Why Open Source AI is Suddenly Raising Hundreds of Millions of Dollars

Databricks, Sakana AI, Radix, and why Investors are rushing to invest in Open Source AI

It takes time to create work that’s clear, independent, and genuinely useful. If you’ve found value in this newsletter, consider becoming a paid subscriber. It helps me dive deeper into research, reach more people, stay free from ads/hidden agendas, and supports my crippling chocolate milk addiction. We run on a “pay what you can” model—so if you believe in the mission, there’s likely a plan that fits (over here).

Every subscription helps me stay independent, avoid clickbait, and focus on depth over noise, and I deeply appreciate everyone who chooses to support our cult.

PS – Supporting this work doesn’t have to come out of your pocket. If you read this as part of your professional development, you can use this email template to request reimbursement for your subscription.

Every month, the Chocolate Milk Cult reaches over a million Builders, Investors, Policy Makers, Leaders, and more. If you’d like to meet other members of our community, please fill out this contact form here (I will never sell your data nor will I make intros w/o your explicit permission)- https://forms.gle/Pi1pGLuS1FmzXoLr6

In the past few weeks, three deals landed that tell the same story from different angles.

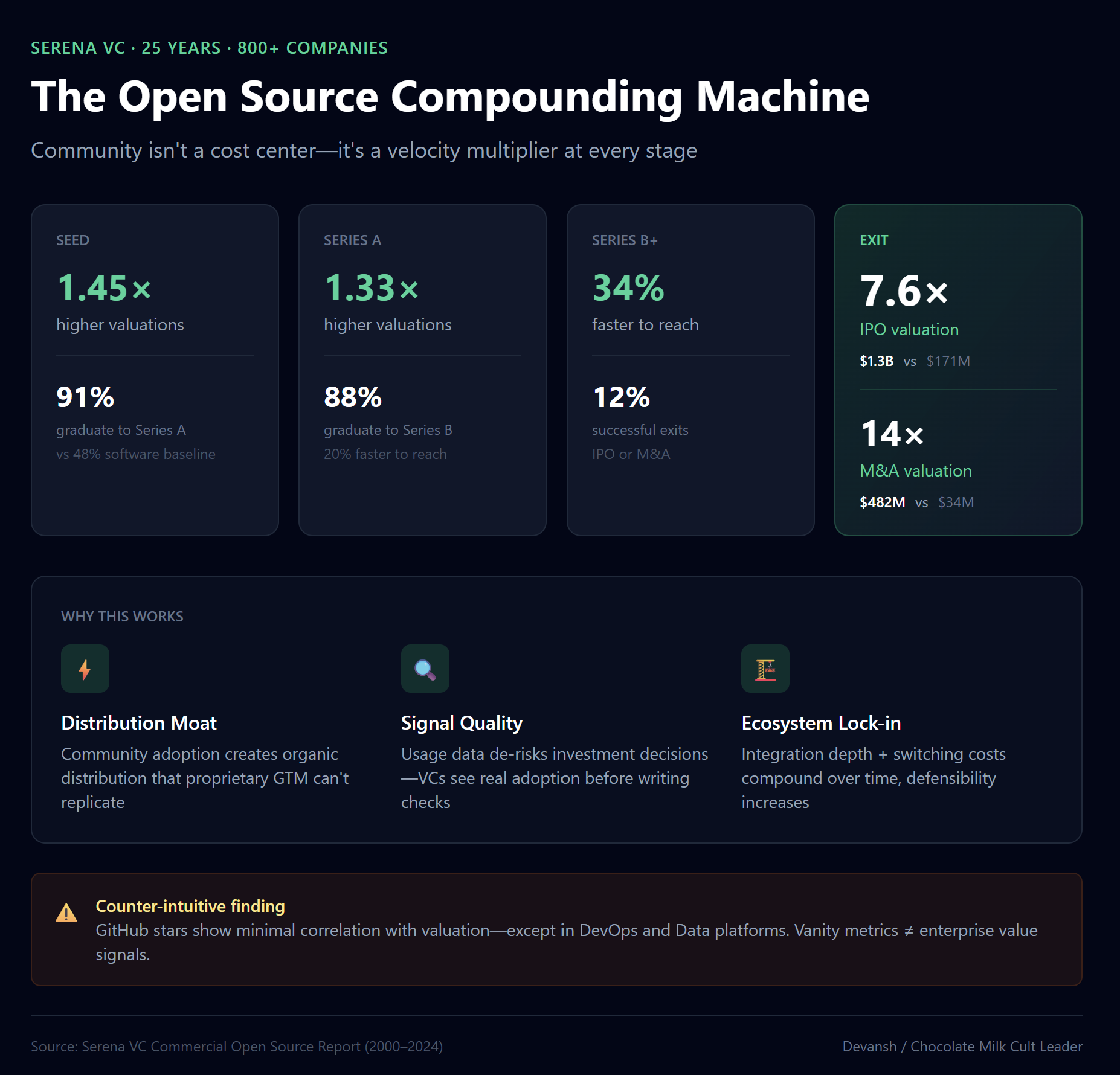

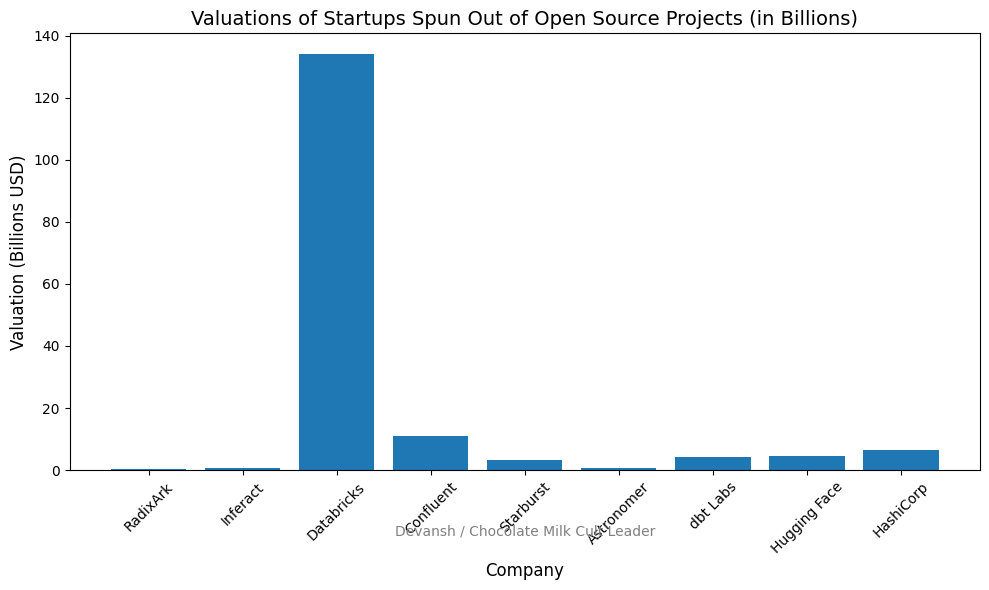

Databricks raised another $4 billion at a $134 billion valuation — its third major raise in under a year. The company that started as an open-source project from Berkeley now commands a valuation that puts it alongside the most valuable private companies in tech. Ion Stoica, co-founder, built the original playbook: release Spark as open source, let it become infrastructure, build the business on top.

Meanwhile, SGLang — an inference engine incubated at Berkeley under the same Ion Stoica — spun out as RadixArk with a $400 million valuation. No sales team. No enterprise contracts. Just GitHub commits and quiet adoption inside teams like xAI and Cursor. Accel led the round. Intel’s CEO came in as an angel.

Finally Sakana AI, a Tokyo-based research lab with no traditional product, announced a strategic partnership with Google. Google invested. Sakana gets cloud distribution. The currency wasn’t revenue — it was a string of open research releases that made their judgment legible to exactly the right people.

In today’s article we’ll look behind individual headlines to answer a deeper question: why does openness create asymmetric outcomes, and what does that mean for founders, investors, and companies deciding where to place bets?

Here’s what we’ll cover:

Why open source wins serious attention (and why “free software” misses the point)

How SGLang used open infrastructure to create dependency before incorporation

How Sakana used open research to build authority and convert it into a Google partnership

The difference between infrastructure capture and authority formation — and why confusing them is expensive

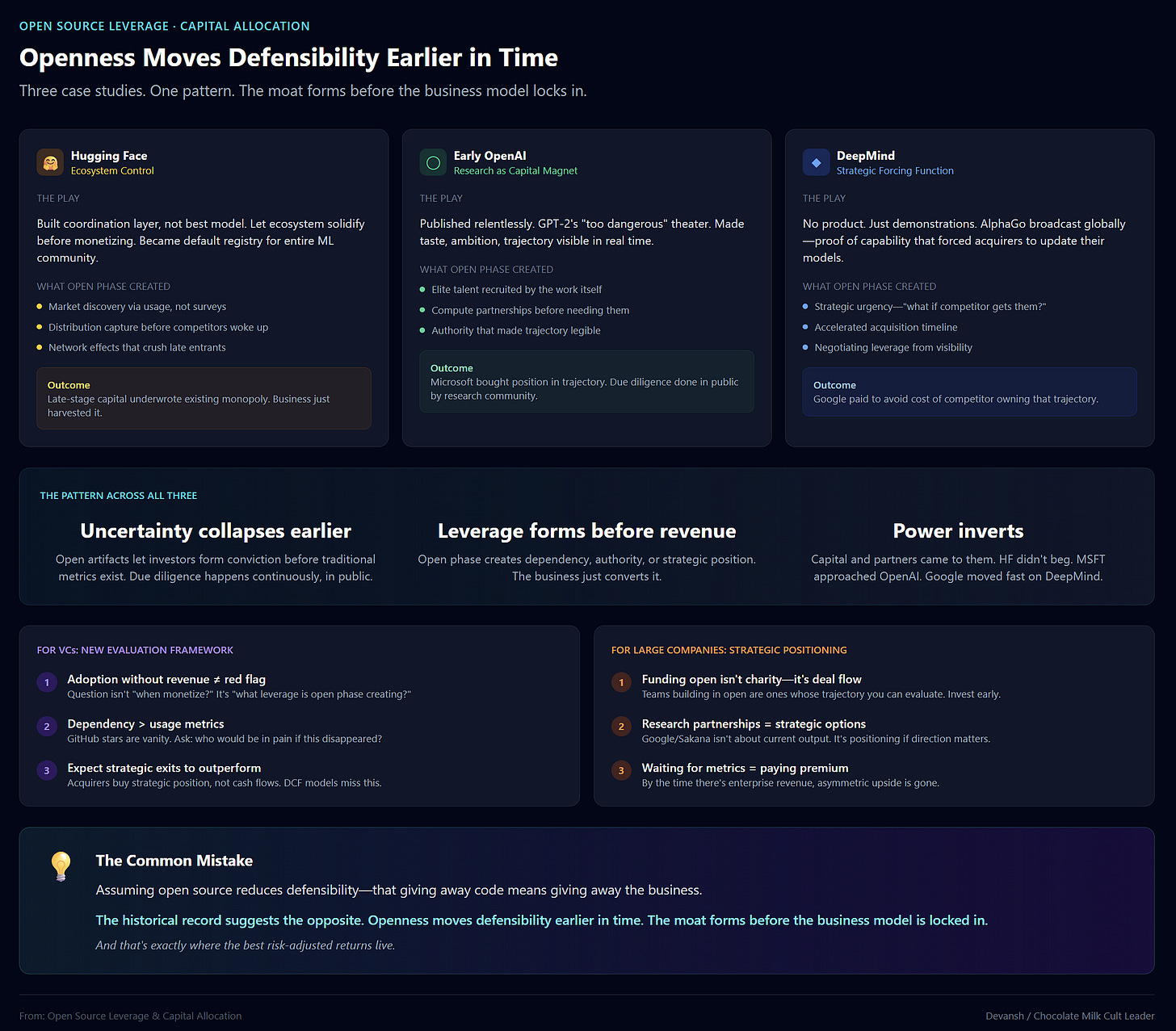

Why Hugging Face, early OpenAI, and pre-acquisition DeepMind all followed the same logic

Where open strategies fail, where they don’t, and what this means for capital allocation

Executive Highlights (TL;DR of the Article)

Open source isn’t free software. It’s a filter for serious attention — and serious attention converts into leverage before revenue exists.

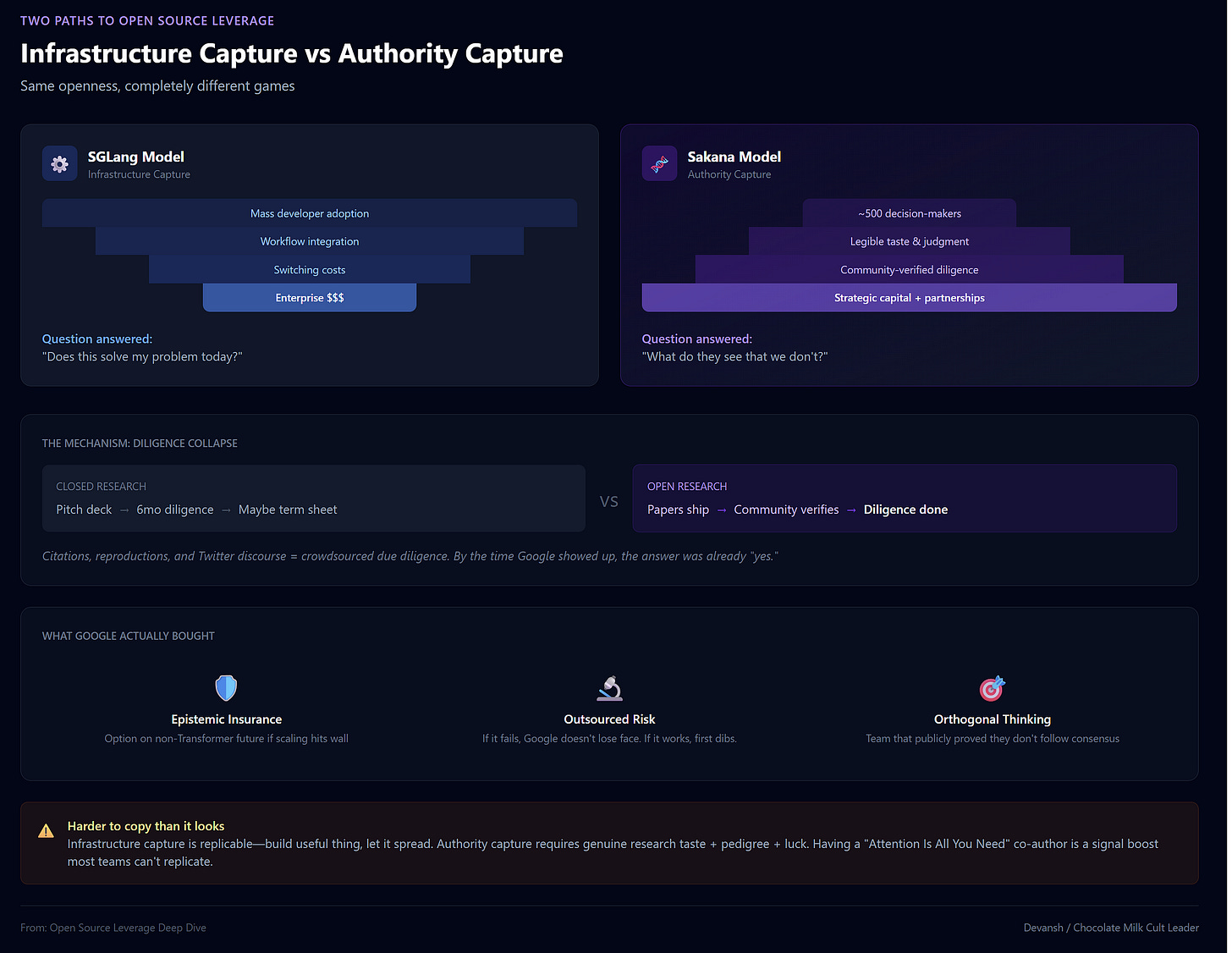

Two paths to make this work:

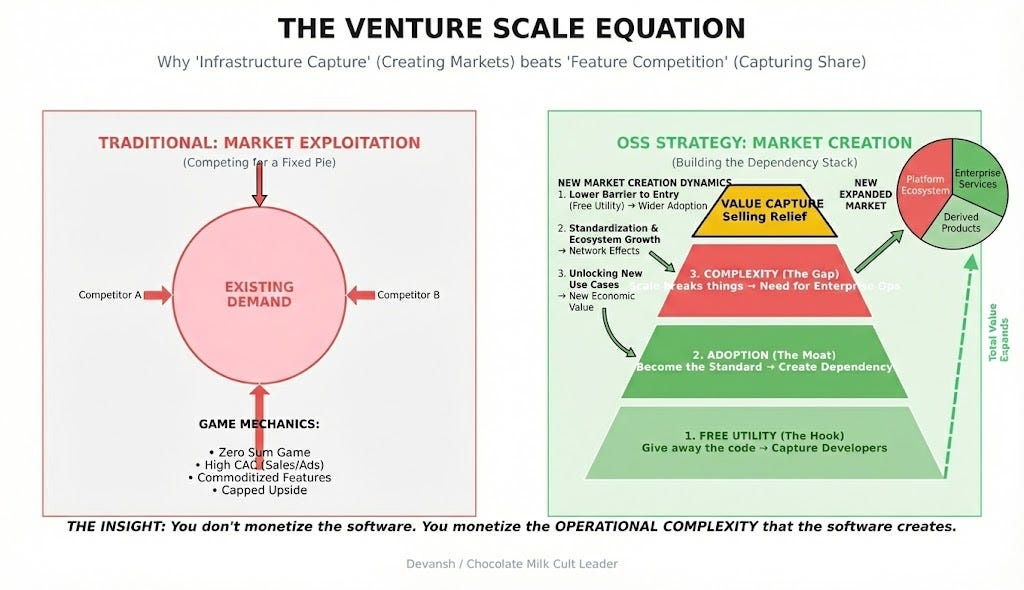

Infrastructure capture (SGLang → RadixArk): Release something useful. Let engineers adopt it without asking permission. Let adoption create dependency. Monetize the operational complexity enterprises will pay to offload. By the time you incorporate, you’re not pitching — you’re selling enterprise hardening for systems people already rely on.

Authority formation (Sakana → Google): Release research that demonstrates taste and direction. The audience isn’t users — it’s frontier labs, hyperscalers, and investors who need to identify who matters in five years. Convert credibility into partnerships and distribution that would otherwise take a decade to earn.

Both paths share the same logic: openness collapses uncertainty earlier, letting capital and partners form conviction before traditional metrics exist. Databricks, Hugging Face, early OpenAI, pre-acquisition DeepMind — same pattern, different eras.

For founders: Pick one path. Commit. Don’t blend signals.

For investors: The best open-source opportunities won’t look like good investments by conventional metrics. The question isn’t “when will they monetize?” — it’s “what leverage is the open phase creating?”

For large companies: Teams building in the open are showing you their cards. The cost of waiting for traditional metrics is paying strategic premiums for positions you could have secured earlier.

Open strategies fail when they create attention without dependency or authority. They succeed when the artifact embeds itself in other people’s systems — or in other people’s models of the future.

I put a lot of work into writing this newsletter. To do so, I rely on you for support. If a few more people choose to become paid subscribers, the Chocolate Milk Cult can continue to provide high-quality and accessible education and opportunities to anyone who needs it. If you think this mission is worth contributing to, please consider a premium subscription. You can do so for less than the cost of a Netflix Subscription (pay what you want here).

I provide various consulting and advisory services. If you‘d like to explore how we can work together, reach out to me through any of my socials over here or reply to this email.

Every month, the Chocolate Milk Cult reaches over a million Builders, Investors, Policy Makers, Leaders, and more. If you’d like to meet other members of our community, please fill out this contact form here (I will never sell your data nor will I make intros w/o your explicit permission)- https://forms.gle/Pi1pGLuS1FmzXoLr6

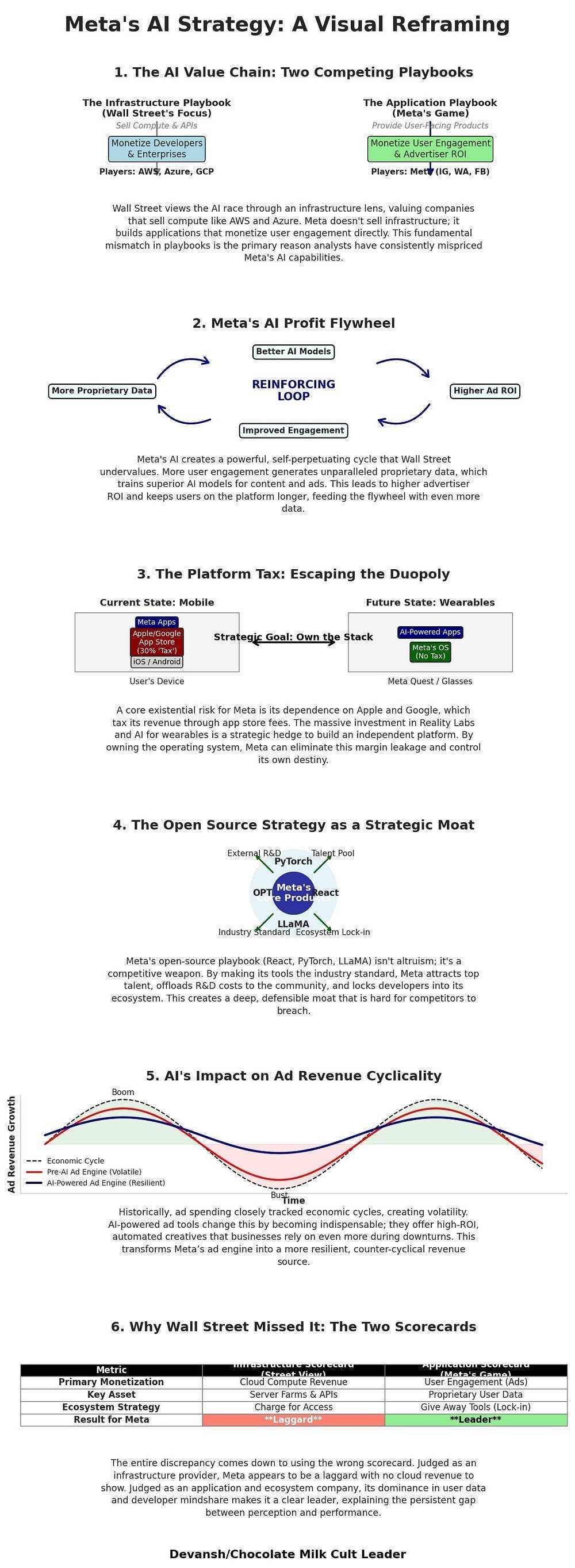

Why Open Source Quietly Wins Mindshare with Serious People

Most people think of open source as a pricing strategy — you give software away to get users, then try to charge them later. Or you use OSS to commoditize your complement, giving away powerful software in one part of the value chain so that it value and attention can flow to a layer you control (Meta gives away Llama since they’ve already developed it → people improved it → they fold those changes back in to make moderation, AI ads, and coding more effective → their AI ads make them a lot of money → profit; they also lose nothing since they were never goign to be able to sell an LLM anyway, given how much work serving inference is + how much that would distract from their business).

That’s not wrong, but it can miss what makes open source powerful for startups and other smaller players in the game. For such groups, Open Source is the AI equivalent of posting clips of your songs on TikTok/Reels to let the community find your work.

The word “mindshare” gets thrown around loosely, but in practice, there are three different kinds, and they convert to value very differently:

Public mindshare is social media, press coverage, brand recognition. Open source is not efficient here. A slick demo or viral tweet usually wins.

User mindshare is adoption, workflow integration, and daily usage. Open source can win here, but this tends to be the domain of closed products with strong distribution. Especially when considering larger enterprises, which are likely to default to incumbent brands over a better new product to minimize risk.

Expert mindshare is the attention of engineers, researchers, infrastructure architects, and investors who underwrite technical risk. This is where open source has a structural advantage that closed approaches can’t replicate.

The reason here, my loves, is simple: inspectability trumps persuasion.

Serious people — those with real technical or capital exposure — aren’t usually content with “is this popular?” They ask different questions. Can this actually work? What assumptions does it make? Where are the tradeoffs? What breaks at scale? What does this team understand that others don’t?

Open artifacts answer those questions without a meeting. A Staff Engineer evaluating dependencies can profile the kernel themselves. A Research Director assessing collaborators can read the training code. An investor underwriting technical risk can see the architecture choices. You don’t have to trust the pitch. You can look.

This matters more in AI than in most fields because uncertainty is unusually high. Models are opaque. Benchmarks are gameable. Roadmaps are speculative. In this environment, people default to a simple heuristic: if it’s real, it will show up in the work; either directly (reviewing the work) or indirectly (social proof from builders).

Seen another way, open code and open research lower the cost of taking something seriously. They let experts form conviction independently, without relying on narratives or relationships. That independence is why open projects attract unusually strong early contributors, quiet internal adoption inside good teams, and early interest from sophisticated capital.

This is also why open strategies feel uncomfortable. They expose quality early (or the lack of it). They force teams to earn attention rather than buy it. And in doing so, they make you legible to the people who matter before you have a product, revenue, or even a clear business model (or be forced to have an intimate confrontation with your own lack of skills).

Once you see open source this way — not as “free,” not as “marketing,” but as a filter for serious attention — a deeper pattern becomes visible. Some teams use openness to become infrastructure defaults. Others use it to build research authority and strategic trust.

The first path is best understood through the story of SGLang.

SGLang and RadixArk: Open Source as Infrastructure Capture

So how does the “filter for serious attention” actually convert into a business?

The cleanest path is when the open artifact doesn’t just signal quality — it becomes infrastructure. Something other people’s systems depend on. When that happens, you’ve converted expert attention into structural leverage.

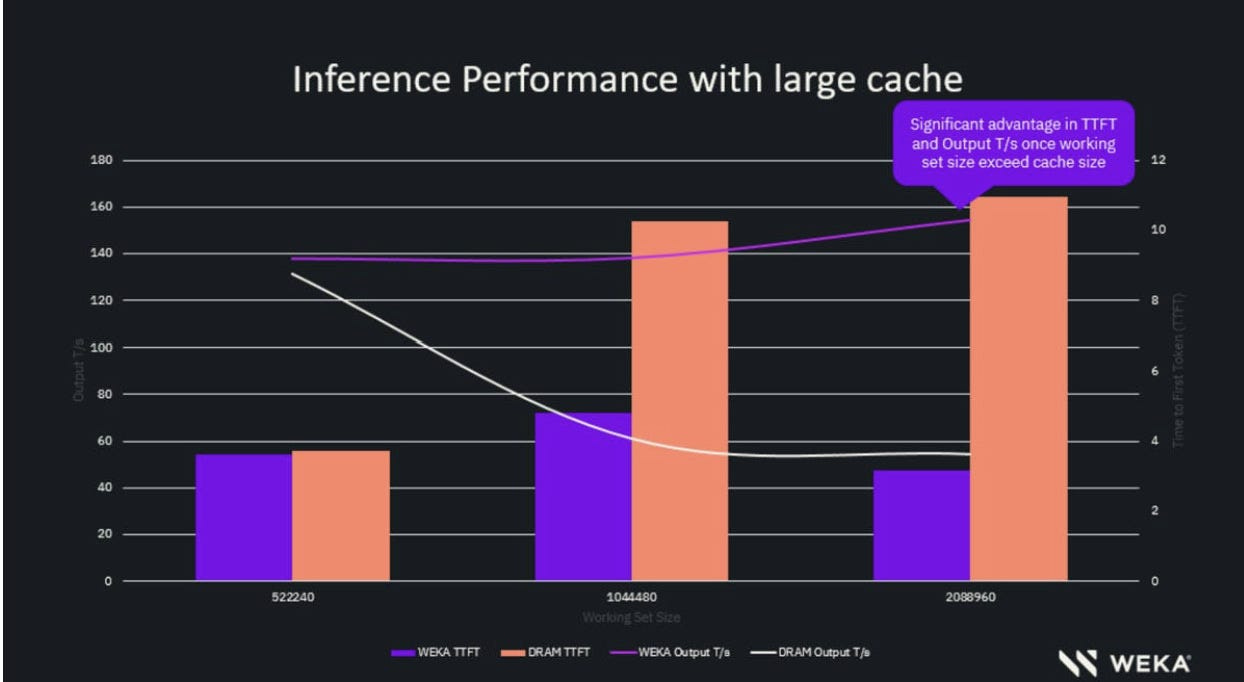

SGLang, one of the inspirations for this article, is the clearest example of this playing out. To understand why it mattered, you need to understand why inference became the problem everyone is scrambling to solve, and why everything always comes down to KV caches.

Training a frontier model is a one-time capital expenditure. Brutal, but finite. You spend hundreds of millions on compute, run the job, and you have a model. Inference is different. Inference is operational expenditure that scales with usage. Every query, every API call, every agent loop burns compute. As AI moves from demos to production, inference costs don’t just grow — they compound.

The historical approach to inference optimization was vendor lock-in. NVIDIA gives you TensorRT. Cloud providers give you proprietary serving stacks. These work, but they come with constraints: opacity, limited customization, and the kind of dependency that makes infrastructure teams nervous. You’re trusting a black box with your most latency-sensitive, cost-sensitive workloads.

SGLang emerged from Lianmin Zheng’s work at Berkeley under Ion Stoica. The core insight was architectural: most inference engines have the memory span of a goldfish — they forget the context you just sent as soon as they answer. SGLang introduced RadixAttention, which allowed the system to reuse previous computations (the KV cache) across different calls instead of recomputing from scratch every time.

For a startup running an AI coding assistant — where users edit the same code file over and over — this isn’t a nice-to-have. It’s the difference between a profitable query and a money-losing one.

An infrastructure engineer at xAI or Cursor could clone the repo, read the scheduler logic, profile the memory allocation, and understand exactly what tradeoffs were being made. They could benchmark it against their specific workload mix, not some generic eval suite. They could modify it. They could file an issue and get a response from the actual authors.

This is how SGLang spread — not through sales, but through engineers telling other engineers. The adoption pattern wasn’t “let’s evaluate vendors” — it was “this is what the sharp teams are using, let’s look at it.” Call it Shadow IT for AI infrastructure. Staff Engineers adopted it internally, often without asking permission, because it solved a hair-on-fire problem immediately. By the time the business side got involved, SGLang was already critical infrastructure that they relied on.

That’s a fundamentally different distribution motion. And it creates a fundamentally different fundraising position.

By the time SGLang spun out as RadixArk, the hard parts were already done. Real teams had validated the approach in production. Engineers had built workflows around it — switching costs existed before any contract was signed. The GitHub stars, the contributor graph, the internal adoption at recognizable companies — all of this was legible due diligence.

So when Accel showed up, they weren’t underwriting a slide deck. They were underwriting an existing monopoly on a technical standard.

This is infrastructure capture in a nutshell: release something genuinely useful, let serious teams adopt it, let that adoption create dependency, then build a business around the operational complexity that enterprises will pay to offload. The open-source phase became the first step of market creation.

The monetization paths become obvious once you have dependency: hosted solutions, enterprise support, optimization services, and managed inference. You’re not begging people to pay you. You’re selling them the enterprise hardening and guarantees that their businesses now require for compliance and performance reasons.

That’s one path openness enables. But there’s another — one that doesn’t rely on adoption at all. It relies on authority. And it looks completely different.

Sakana AI: Open Research as Authority Capture

If SGLang is about building plumbing everyone needs, Sakana is about building a brain everyone respects.

The mechanism is completely different. SGLang needed adoption — engineers installing the package, building workflows around it, creating switching costs. Sakana didn’t need adoption. Almost no one is “using” their research in a production system. The audience wasn’t engineers solving today’s problems. It was maybe 500 people: frontier lab leadership, hyperscaler strategy teams, government science advisors, and the investors who back decade-long research bets.

For that audience, open research answers a different set of questions. Not “does this solve my problem?” but: What does this team see that others don’t? Do they have taste in problem selection? Are they working on something that matters in five years, not just what’s fashionable now?

You can’t really answer those questions with a pitch deck, now can you?

To understand why that mattered for Sakana specifically, you need to understand the strategic landscape they were betting against.

Almost everyone in frontier AI — OpenAI, Anthropic, Google, Meta — is running the same play: make the Transformer bigger, throw more compute at it, scale until something happens. This works. It’s safe so the percentage of failure is not as high (there are various political reasons behind why scaling is the safe default and why researchers in these teams trying something else will be punished).

It’s also brutally expensive and has been hitting diminishing returns.

For a company like Google, that creates a strategic risk they can’t fully hedge internally. What if the next breakthrough isn’t just scale? What if it’s a different paradigm entirely — agentic automation, evolutionary optimization, something that makes raw compute less important?

Google needs exposure to those alternative futures. But if Google rolls something out and it fails, it could be catastrophic for them. Hence, they need partners looking into the riskier aspects of research to partner with. If it works, they get first dibs. If it fails, Google avoids losing face.

That’s the problem Sakana solved (and if you’re a research lab hoping to partner with big labs, this is the position I would try to swing).

Sakana emerged in 2023 out of Tokyo, founded by David Ha and Llion Jones — one of the co-authors on “Attention Is All You Need”. From the start, they positioned themselves as a research lab with a thesis: nature-inspired AI, evolutionary approaches, directions the big labs weren’t prioritizing.

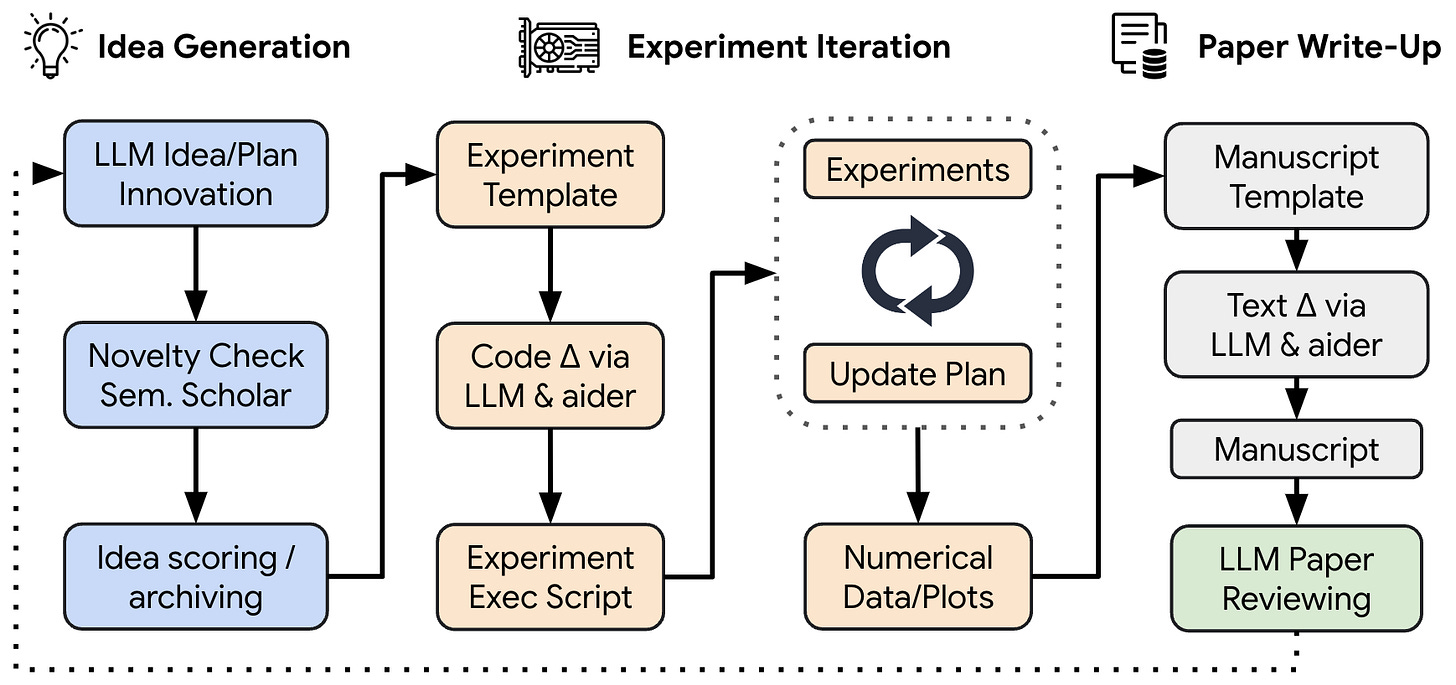

Consequently, what they shipped wasn’t enterprise software. It was ideas — packaged as papers, code, and working systems. Elaborate PoCs to prove a point.

The AI Scientist project proposed something genuinely weird: a system that could autonomously generate research hypotheses, write code to test them, run the experiments, and write up the results.

Their evolutionary model merging work was similarly directional. Instead of training models from scratch with massive compute, you could “breed” existing models together — recombining their weights in ways inspired by biological evolution to create better performance without billion-dollar training runs.

None of this was designed for production deployment. It was designed to be interesting — to the specific people who decide where frontier AI goes next.

Google didn’t invest in Sakana because they needed another model. They invested because Sakana represented epistemic insurance — a credible bet on a non-Transformer future. By partnering early, Google bought an option on a research direction that might become important, secured access to a team that had proven publicly they could think orthogonally to the mainstream, and locked in distribution through Google Cloud before anyone else could.

The open research phase made this possible by collapsing diligence. If Sakana had been closed — just a slide deck promising “evolutionary AI” — Google’s evaluation would have taken months. They’d have to verify everything from scratch. Because the work was public, the diligence was effectively done by the community. The citations, the reproductions, the technical discussions on Twitter — that was the diligence. By the time Google showed up, the answer was already “yes.”

This is authority capture: use openness to make your judgment legible, attract the attention of players who think long-term, and convert that attention into capital, partnerships, and distribution that would otherwise take years to earn.

But there’s an uncomfortable truth here. This path is harder to copy than infrastructure capture.

SGLang’s playbook is replicable — build something useful, let it spread, monetize the dependency. Sakana’s playbook requires something less fungible: genuine research taste and the pedigree to back it up + an insane amount of luck to be spotted by the right people. Having the Transformer author was a huge boost here; most startups trying to pull this off will not be able to rely on this as a signal boost.

But when this open research play works, it can have an insane return on time. Building something that has mass adoption requires hammering a lot of time into edge cases and other boring engineering work. Sakana’s style is trying to hit home-runs constantly. All they need is one to drive attention to themselves, and the rest plays off very well.

How do you know what path to pick for yourself? Let’s discuss that next.

Two Paths, Two Kinds of Leverage

Infrastructure capture reduces execution risk. Authority formation reduces epistemic risk. That’s the whole distinction.

SGLang’s evaluators were engineers asking “will this work under our constraints?” Proof was usage. Leverage was switching costs — once you’re in the critical path, removal is painful.

Sakana’s evaluators were research leaders and hyperscaler strategy teams asking “does this team see something others don’t?” Proof was coherence over time. Leverage was optionality — Google bought exposure to a possible future, not software they needed today.

The failure modes are inverses. Infrastructure capture fails when adoption doesn’t create dependency — GitHub stars but no pricing power, useful but replaceable. Authority formation fails when credibility doesn’t create trust — Twitter followers but no leverage, interesting but directionless.

The common mistake is mixing signals. Teams open-source a half-baked system hoping for adoption and respect and capital. They get stuck in the middle: too vague to be infrastructure, too shallow to signal authority. Even projects that have the potential to be both are better served by focusing on the two paths. For example, when we open-sourced our latent space reasoning infrastructure for Iqidis, we focused on Sakana style street cred over SGlang style adoption (becoming a reasoning infrastructure for general purpose tasks would spread us too think at this stage). Our idea for reasoning in the latent space was very out there, so the code was meant to prove that we could actually back up our talk, nothing more. Thus, our Github was oriented towards proving the idea beyond doubt, as opposed to taking care of deployment-oriented tasks (you can see it here).

Openness becomes a killer since it exposes the confusion faster.

For capital, the evaluation is different too. Infrastructure plays look like traditional software investing with delayed monetization — you’re underwriting adoption curves and eventual enterprise conversion. Authority plays look like research bets — you’re underwriting taste and timing, whether this team is working on something that matters before it’s obvious. They should both be evaluated differently and priced accordingly.

Conclusion: What This Means for Builders

Open doesn’t make you interesting. It reveals whether you were interesting to begin with.

If you’re early — pre-product, pre-revenue, pre-market — the question isn’t “should we be open?” It’s “what would the smartest person in the room find if they pulled apart our work right now?”

If the answer is nothing, then Open Sourcing will only open your mediocrity to the world. Focus on UX, GTM, and other aspects to give your project a leg up in the world.

If the answer is something, open is the fastest way to let the right people find it before everyone else catches up — a zipline to some of the top people in the industry. Opening my research was one of the best decisions I ever made because it got me all kinds of introductions that I could not get otherwise (including C-Suite at Big Tech and prominent AI Researchers). Imo the tradeoff is almost always worth taking.

The filter for serious attention is open. Whether your work survives it is the only question that matters.

Thank you for being here, and I hope you have a wonderful day,

Dev <3

If you liked this article and wish to share it, please refer to the following guidelines.

That is it for this piece. I appreciate your time. As always, if you’re interested in working with me or checking out my other work, my links will be at the end of this email/post. And if you found value in this write-up, I would appreciate you sharing it with more people. It is word-of-mouth referrals like yours that help me grow. The best way to share testimonials is to share articles and tag me in your post so I can see/share it.

Reach out to me

Use the links below to check out my other content, learn more about tutoring, reach out to me about projects, or just to say hi.

Small Snippets about Tech, AI and Machine Learning over here

AI Newsletter- https://artificialintelligencemadesimple.substack.com/

My grandma’s favorite Tech Newsletter- https://codinginterviewsmadesimple.substack.com/

My (imaginary) sister’s favorite MLOps Podcast-

Check out my other articles on Medium. :

https://machine-learning-made-simple.medium.com/

My YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/@ChocolateMilkCultLeader/

Reach out to me on LinkedIn. Let’s connect: https://www.linkedin.com/in/devansh-devansh-516004168/

My Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/iseethings404/

My Twitter: https://twitter.com/Machine01776819

Thanks for writing this, it clarifies a lot about the current landscape. But what if the drive for such massive valuations eventually makes the 'open' part of open source AI just a stepping stone for proprietery systems?

Read my articles.