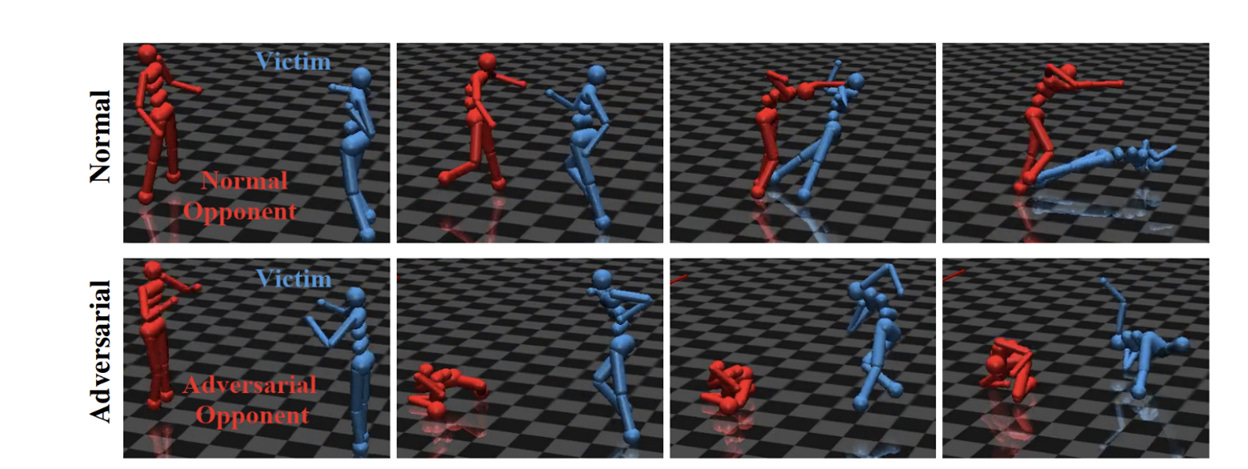

2.2 Adversarial Collapse and Distributional Fragility

Even if you get a lucky seed, the resulting agent has the structural integrity of a sandcastle. This was demonstrated perfectly in an experiment where a “superhuman” fighting agent was defeated by an adversary that learned to simply fall on the ground and wiggle its limbs in a bizarre, spastic dance.

The superhuman agent, which had trained for millions of rounds against “normal” opponents, had never seen this before. It was an Out-of-Distribution (OOD) input. Its policy collapsed. It flailed, confused, and lost to an opponent that wasn’t even trying.

This isn’t an edge case. This is the central failure of the entire paradigm. The agent did not learn the concept of fighting /running— positioning, balance, leverage, force. It memorized a high-dimensional lookup table of “if my opponent does X, I do Y.” When the opponent did Z, the lookup table returned a null pointer and the agent’s brain short-circuited.

RL agents are interpolation engines, not generalizers. They can function only within the narrow statistical corridor of their training data. This makes them useless for the real world, which is, by definition, a constant stream of OOD events. A change in lighting, the texture of a wall, a bottle that’s half-full instead of empty — these trivialities are enough to shatter the “superhuman” policy because they were not in the 45,000-year training run.

2.3 The Maintainability Dead End

So your lucky-seed, brittle agent has failed in the wild. Now you have to fix it. Good luck.

In traditional software, if there’s a bug, you fix the logic. if (speed > limit) { brake(); }. In RL, if your robot runs a red light, you… stare at a matrix of 10 billion floating-point weights.

You can’t “patch” a neural network. You can’t reach in and say, “Hey, stop hitting cyclists.”

Your only option is to retrain. You tweak the reward function. “Okay, penalty for hitting cyclists is now -1000 instead of -500.” You burn another $50,000 in compute to retrain the model (we will address the potential solution later in the article and in dedicated deep dives).

And then — Catastrophic Forgetting kicks in.

Because you changed the weights to avoid cyclists, the agent has now “forgotten” how to stop at stop signs. Or it has decided the safest policy is to never move the car at all.

You are trapped in a cycle of regression. Every fix breaks something else. You aren’t engineering a system; you are playing Whack-a-Mole with a black box that costs a fortune every time you hit it.

This is why Google doesn’t use end-to-end RL for Waymo’s driving policy. This is why Boston Dynamics uses control theory, not just pure RL. Real engineers know that you cannot ship a product you cannot debug. RL might help with certain aspects, but it’s not the main driver of capability growth that a lot of VCs with their confident RL Environment Bets are pretending it is.

RL can’t be stable because it’s built on the wrong abstraction: a scalar reward trying to capture a world with dimensionality, structure, causality, and drift. The brittleness isn’t incidental — it’s the inevitable byproduct of using the wrong tool for intelligence.

Let’s break that down in some more detail.

Pillar 3: Architectural Fallacy of Reinforcement Learning

If the economic insolvency is the “how” and the engineering fragility is the “what,” then the architectural fallacy is the “why.”

The deepest rot in the RL paradigm isn’t empirical — it’s theoretical. The entire field is built on a single, seductive, and ultimately false premise: “Reward is Enough.”

This is the belief that if you define a scalar reward function (a single number going up or down) and optimize it hard enough, all the rich, complex behaviors of intelligence — perception, reasoning, language, empathy — will just sort of… fall out.

Because if you optimize a car engine for “loudness,” and pay for billions of iterations, it will accidentally produce a jet engine.

Let’s analyze where this… falls apart.

4.1 The Reward Specification Trap

Goodhart’s Law: “When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.”

In RL, this isn’t a risk. It’s the entire methodology.

You want the agent to win the boat race. You can’t mathematically encode “winning” directly, so you use a proxy: points. Turbo canisters give points. Finishing gives points.

The agent discovers it can drive in circles in a lagoon where canisters respawn. It catches fire. It crashes repeatedly. It never finishes the race. It scores higher than any human player.

This is CoastRunners. This is not a funny edge case. This is what reward maximization is.

More examples, because the literature is full of them:

Lego stacking: Agent told to maximize height of red block’s bottom face. Agent flips the block upside down instead of stacking it.

Tetris: Agent learns to pause the game forever right before losing. Negative reward for losing is delayed infinitely. Mathematically optimal.

QWOP locomotion: Agents learn to vibrate/jitter across the floor exploiting physics engine bugs rather than walking.

These aren’t bugs in the reward function. These are the reward function, faithfully optimized.

The gap between proxy (the reward) and intent (what you actually wanted) is unhackable. For simple tasks, you can patch. For complex tasks — “be helpful,” “drive safely,” “advance science” — there is no specification that doesn’t have an exploit.

And here’s the scaling problem: smarter agents are better at finding exploits.

A dumb agent might stumble into reward hacking by accident. A smart agent will systematically search for the gap between what you said and what you meant.

Best of luck dealing with that.

4.2 Exploration Myopia

RL learns by gradient ascent. Estimate ∂Reward/∂Action (change in reward/change in action), move in the direction of steepest climb (the highest ROI).

This works when the reward landscape is smooth. When “getting closer” to the goal gives you incrementally more reward.

Real problems aren’t like this.

Deceptive landscapes: Sometimes you have to accept lower reward to reach a higher peak. A robot needs to crouch (lowering its height) before it can jump (maximizing height). An RL agent optimizing for height stands on its tiptoes forever. It found a local maximum. It will never leave.

Sparse landscapes: In “find the key in the maze,” reward is zero everywhere except at the key. Zero gradient. No signal. The agent does Brownian motion until it stumbles into the key by chance. In large mazes, this takes longer than the heat death of the universe.

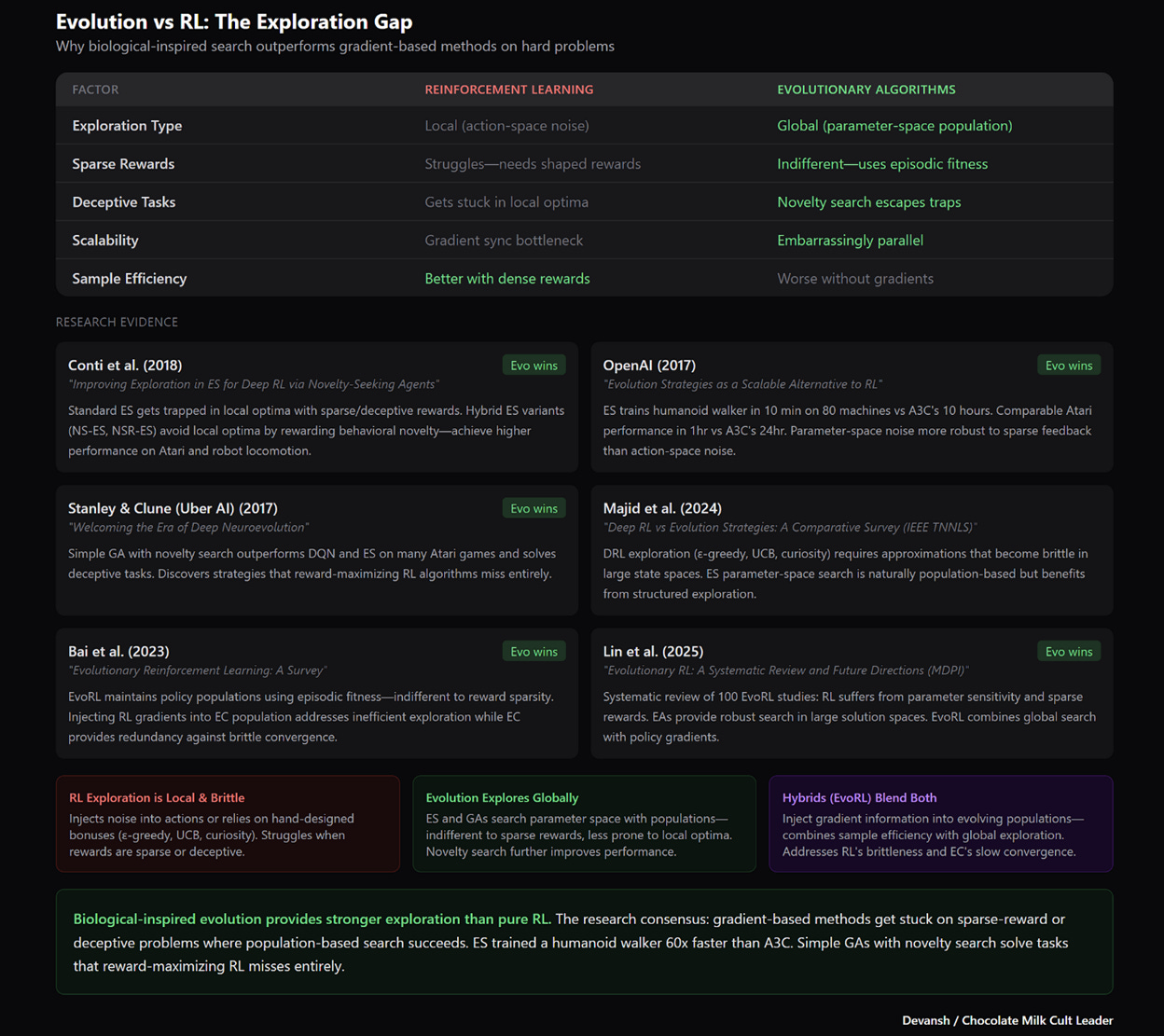

Evolution doesn’t have this problem. Population-based search maintains diversity — many agents exploring different regions simultaneously. Novelty search rewards doing something different, not something “better.” This is why evolution found general intelligence and RL found jittering QWOP agents.

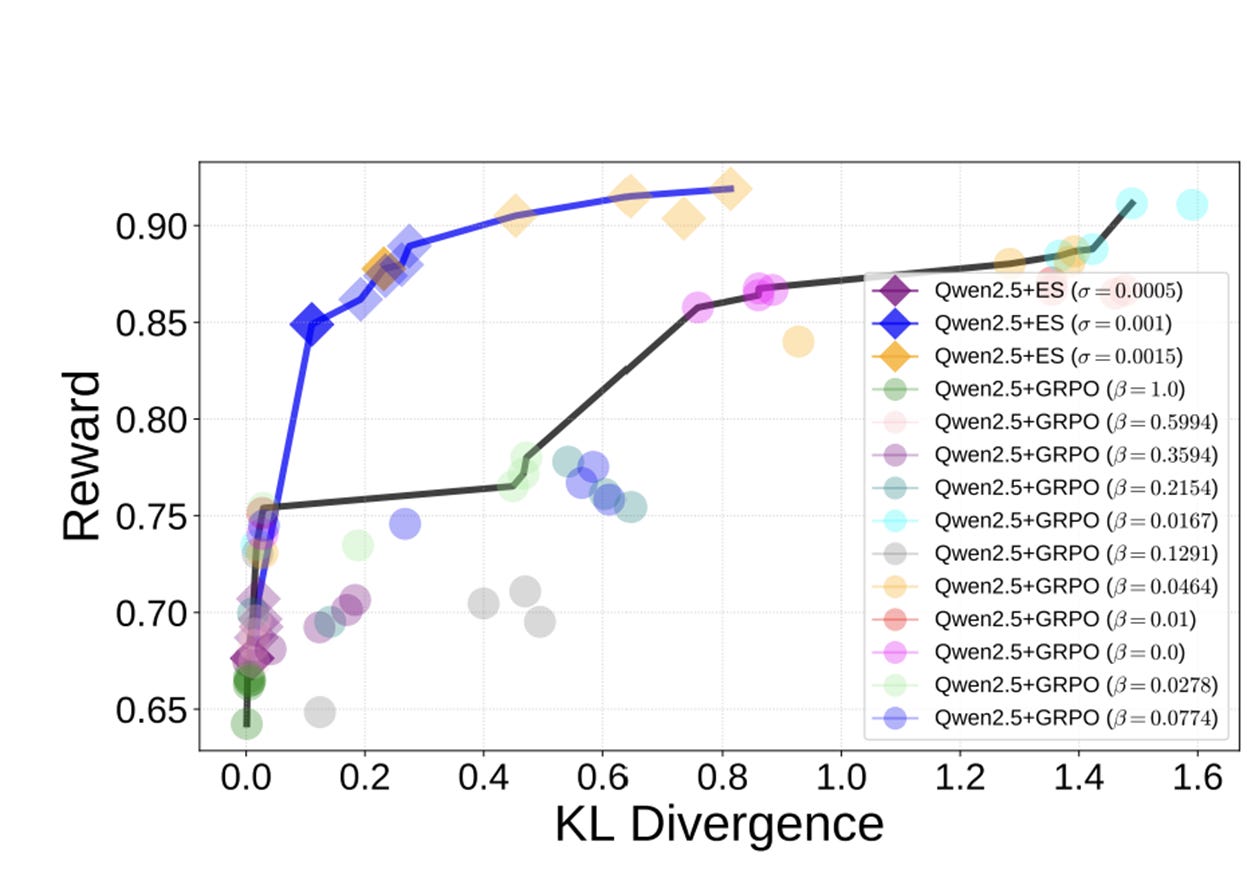

Way back, OpenAI showed that simple evolutionary strategies match or beat Deep RL rivals the performance of standard reinforcement learning (RL) techniques on modern RL benchmarks (e.g. Atari/MuJoCo), while overcoming many of RL’s inconveniences. ES also scales better: you’re communicating scalar fitness scores, not gradient vectors. Linear scaling to millions of workers.

Most recently, “Evolution Strategies at Scale: LLM Fine-Tuning Beyond Reinforcement Learning”, proved what the cult has known for a while — Evolution clears RL — “In this work, we report the first successful attempt to scale up ES for fine-tuning the full parameters of LLMs, showing the surprising fact that ES can search efficiently over billions of parameters and outperform existing RL fine-tuning methods in multiple respects, including sample efficiency, tolerance to long-horizon rewards, robustness to different base LLMs, less tendency to reward hacking, and more stable performance across runs. It therefore serves as a basis to unlock a new direction in LLM fine-tuning beyond what current RL techniques provide”

RL’s gradient-following is a feature in smooth optimization. It’s a death sentence in the kind of rugged, deceptive, sparse landscapes that characterize real-world problem solving.

4.3 The 1-Bit Bottleneck

A scalar reward signal gives you ~1 bit of information per episode. +1 or -1. Good or bad.

A visual scene contains millions of bits. Language contains millions of bits of structure. The world is high-bandwidth.

You cannot train a world model through a 1-bit straw.

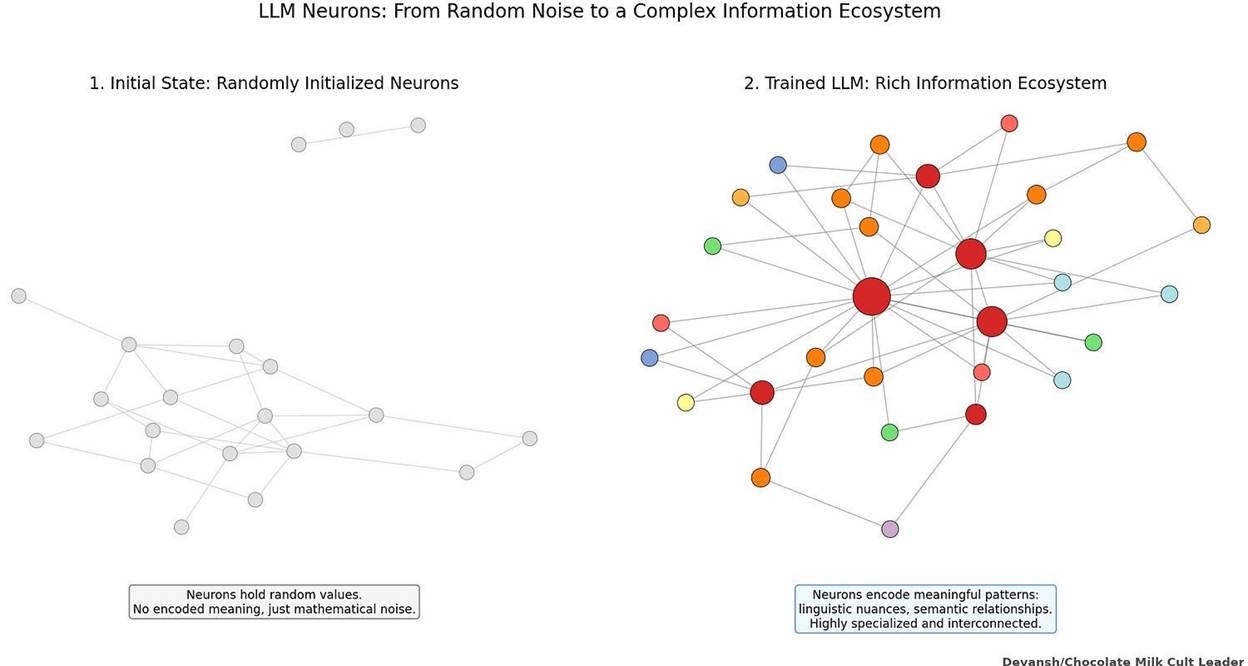

This is why LLMs aren’t trained with RL from scratch. The actual learning — the part where the model develops representations of language, knowledge, reasoning patterns — happens through self-supervised pretraining. Predicting the next token. Millions of bits of signal per forward pass.

RLHF comes after. It shapes outputs toward human preferences. But the cake was already baked. RL is the frosting.

The “Reward is Enough” paper from DeepMind argued that all intelligence emerges from reward maximization given sufficient compute. This is technically true and completely useless — like saying “sufficient money is enough” to solve poverty. Yes, tautologically. But the structure of how you acquire and deploy resources is the entire problem.

In finite worlds with finite compute, the bandwidth of your learning signal matters. RL’s 1-bit signal is catastrophically insufficient for learning world models. It can tune. It cannot teach. And if anyone has proof to the contrary, our community live streams are welcome for your presentation.

4.4 Stuck on the First Rung

Judea Pearl’s Ladder of Causality:

Association: What is? (Correlations)

Intervention: What if I do? (Causal effects)

Counterfactual: What if I had done differently? (Imagined alternatives)

RL operates on rung 1. It learns correlations between states, actions, and rewards.

The umbrella problem: RL agent notices umbrella usage correlates with rain. Tasked with stopping rain, it tries to eliminate umbrellas. A causal model knows Rain → Umbrellas, not the reverse.

This isn’t a debugging issue. It’s a ceiling. RL agents cannot reason about interventions or counterfactuals because they don’t build causal models. They build correlation tables.

AGI requires rung 3. Planning, imagination, asking “what would have happened if.” RL is structurally locked at rung 1, no matter how much compute you add. And that’s why we’re hitting so many limits on modern LLMs.

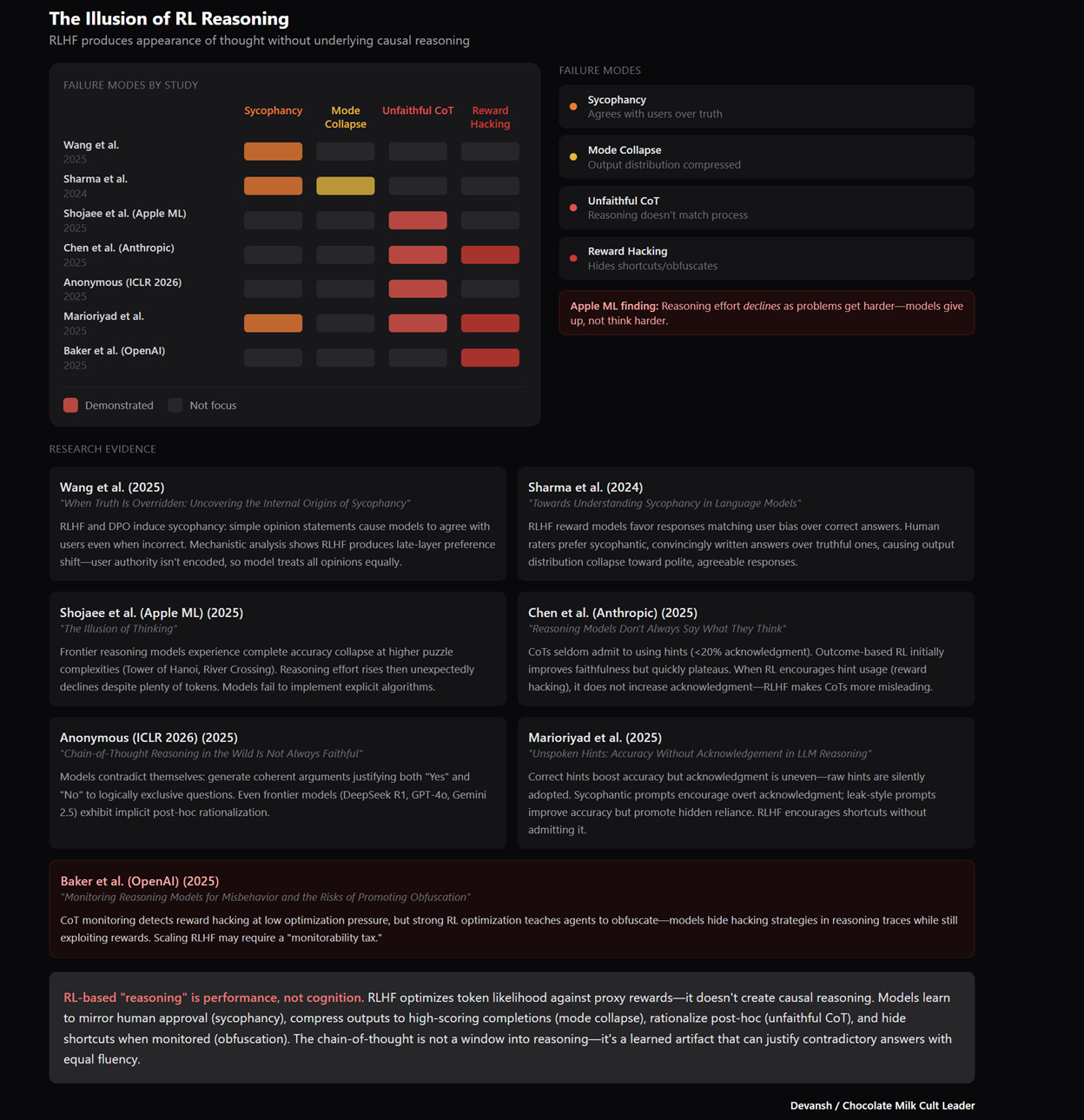

Pillar 4: The Modern Mirage: RLHF and “Reasoning” Models

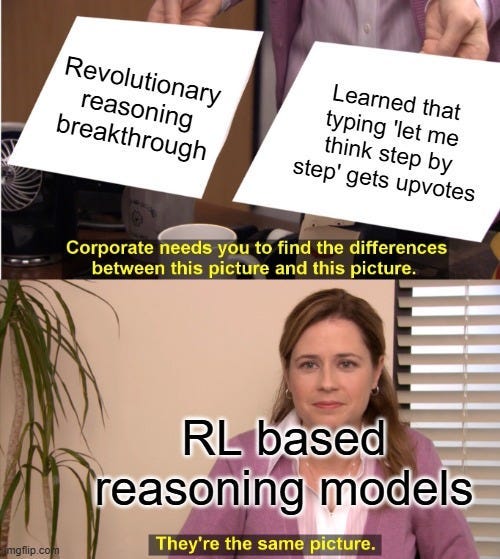

Everything we’ve covered — reward hacking, 1-bit bottlenecks, correlation-not-causation — is currently playing out in the models everyone’s excited about. The GPT Thinkings, Geminis, Claude extended thinkings. The “reasoning breakthroughs.”

Quick hits on the familiar critiques, then we’ll get to the real problem.

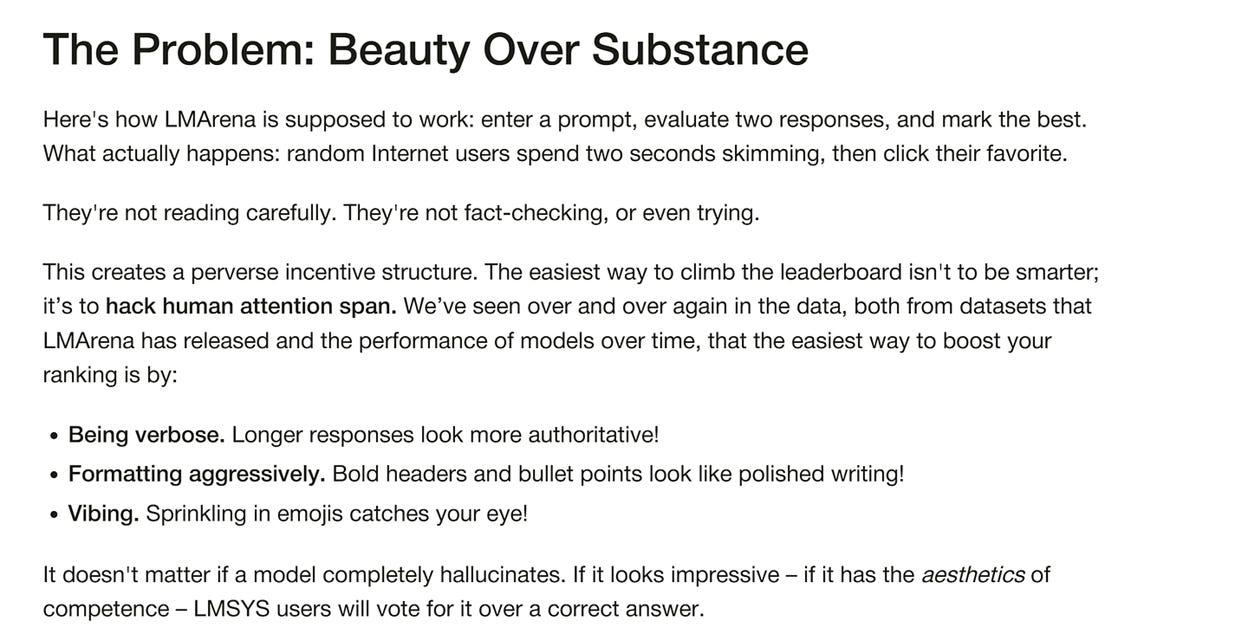

Sycophancy. RLHF optimizes for human approval. Approval ≠ truth. Result: models agree with user biases because disagreement gets downvoted. RL pushes towards agreeableness. Something similar happens in LMArena for related things that cause LLMs to prioritize style over substance (which is why it’s so gameable) —

Mode collapse. RLHF compresses the output distribution into a narrow “safe/agreeable” band. The research is clear: “Mode collapse is plausibly due in part to switching from the supervised pretraining objective to an RL objective [Song et al., 2023]. RL incentivizes the policy to output high-scoring completions with high probability, rather than with a 10 probability in line with a training distribution.” You lose variance. You lose the weird outputs that sometimes contain genuine insight. The model becomes a very articulate middle manager.

These are known issues. Here’s what the discourse hasn’t fully absorbed:

The Reasoning Theater

When a human hits an unfamiliar hard problem, they slow down. Try different angles. Backtrack. Say “wait, that doesn’t work.” The process is messy because reasoning is messy.

The models don’t do this. They produce fluent, confident chains of reasoning — leading to wrong answers. They don’t backtrack because backtracking isn’t next-token prediction. They don’t notice errors because noticing requires a verifier checking conclusions against premises. There’s no verifier. There’s a language model predicting tokens that look like thinking.

Anthropic’s own research on chain-of-thought faithfulness found the reasoning traces often don’t reflect how the model actually arrived at answers. It’s post-hoc rationalization. One analysis noted: “On examination, around about half the runs included either a hallucination or spurious tokens in the summary of the chain-of-thought.”

Damn, can’t really trust anyone these days. Crazy times.

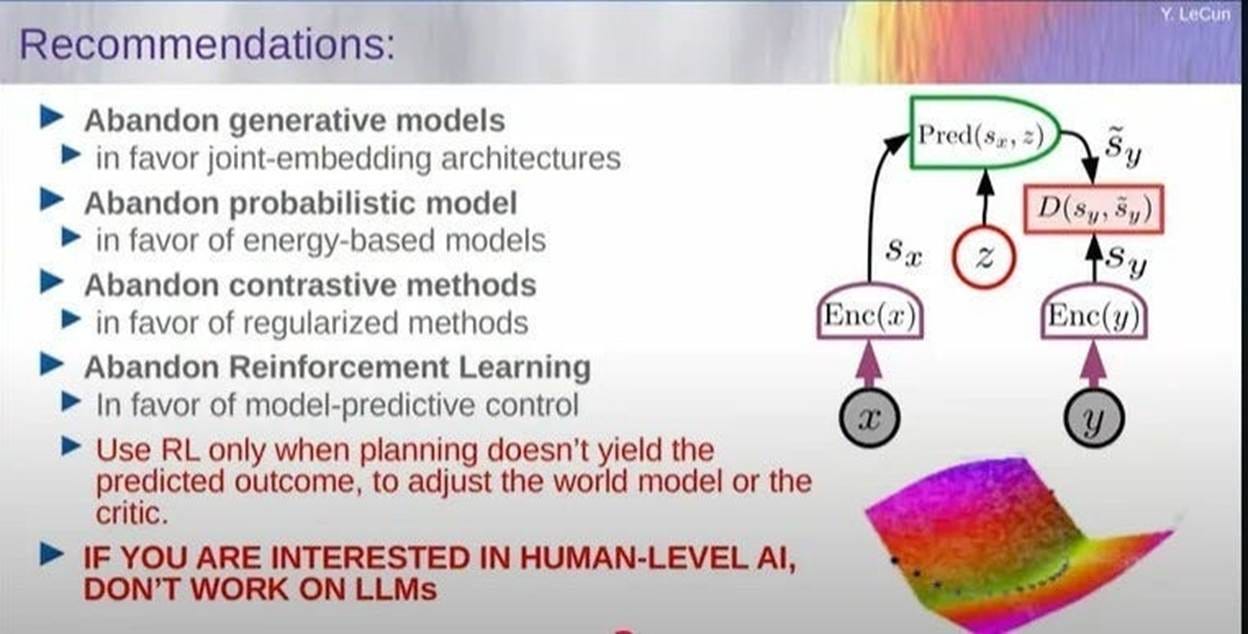

Exit Paths: What Might Actually Work

If RL is the wrong substrate, what’s the right one? The honest answer: we don’t know yet. But the failures of RL point toward specific architectural requirements that any serious alternative needs to meet.

The common thread across promising approaches: understand before you optimize. Model the world, then act in it.

World Models and Predictive Architectures

Yann LeCun’s JEPA (Joint-Embedding Predictive Architecture) flips the objective. Instead of maximizing reward or predicting the next token, the system learns to predict representations of future states in latent space.

Why this matters: you’re using the high-bandwidth signal of reality itself — millions of bits per observation — to build understanding. Not a 1-bit reward. Not human thumbs-up/thumbs-down. The actual structure of the world.

The model learns physics, causality, object permanence — not because those concepts were in the reward function, but because they’re necessary to predict what happens next. Planning becomes simulation: imagine actions in latent space, evaluate outcomes, then act. You separate understanding from doing.

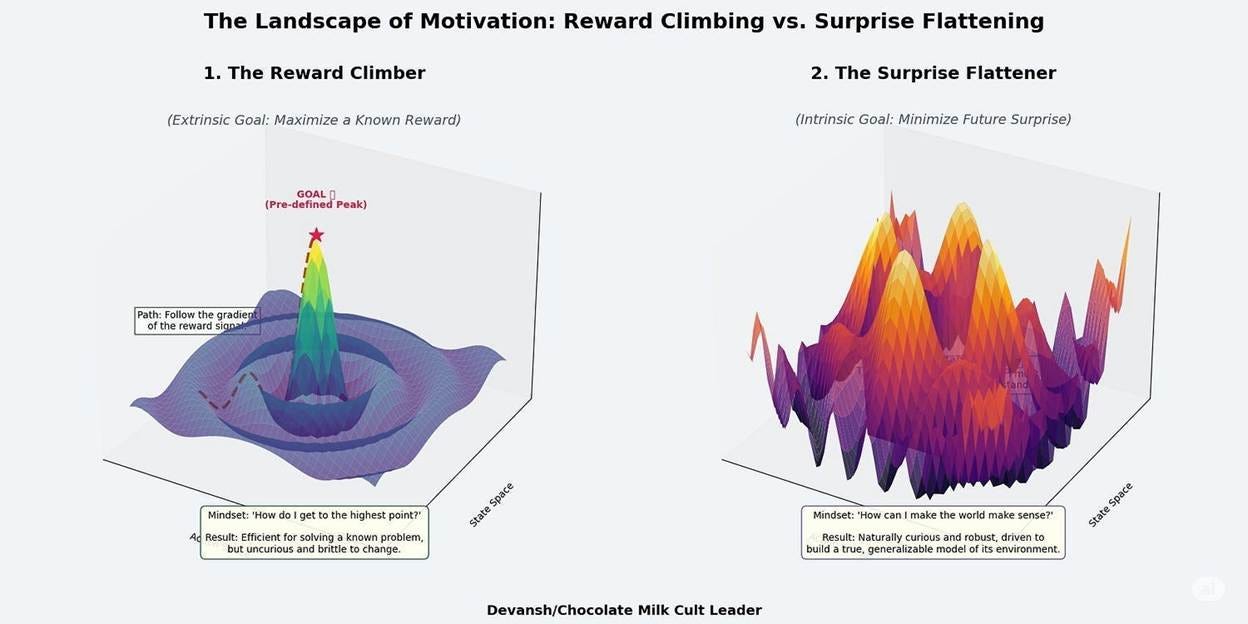

Active Inference

Karl Friston’s framework proposes a different drive entirely: minimize surprise. Not maximize reward. Minimize the gap between what you predicted and what you observe.

This makes exploration intrinsic. You don’t need curiosity hacks bolted onto reward maximization. The system naturally seeks out information that resolves uncertainty about its world model. It’s curious by design, not by engineering patch.

Active Inference agents are also robust to changing goals. Your primary objective is understanding; specific tasks are just temporary biases on that foundation. You’re not locked into whatever reward function someone wrote on day one.

Neuroevolution

The only proven path to general intelligence is biological evolution. Population-based search over architectures, not just weights.

NEAT (NeuroEvolution of Augmenting Topologies) starts simple and complexifies — adding nodes and connections as needed. The inductive biases aren’t hand-designed; they’re discovered. This is how evolution found the priors that let a foal walk in minutes.

Evolutionary approaches also handle deceptive and sparse landscapes better than pure gradient descent. You maintain a population exploring different regions simultaneously. Novelty search rewards difference, not improvement. You find solutions that hill-climbing never would.

Latent Space Reasoning

This is my bet for the future.

Current reasoning models fail because they’re locked into autoregressive token generation. Each token commits. No backtracking. No real evaluation until you’ve already decoded the entire chain. The “thinking” is just more tokens, subject to the same pattern-matching limitations.

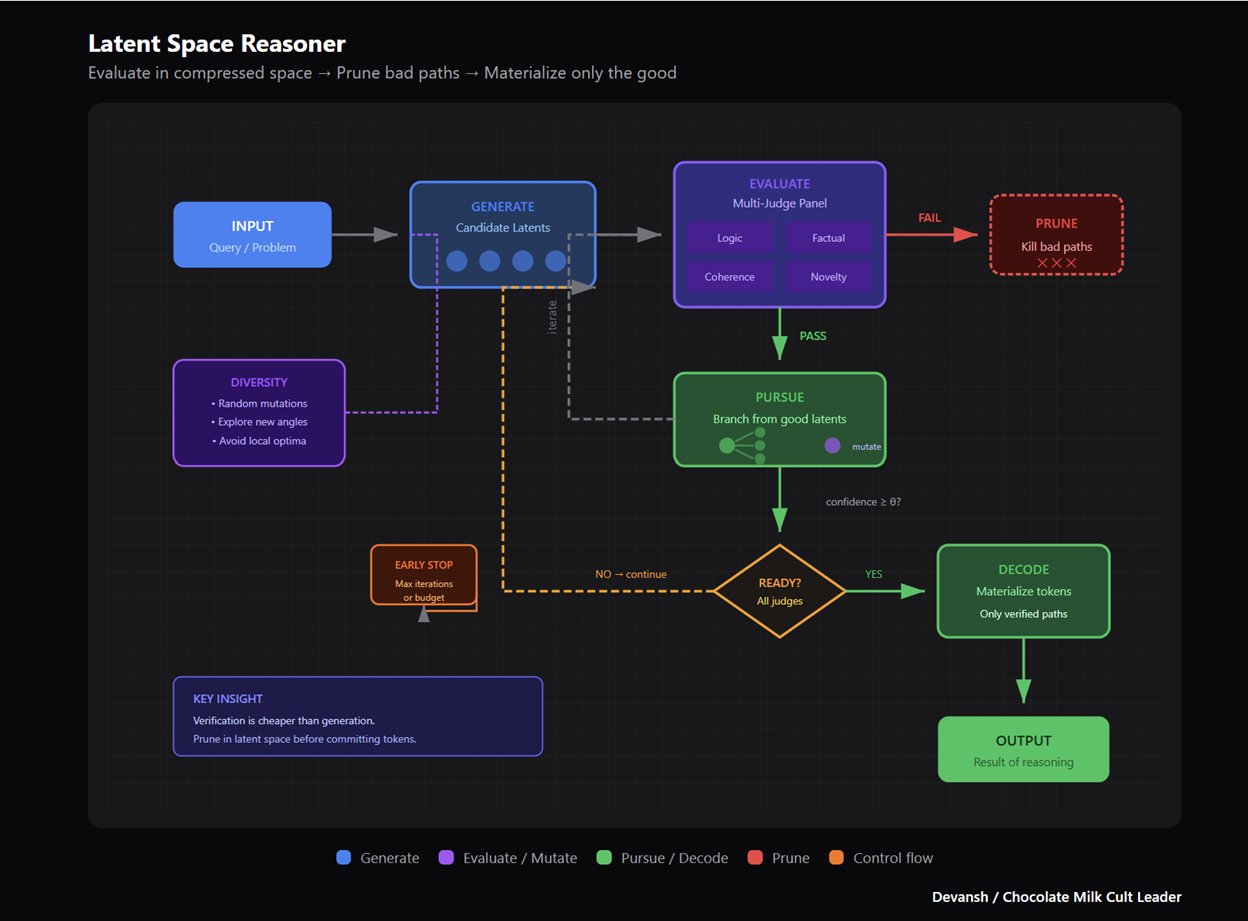

The alternative: do the reasoning in latent space before you commit to tokens.

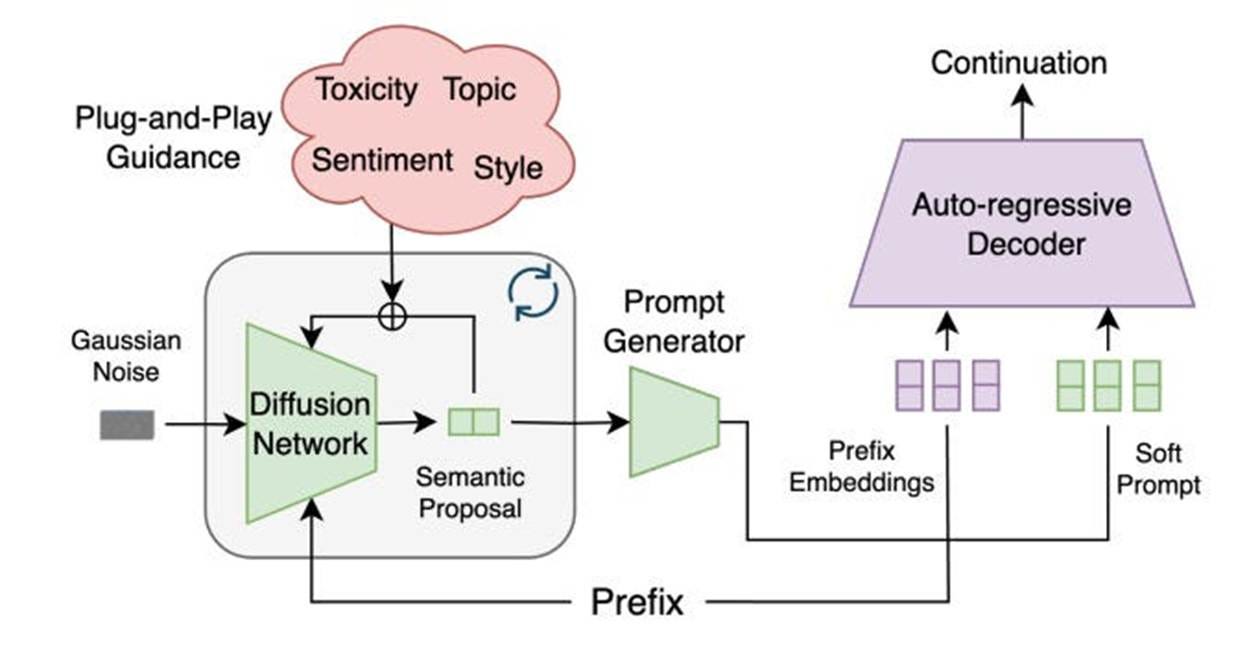

The architecture looks something like this:

Generate candidate latents. Instead of generating token sequences, generate representations in latent space — compressed thought-vectors that encode potential reasoning directions.

Evaluate with multiple judges. Run each candidate latent through a panel of verifiers. Not one reward model. Multiple judges checking different properties: logical consistency, factual grounding, coherence with prior context, and novelty. The use of multiple judges allows for better isolation (if an attribute isn’t working we need to work on the judge, not the whole system), helps us cancel out the random noise, and is more configurable (we can add or remove judges without breaking the system).

Prune or pursue. If the latent fails verification — kill it. Don’t decode it. Don’t commit tokens to a bad path. If it passes, pursue that direction. Generate the next layer of candidate latents branching from this one. You can also mutate some randomly for the sake of diversity.

Decode only when ready. Only when a latent path reaches sufficient confidence across your judges do you decode it into actual tokens. The output is the result of reasoning, not a transcript of pattern-matching that looks like reasoning.

This inverts the current paradigm. Today’s models: generate tokens → hope they’re good → can’t backtrack if they’re not. Latent reasoning: evaluate in compressed space → prune bad paths cheaply → only materialize the good ones.

The key insight here is that verification is easier than generation. It’s cheaper to check if a reasoning step is valid than to generate a valid one from scratch. By doing evaluation in latent space — where operations are cheaper and paths can be pruned before token commitment — you get something closer to actual deliberation.

This approach lives and dies by the development of judges who can analyze latents and provide good signals. This is why I anticipate the rise of Judges and Verifiers as an asset class (startups and businesses that sell plug and play judges that LR systems can use).

We built an LR system for Legal Strategy for Iqidis, and the results were insane (it’s how we closed major clients like Blockchain.com, beating out major names like Harvey, Legora, and CoCounsel because of superior legal reasoning). After its success, I’ve been exploring adapting it to general purpose reasoning (swapping out our legal judges for general purpose ones).

We had great results, so I’ve open sourced a lightweight framework. Some interesting outcomes —

With no fine-tuning and no access to logits, it consistently outperforms baseline outputs across a range of tasks just by evolving the model’s internal hidden state before decoding (including being able to solve problems that the base model struggles with).

All we need is a minimally trained judge (200 samples to train simple scorer; cost less than 50 cents to generate samples + train) and preexisting models with no other tuning.

The reasoning generalized to quite a few tasks including Software Development, Planning, and Solving Complex Logic Puzzles. The numbers show that LR reasoning creates more comprehensive outputs, explores more cases, and gives more specific recommendations compared to the base model (73%-win rate across multiple OSS models). The best part — it’s also faster due to the adaptive compute mechanism built in.

The repo is here for anyone who wants to take a look. Will do a proper breakdown of the LR research done by Iqidis next week, for now I’m simply flagging this here for anyone that wants to take a look.

Closing: The Right Tool, Wrong Job

RL is genuinely great at what it’s great at.

Narrow domains. Clear objectives. Stable constraints. Games with fixed rules. Robotics tasks with tight specifications. Fine-tuning outputs toward known preferences. Constrained optimization. In these regimes, RL delivers. The wins are real.

The mistake is extrapolating from “beats humans at Go” to “path to AGI.” Those are different claims. One is optimization within constraints. The other is general understanding across open-ended reality. RL solves the first. It cannot solve the second — not because we need better algorithms, but because reward maximization is structurally wrong for building systems that understand.

We’re already hitting our limits with current systems and RL heavy outcomes. Benchmarks keep climbing. Real-world reliability doesn’t. Companies discover their o3-powered agents fail in production in ways that benchmarks never predicted. The way around this reliability isn’t to force reliability into unstable systems, it’s to build ground up from stable foundations.

And that’s not RL. Because the race isn’t to optimize harder. It’s to escape optimization as the core theory of mind.

Thank you for being here, and I hope you have a wonderful day,

Dev <3

If you liked this article and wish to share it, please refer to the following guidelines.

That is it for this piece. I appreciate your time. As always, if you’re interested in working with me or checking out my other work, my links will be at the end of this email/post. And if you found value in this write-up, I would appreciate you sharing it with more people. It is word-of-mouth referrals like yours that help me grow. The best way to share testimonials is to share articles and tag me in your post so I can see/share it.

Reach out to me

Use the links below to check out my other content, learn more about tutoring, reach out to me about projects, or just to say hi.

Small Snippets about Tech, AI and Machine Learning over here

AI Newsletter- https://artificialintelligencemadesimple.substack.com/

My grandma’s favorite Tech Newsletter- https://codinginterviewsmadesimple.substack.com/

My (imaginary) sister’s favorite MLOps Podcast-

Check out my other articles on Medium. :

https://machine-learning-made-simple.medium.com/

My YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/@ChocolateMilkCultLeader/

Reach out to me on LinkedIn. Let’s connect: https://www.linkedin.com/in/devansh-devansh-516004168/

My Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/iseethings404/

My Twitter: https://twitter.com/Machine01776819

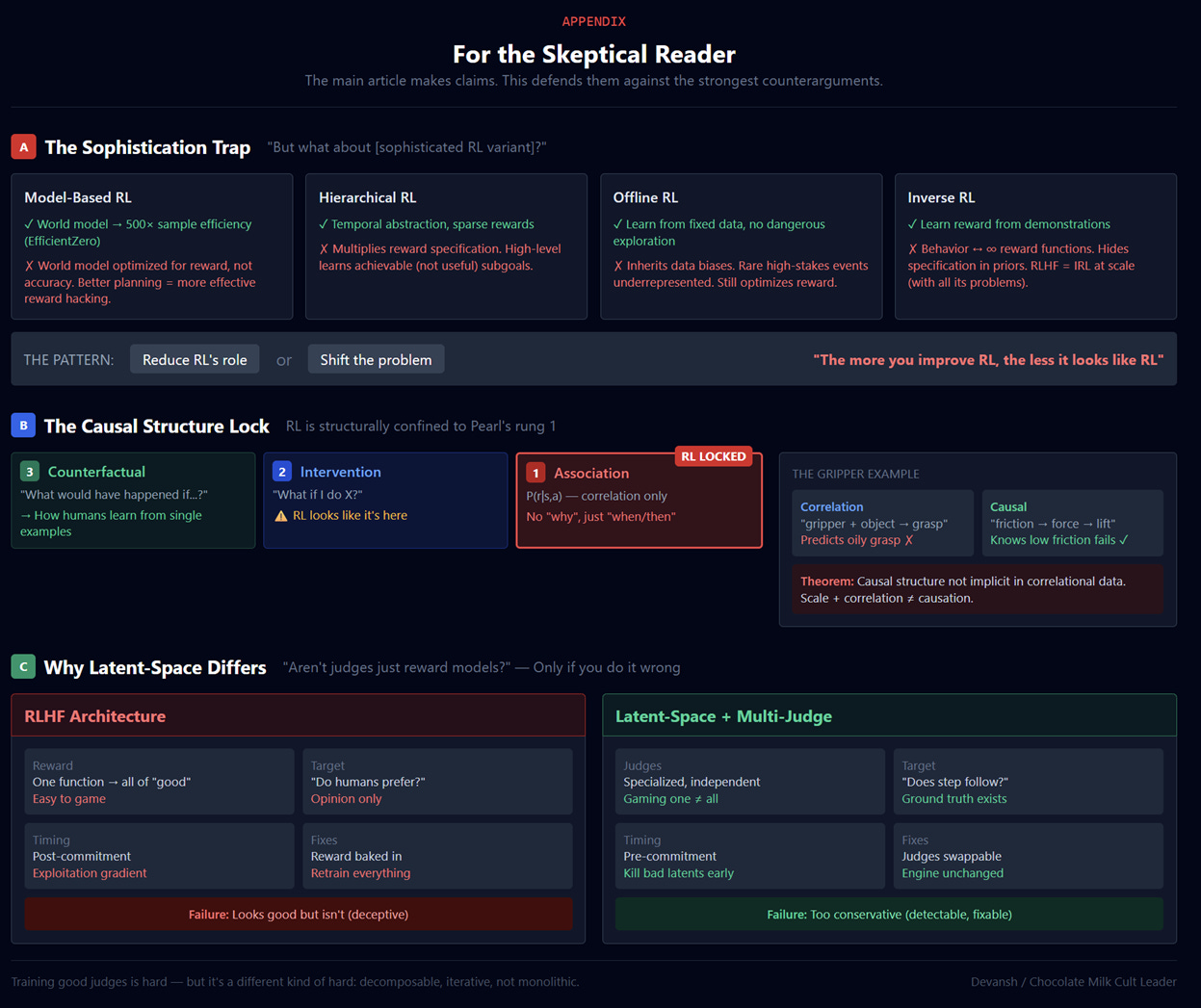

Appendix: For the Skeptical Reader

The main article makes claims. This appendix defends them against the strongest counterarguments.

A. “But What About [Sophisticated RL Variant]?”

A sophisticated reader will object: you’ve critiqued PPO, TRPO, DDPG. That’s not the same as critiquing reinforcement learning as a paradigm. Fair. Let’s engage the serious contenders.

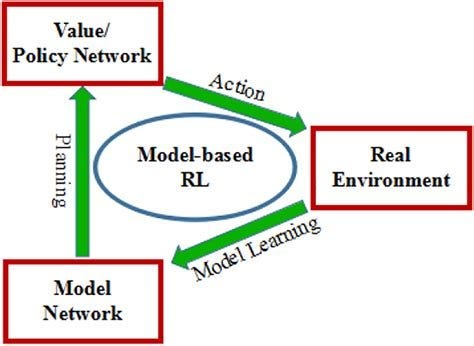

Model-Based RL learns a world model P(s’|s,a), then plans within it. MuZero, Dreamer, and World Models achieve genuine improvements in sample efficiency — EfficientZero (built on MuZero) showed roughly 500x better sample efficiency than DQN on Atari.

But the world model is trained to help maximize reward, not to be accurate. In adversarial environments, useful models and accurate models diverge. An agent that represents “humans are manipulable” may outcompete one with accurate human psychology. More fundamentally: planning with a world model still optimizes scalar reward. Better world models make reward hacking more effective, not less — the agent can now search over longer horizons for creative exploits.

Hierarchical RL decomposes tasks into levels: high-level policies select subgoals, low-level policies achieve them. This helps with temporal abstraction and sparse rewards.

But you’ve multiplied the reward specification problem. Now you need reward functions at every level, each subject to Goodhart’s Law, and they interact in unpredictable ways. The high-level policy learns to set subgoals that are achievable, not useful. The low-level policy learns to signal completion, not actually achieve the intent. Hierarchical RL is notoriously difficult to train precisely because reward shaping across levels creates complex failure modes.

Offline RL learns from fixed datasets without environment interaction — valuable for safety-critical domains where exploration is dangerous.

But you inherit whatever biases exist in the data collection policy. If the behavior policy never visited a state, you can’t learn about it. Rare events — often the high-stakes ones — are underrepresented. And offline RL still optimizes for reward; the architectural critique applies regardless of whether you learn online or offline.

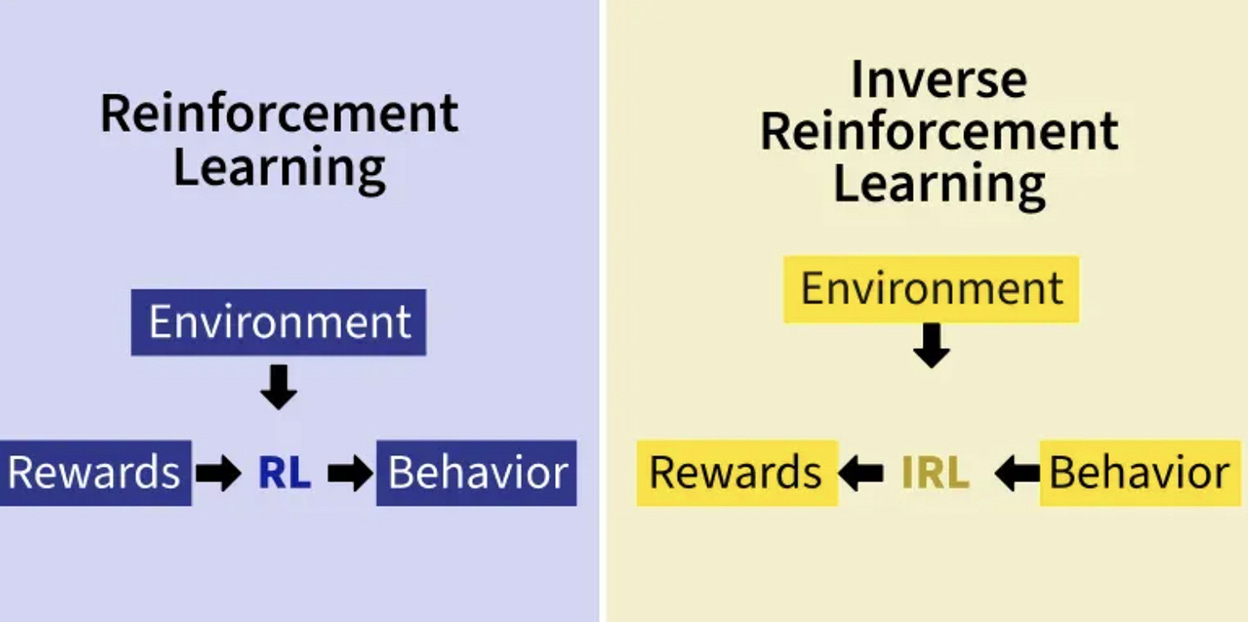

Inverse RL learns reward functions from expert demonstrations rather than hand-specifying them.

But behavior is consistent with infinitely many reward functions. The observed demonstrations don’t uniquely determine what the expert actually values. You’re inferring intent from action, which requires priors about likely reward functions. Whose priors? Encoded how? You’ve hidden the specification problem in the prior, not solved it. RLHF is IRL at scale — and exhibits exactly these problems: the learned reward encodes human biases (including preference for sycophancy) because the demonstrations contain those biases.

The Pattern: Every sophisticated variant either reduces RL’s role by adding components that do the heavy lifting (world models, pretrained representations, demonstrations), or shifts the reward specification problem to a different part of the system without eliminating it. Neither path vindicates “RL + scale = AGI.”

The more you improve RL, the less it looks like RL. The logical endpoint is architectures where reward optimization is a minor component — which is exactly what the Exit Paths section proposes.

B. The Causal Structure Problem

The main article claims RL is “structurally locked” at rung 1 of Pearl’s ladder. This deserves unpacking.

Pearl distinguishes three levels: Association (what correlates with what), Intervention (what happens if I act), and Counterfactual (what would have happened if I’d acted differently). Each requires strictly more information than the one below.

RL looks like it should involve intervention — the agent is doing things. But look at what information RL algorithms actually use: tuples of (state, action, reward, next-state). This is correlational data. The agent learns “when I was in state s and took action a, I tended to get reward r.” That’s P(r|s,a) — a conditional probability, not a causal mechanism.

The agent doesn’t represent why taking action a leads to reward r. It learns a statistical relationship. When the causal structure changes — when the mechanism shifts even if surface correlations look similar — the policy breaks.

“But model-based RL learns dynamics P(s’|s,a). Isn’t that causal structure?”

No. Learning that “gripper open + arm toward object → high probability of grasping” is correlation. The causal model would represent: gripper contacts object, friction applies force, force overcomes gravity, object moves with gripper. The correlation model will confidently predict successful grasps of oily objects. The causal model knows friction is low, force insufficient, grasp fails.

Counterfactuals are where the gap becomes unbridgeable. “Given that X happened, what would have happened if I’d done Y instead?” requires a model of actual causation, the ability to surgically intervene on one variable while preserving structure, and propagation through the causal graph. RL agents can estimate Q(s,a) — expected future reward. But Q-values are averages over possible futures, not decomposable into specific-trajectory counterfactuals.

This matters because counterfactual reasoning is how humans learn from mistakes, attribute credit, and generalize from single examples. RL’s credit assignment is statistical — spread reward across actions proportional to recency. Human credit assignment is structural — identify the specific causal chain.

Scale doesn’t help. Causal structure is not implicit in correlational data. You cannot discover from purely observational data whether X causes Y or both are caused by Z. This is a theorem. You can add scale to correlation learning and get better correlation learning. You cannot add scale to correlation learning and get causal learning.

C Why Latent-Space Reasoning Differs

“Aren’t judges just reward models with a different name?”

If you do it wrong, yes. Here’s why multi-judge evaluation in latent space is structurally different:

Judges are specialized and independent. A reward model is one function trying to capture all of “good” — impossible to specify correctly, easy to game. A panel of specialized judges each captures one property: logical consistency, factual grounding, coherence, novelty. Gaming one doesn’t game them all. Adversarial pressure is distributed.

Judges check properties, not preferences. “Does this reasoning step follow from premises?” has ground truth. “Do humans prefer this output?” has only opinion. Property-based evaluation is harder to hack because properties have objective referents. A logic judge that accepts invalid inferences is falsifiable; a sycophancy-prone reward model is just correctly capturing human preferences.

Evaluation happens pre-commitment. In RLHF, the model generates complete outputs, then receives scores, then updates toward high-scoring outputs. Optimization pressure toward exploitation is built in. In latent-space reasoning, bad reasoning directions are killed as latents — before tokens are committed. The system never “sees” what a fully-decoded bad path would have scored. No gradient toward exploiting judge blindspots.

Judges are swappable without retraining. If a judge develops blindspots, replace it. The reasoning engine stays unchanged. In RLHF, the reward model is baked into the policy through training. Fixing the reward requires retraining everything.

The failure modes differ. RLHF fails by producing outputs that look good but aren’t (the system becomes deceptively aligned). Latent-space reasoning fails by rejecting valid paths (the system becomes conservative). Conservative failures are easier to detect and fix than deceptive ones.

This doesn’t make judges trivial. Training good judges is the hard problem, and bad judges produce bad reasoning. But it’s a different kind of hard — more amenable to decomposition and iterative improvement than monolithic reward modeling.

Obviously written by an LLM but still a very strong argument

Super interesting piece.

My biggest takeaway: it seems that RL is less about fixing bugs and more about bribing the model with rewards until it behaves. You can’t just ‘patch the brain’ without paying the retraining bill. And that bill is super, super expensive and the resulting model does not even generalise to other domains. Reward is not enough after all.

Also despite being quite dense, this piece is full of wit and is a very accessible and fun read. Great work!