Why You Should Read: Don Quixote [Recs]

Why a 500 year old novel about a madman is one of the most relevant stories today

It takes time to create work that’s clear, independent, and genuinely useful. If you’ve found value in this newsletter, consider becoming a paid subscriber. It helps me dive deeper into research, reach more people, stay free from ads/hidden agendas, and supports my crippling chocolate milk addiction. We run on a “pay what you can” model—so if you believe in the mission, there’s likely a plan that fits (over here).

Every subscription helps me stay independent, avoid clickbait, and focus on depth over noise, and I deeply appreciate everyone who chooses to support our cult.

PS – Supporting this work doesn’t have to come out of your pocket. If you read this as part of your professional development, you can use this email template to request reimbursement for your subscription.

Every month, the Chocolate Milk Cult reaches over a million Builders, Investors, Policy Makers, Leaders, and more. If you’d like to meet other members of our community, please fill out this contact form here (I will never sell your data nor will I make intros w/o your explicit permission)- https://forms.gle/Pi1pGLuS1FmzXoLr6

“In short, he became so absorbed in his books that he spent his nights from sunset to sunrise, and his days from dawn to dark, poring over them; and what with little sleep and much reading his brains got so dry that he lost his wits.”

Don Quixote is a story of a deeply moral man who dreams with everything he has — who gives himself over to absurd, unwinnable, outdated ideals — and fails completely. He suffers for his ambition (often physically), works harder than most characters ever will, and tries to help all around him. In other words, he does everything a protag-kun does. And yet, he does not slay dragons. He does not win the girl. He dies alone, having lost his mind and his dignity.

Don Quixote is also one of the most life-affirming stories I’ve ever read. Not despite this outcome, but because of it. While most stories around following your dreams and having grand visions are about succeeding against all odds, Don Quixote shows us the story of a man whose pursuit breaks him. DQ is life-affirming because Cervantes shows us that a life spent in a noble pursuit can be valuable, can uplift people, can make a mark even if we completely fail to accomplish our goals.

That’s what makes Don Quixote worth reading. Not as a comedy. Not as a tragedy. But a book that seriously grapples with the question — is a failed life worth living — and gives us a clear yes.

And I’d say that in an industry flooded by imitation products, attention whoring, and a deep fear of taking big risks due to the worry about failure, Don Quixote stands as an enduring reminder that sometimes failing doesn’t invalidate the pursuit of a larger ambition.

Don Quixote is mandatory reading for a world so scared of failing that they build templates and frameworks for spotting disruption. Mandatory reading for an industry that’s so timid about the future that they need to pinch pennies and try to suck value out of every cranny b/c they’re scared to get out of their comfort zones.

Executive Highlights (TL;DR of the Article)

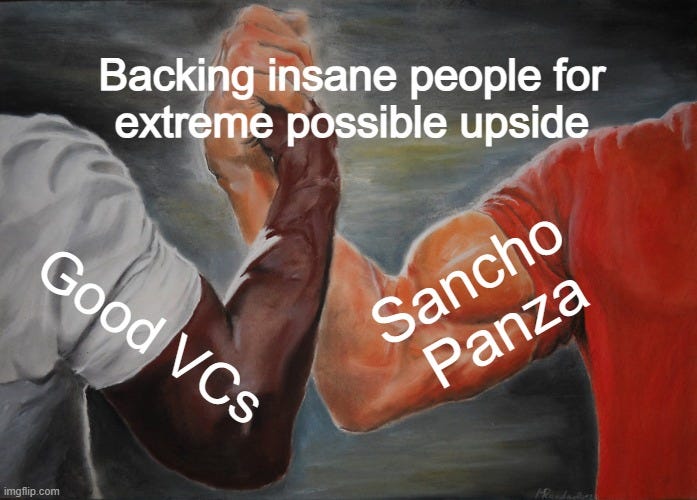

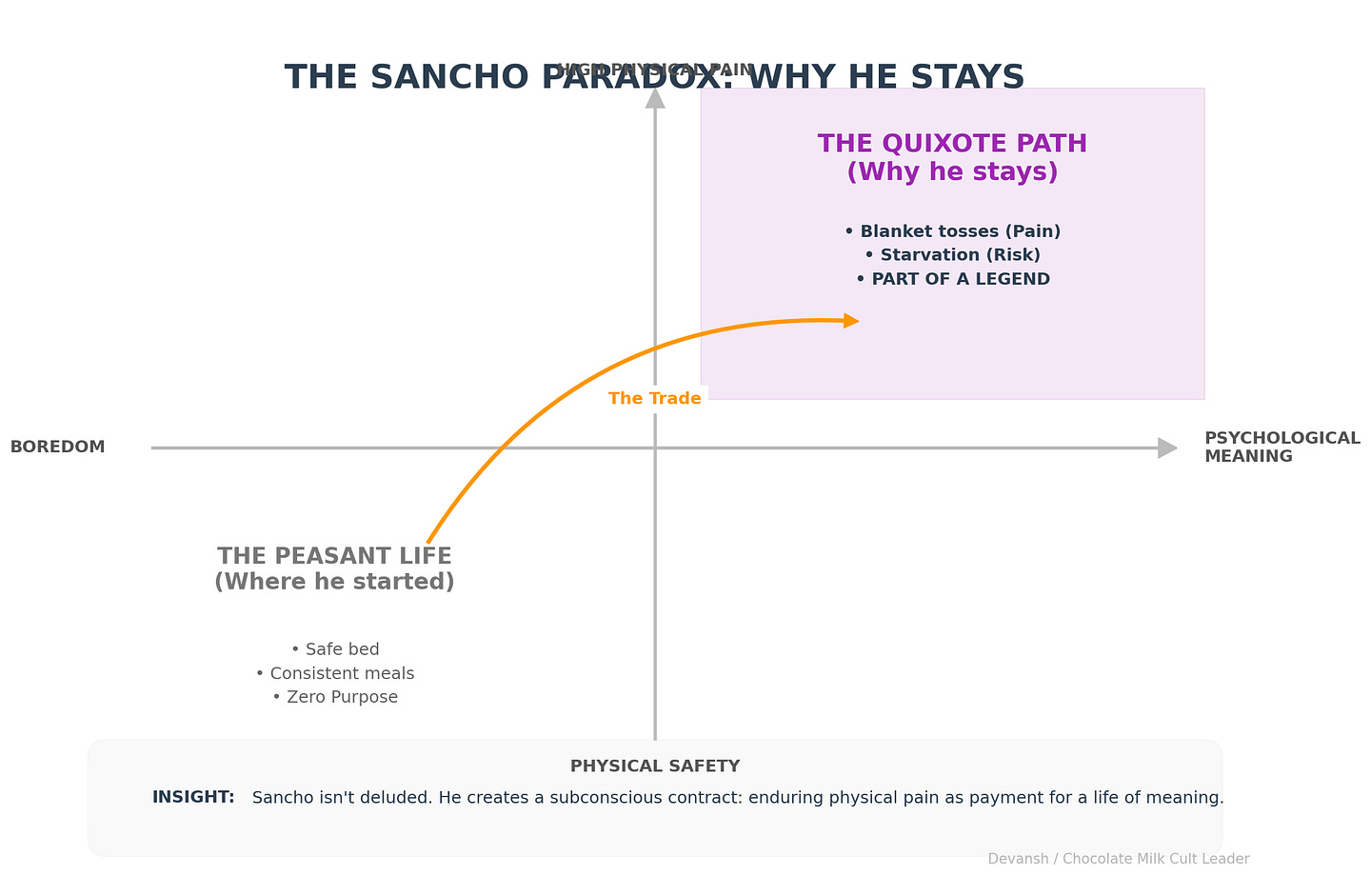

The unlock to the book isn’t Don Quixote. It’s Sancho Panza. A sane, pragmatic peasant who sees the windmills, knows his master is mad, suffers for it constantly — and stays anyway. The question that cracks the book open: why does the rational person follow the lunatic?

Sancho isn’t deluded. He’s making a trade: physical safety and boredom for pain and meaning. Proximity to someone who refuses to accept the world as given is worth getting tossed in a blanket.

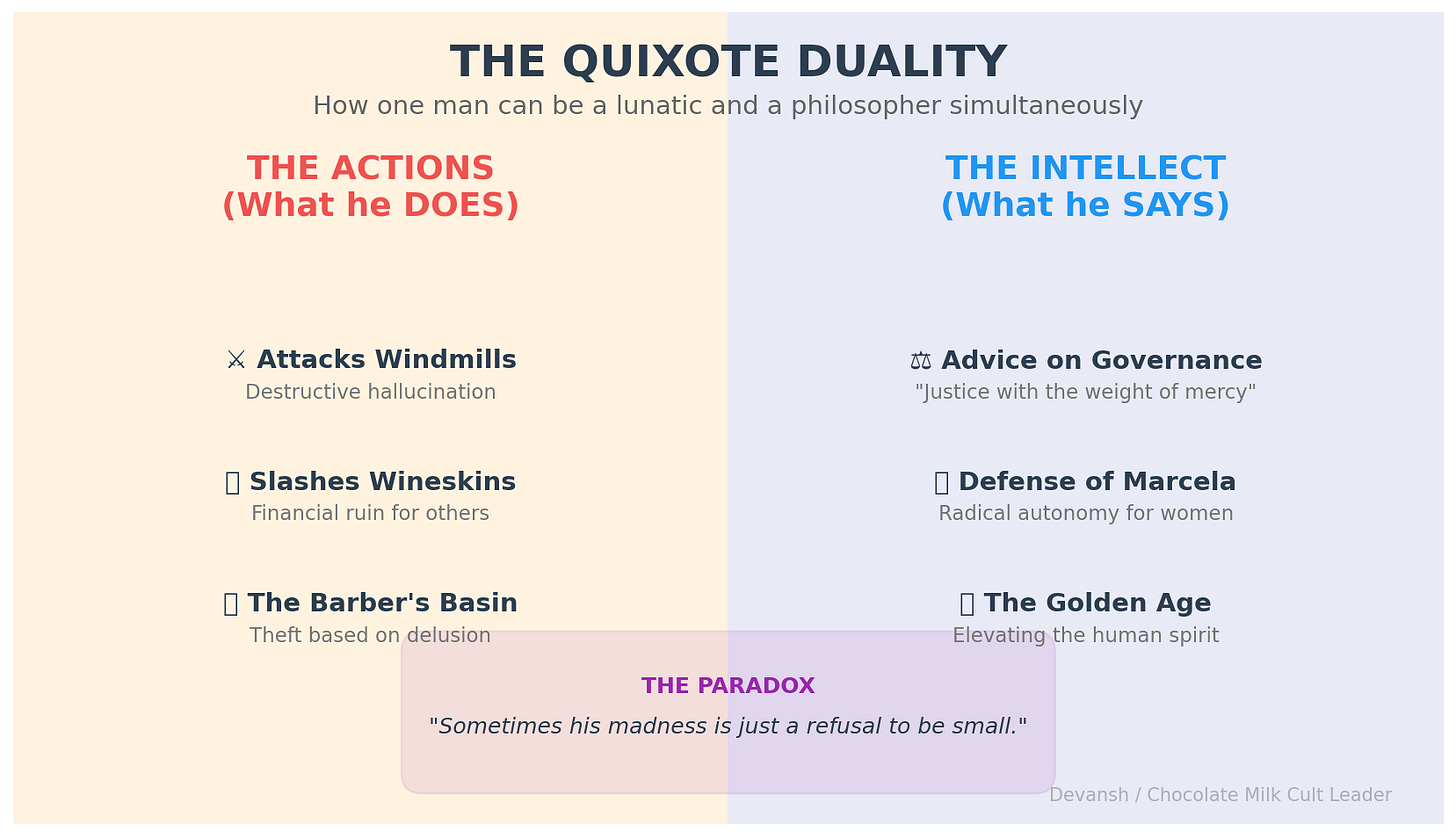

DQ’s “madness” is sometimes just a refusal to be small. He defends a woman’s right to reject suitors in 1605. He speaks to peasants about justice and mercy as if they’ll one day govern. Between the disasters, he’s running a rolling seminar on how to live.

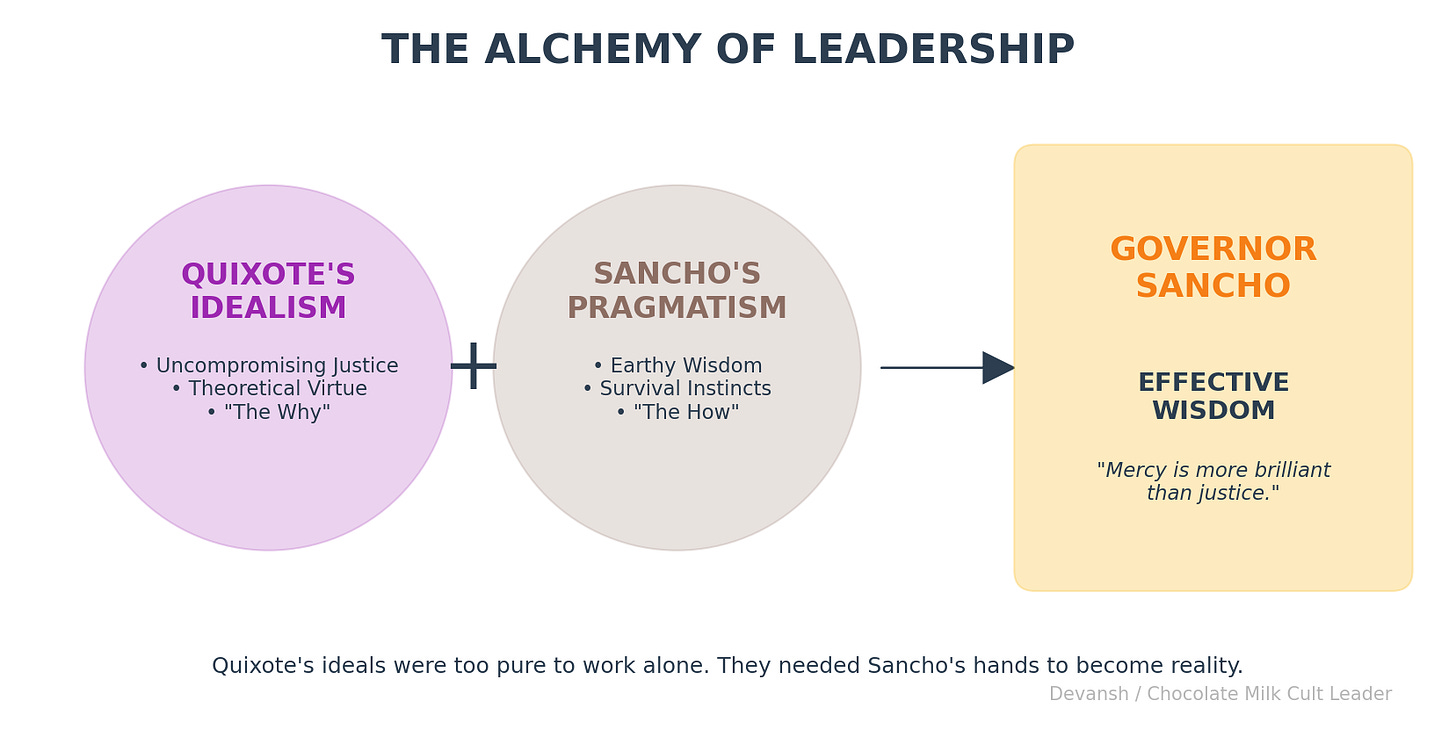

The payoff: Sancho becomes governor, faces an impossible paradox, and rules with wisdom he didn’t learn from books — he learned it from months of listening to a madman talk about honor. Quixote’s idealism, too pure to function alone, got filtered through Sancho’s pragmatism and became effective.

By the end, DQ wants to die sane. Sancho begs him to stay mad. The torch passes. The dream outlives the dreamer and elevates people through it’s presence. This is the true legacy of Don Quixote, the mad knight.

PS- If you’re more of an audio person, highly recommend this lecture by Michael Sugrue on Don Quixote.

I put a lot of work into writing this newsletter. To do so, I rely on you for support. If a few more people choose to become paid subscribers, the Chocolate Milk Cult can continue to provide high-quality and accessible education and opportunities to anyone who needs it. If you think this mission is worth contributing to, please consider a premium subscription. You can do so for less than the cost of a Netflix Subscription (pay what you want here).

I provide various consulting and advisory services. If you‘d like to explore how we can work together, reach out to me through any of my socials over here or reply to this email.

The Man Who Fought Wineskins

“‘Look there, friend Sancho Panza, where thirty or more monstrous giants present themselves, all of whom I intend to do battle with and deprive of all their lives…’

‘What giants?’ said Sancho Panza.

‘Those you see there,’ answered his master, ‘with the long arms, and some have them nearly two leagues long.’

‘Look, your worship,’ said Sancho; ‘what we see there are not giants but windmills…’ ”

This is the scene that defines him. On a broad plain, under the Spanish sun, Don Quixote sees an army of giants. His squire, Sancho Panza, sees windmills. Quixote, convinced of his righteousness, charges. A gust of wind spins the sails, his lance is smashed to pieces, and both knight and horse are sent rolling across the field in a painful, pathetic heap.

This is the pattern of the book, repeated endlessly.

He mistakes a flock of sheep for two dueling armies, charges in, and is knocked senseless by the shepherds’ slingshots. He mistakes large wineskins for a giant, hacks them to pieces with his sword, and floods an entire inn with red wine, for which he must then pay. He mistakes a barber’s basin for the mythical golden Helmet of Mambrino. He addresses two prostitutes at an inn as if they were high-born princesses.

The analysis, for most, begins and ends here. It is the story of a man whose brain has been broken by books. He cannot distinguish reality from fiction, and he suffers for it. He is a comic figure, a tragic one, or a bit of both. It is a sad, funny tale about the dangers of delusion.

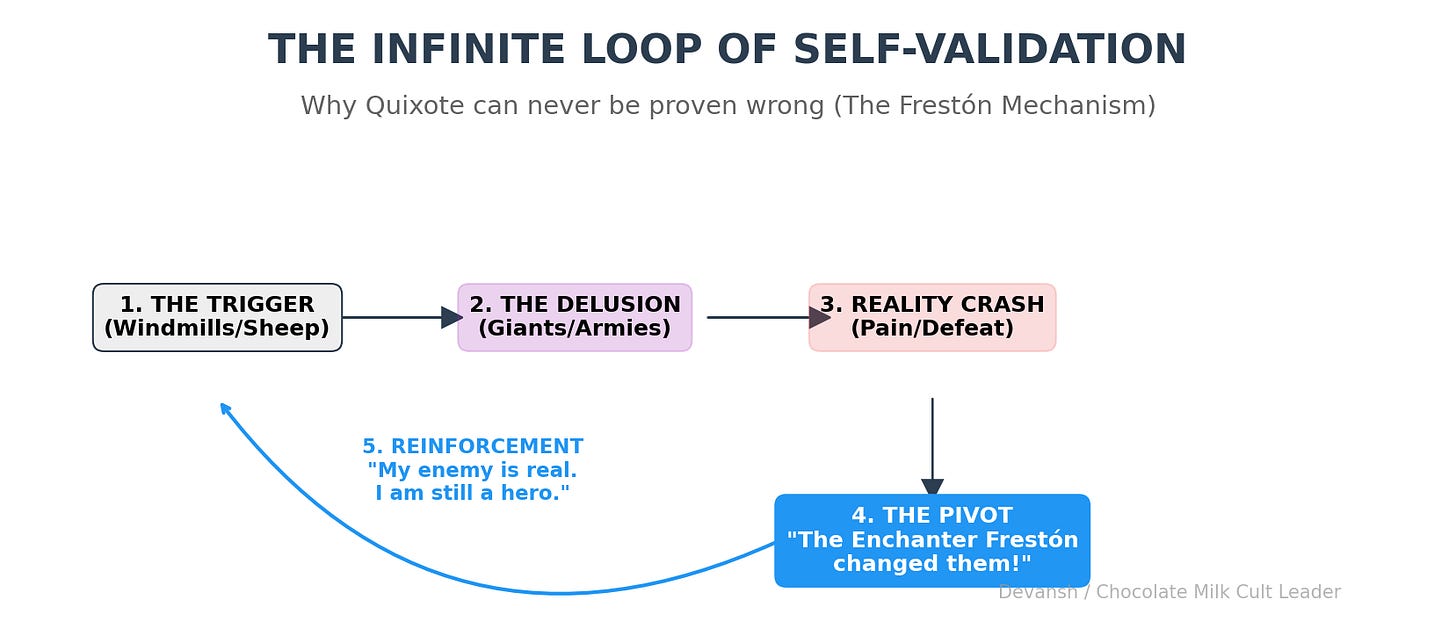

“This is the work of my enemy, the magician Frestón, who stole my books. He has changed these giants into windmills to cheat me of the glory of vanquishing them.”

And this is where the story should get boring. A madman is only interesting for so long. His predictable failures, his unfalsifiable excuse that an evil enchanter is always one step ahead of him — this is a thin premise for a 900-page book. Even with all the side-quests, the fundamental premise of the book gets really old really quickly.

So why has Don Quixote endured for so long? The secret lies in the Shinpachi to Don Quixote’s Gintoki. The second, often overlooked, man on the field.

Sancho Panza.

Sancho is not mad. He sees the windmills. He smells the sheep. He tastes the wine. He is described as a simple peasant, but he is no fool. He is pragmatic, cautious, and deeply invested in reality. He is also the one who suffers the consequences of Quixote’s madness most directly. When Quixote refuses to pay an innkeeper, it is Sancho who is grabbed by a group of men, tossed in a blanket, and hurled into the air until he is bruised and breathless. He goes hungry. He gets beaten. He loses his possessions.

And yet, he stays.

This is the question that unlocks the entire book. Why does this sane, practical man, who gains nothing but pain and hardship, continue to follow this madman? What does Sancho see in the knight’s ridiculous, failed charges that we, the sensible readers, are missing?

The simplistic explanation is that Sancho is hoping for the day that Don Quixote gives him a kingdom. That Sancho is misled by DQ’s delusions. But think about how quickly Sancho understands that DQ is a few crayons short. That DQ is not what he says he is. Clearly, Sancho is not blind.

So what keeps him around? It’s much simpler than you might think.

The Refusal to Accept the World as Given

“Consider, Sancho, if by chance you should come to be a governor, as we have had some hope you may, be sure not to turn aside from the path of justice, which is the principal virtue in a ruler. If you must bend it, let it be with the weight of mercy, not the weight of bribes.”

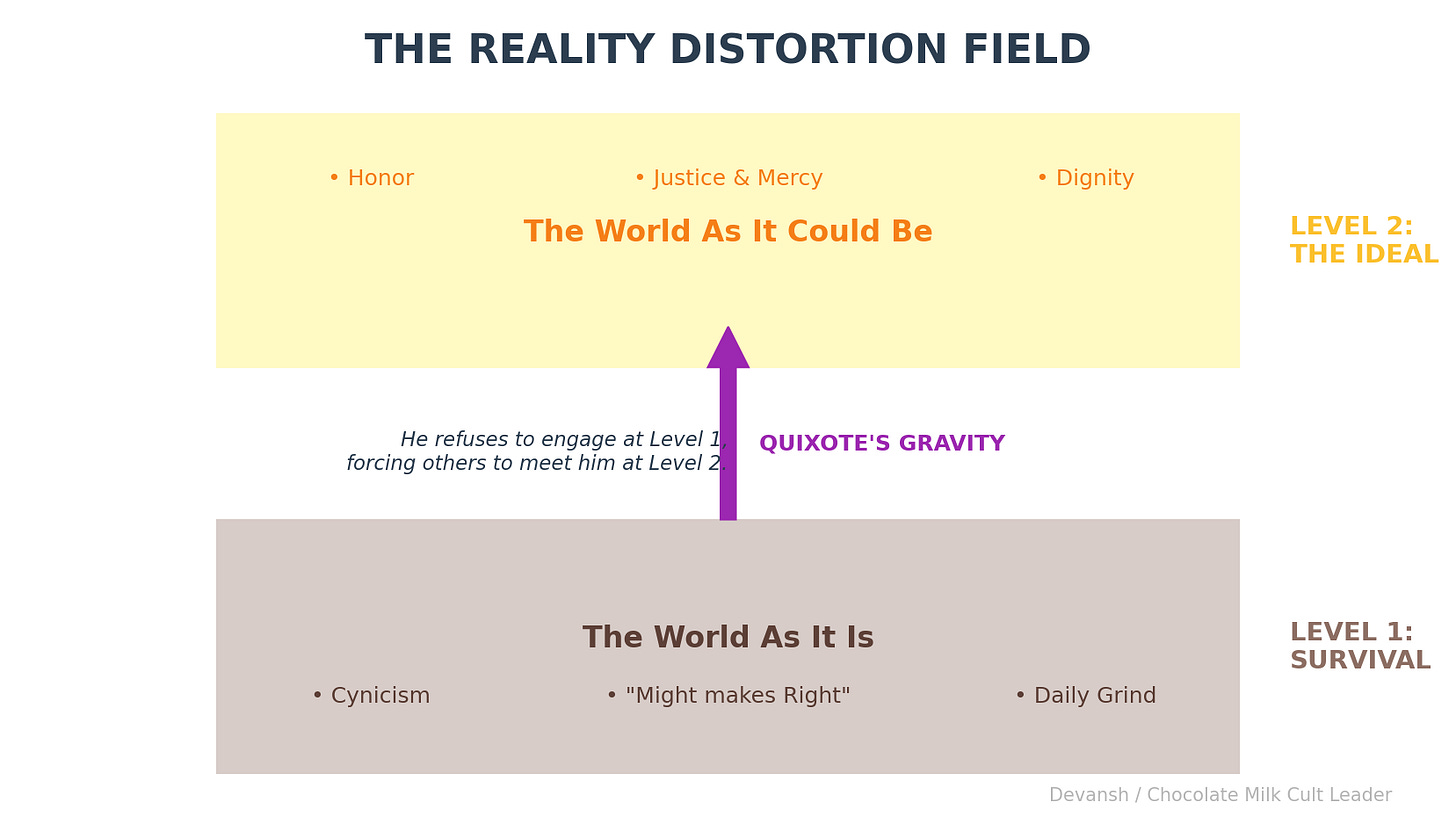

This is someone who has spent years contemplating the responsibilities that come with power. About the weight of law. About the dignity of the poor. And he’s saying this not to a king, not to a knight or another high-born person who he could impress with his moral goodness, but to a peasant. The advice is not performative. It’s intimate. Thoughtful. Earnest.

That’s Don Quixote at his peak.

Yes, he attacks windmills. Yes, he floods inns by slashing wineskins. Yes, he confuses prostitutes for princesses and barbers’ bowls for golden helmets. But between these disasters, he also speaks clearly, and often beautifully, about what a good life looks like. About virtue. About kindness. About honor.

Sometimes his madness isn’t madness at all. Sometimes it’s just a refusal to be small. No moment shows this more clearly than the defense of Marcela.

A young shepherd, Grisóstomo, falls in love with her and is rejected. He dies from heartbreak. At his funeral, the other men blame Marcela for his death. They say she was cold, cruel, that she led him on. That it’s unnatural for a beautiful woman to reject love when it’s offered. The village and other shepherds immediately blame Marcela for his death. They call her cruel, heartless, a murderess. The logic is familiar. So is the budding violence beneath it.

Most people, Sancho included, would nod along. The crowd blames the woman; therefore, she must be guilty. It’s simpler that way. It fits the narrative of tragic love.

And then Marcela speaks.

“You say that because I am beautiful, I must therefore love. I say that because I do not love, I must not be blamed. Love must arise freely, not from obligation. I have never given hope to Grisóstomo. I have never promised affection. I warned him. And now, because he chose to hope against my word, I am called cruel?”

“Let it be known: I was born free, and I live free, and I will die free. I do not wish to bind myself to anyone. And I owe no one an explanation.”

This is in a novel written in 1605.

Don Quixote doesn’t waver. He hears her speech and then turns to the crowd of angry men and tells them flatly that she is right. He puts himself in the middle, willing to fight for a stranger’s freedom, just because he sees it as the right thing.

“She was born free, and to live free she chose the solitude of the fields. The trees on these mountains are her company, the clear waters of these streams her mirrors; to the trees and the waters she communicates her thoughts and reveals her beauty. She is a fire set apart, a sword laid aside. She slays and destroys no one but the person she is destined for… Let no one, therefore, of whatever state or condition he may be, dare to follow the beautiful Marcela, on pain of falling into my furious indignation. She has shown by clear and sufficient reasons that the fault was not hers, and how far she is from yielding to the desires of any of her lovers; for which reason, instead of being followed and persecuted, she deserves to be honored and esteemed by all good people in the world…”

This happens a lot. Whether or not DQ understands the situation correctly, it’s clear that he’s always willing to put himself in the firing line for his ideals.

He meets goatherds and speaks to them of the Golden Age. Has incredibly wise debates that impressed the most learned characters. He constantly elevates the conversation, dragging the people around him up from the mud of their daily survival into a world of legends and ideas and ethics.

He is contagious.

The “madness” of Don Quixote is that he acts as if the world is a place where honor, justice, and dignity are the most important things. And because he commits to the bit so hard, the world around him is forced to warp slightly to accommodate him.

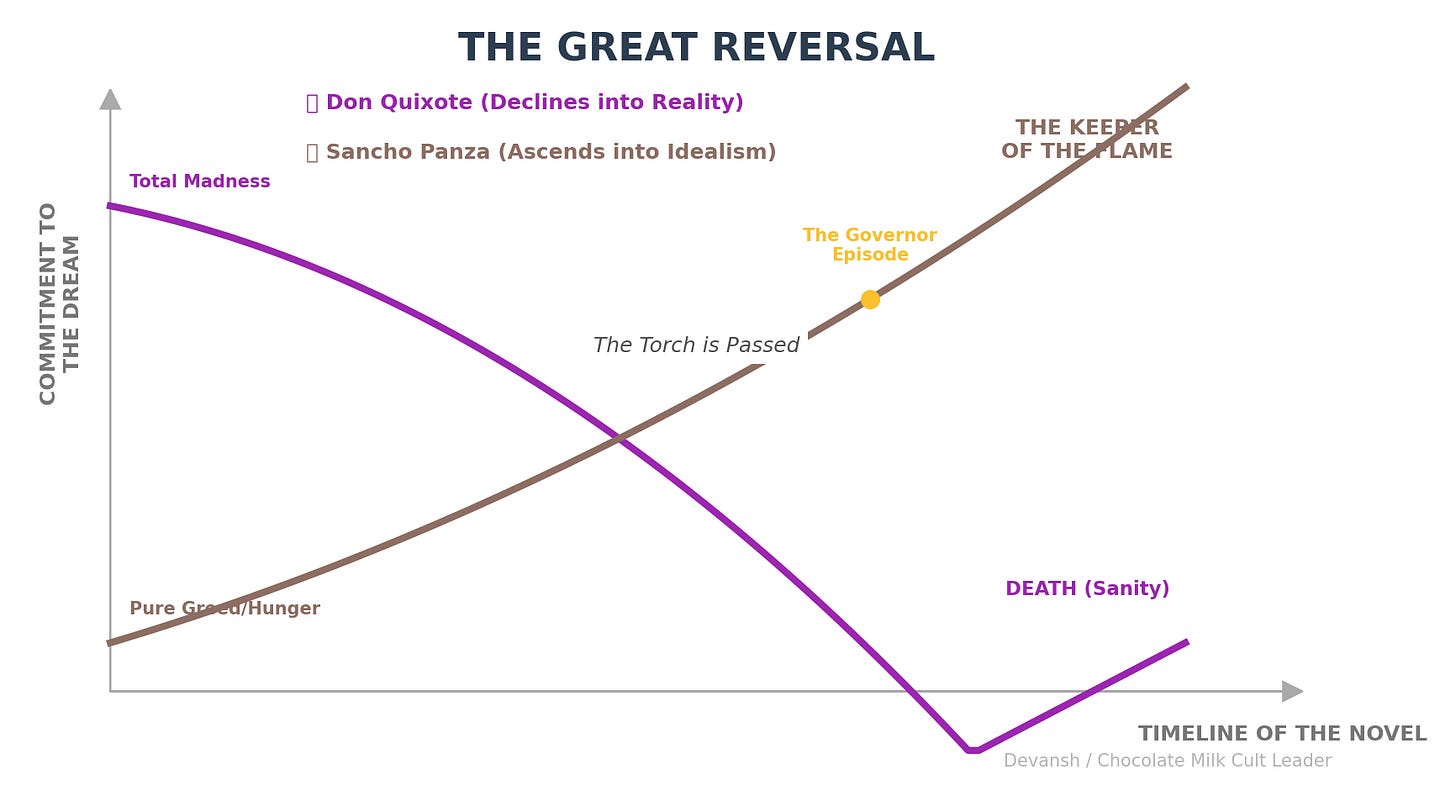

This change is embodied best through Sancho, the squire who suffers despite his rationality. Being around Don Quixote for so long catalyzes an Endeavor-level (my fav redemption arc OAT) character arc for Sancho.

Don Quixote begins the novel as a man transformed by books. Sancho ends it as a man transformed by Don Quixote. And that is one of the biggest reasons to read Don Quixote.

The Peasant Who Became a King

“All I know is that while I’m asleep, I’m not troubled by hopes or fears, by troubles or glories. Praise be to the man who invented sleep, a cloak that covers all a man’s thoughts, the food that slakes all hunger, the water that quenches all thirst, the fire that warms the cold, the cold that cools the heat; in short, the coin that can buy anything, the scales and weights that make the shepherd equal to the king and the simple man to the sage.”

This is Sancho Panza’s philosophy at the start of the book. It is the earthy wisdom of a man who has known nothing but survival. His concerns are food, sleep, and money. He is a good man, but a simple one. He follows Don Quixote not out of idealism, but in the pragmatic hope that he will be rewarded with an island to govern.

And then, late in the book, a Duke and Duchess decide to make that dream a reality as a practical joke. They install Sancho as the governor of a small town, sending a stream of actors with complex legal disputes his way, expecting him to make a fool of himself for their amusement.

They expect an illiterate peasant. They do not expect the man who has spent months in a rolling seminar on justice with Don Quixote.

The ultimate test comes in the form of a paradox. A bridge in his domain has a law: anyone who crosses must state their destination truthfully on pain of death by hanging. One day, a man arrives and declares, “I have come here to die on that gallows, and for no other reason.”

The judges are paralyzed. If they hang him, he told the truth, and so he should have been allowed to pass freely. If they let him pass, he lied, and so he should be hanged. It is a perfect, unbreakable loop. Justice is stumped.

Sancho, the simple peasant, considers the problem. And this is his ruling:

“In this case, I say that you should let the man pass freely, for it is always more praiseworthy to do good than to do evil. And this I would give you signed with my name if I knew how to write. And in this I am not speaking from my own head, but rather there has come to my mind a precept, among the many that my master Don Quixote gave me… that when justice was in doubt, I should lean and incline to the side of mercy.”

He doesn’t do this because he read philosophy.

He does this because he was infected with the spirit of Don Quixote.The idealism of Don Quixote, which was too pure and uncalibrated to function in the world, was filtered through Sancho’s pragmatism. What emerged was not madness, but effective wisdom. The peasant who only wanted to eat and sleep had become a king who understood that mercy is more brilliant than justice.

And when he finally steps down from power, he doesn’t blame Don Quixote. He doesn’t renounce the journey. He returns to his master — not out of delusion, not out of obligation — but because something in him still believes.

By the end of the novel, Sancho is the one trying to keep the dream alive. He’s the one begging Don Quixote not to abandon his madness. Not to become sane. Not to die, not to give up on his adventures.

He’s lived on all sides of the spectrum, and Sancho is choosing to embrace the loony way of life.

The Death of Don Quixote

“Forgive me, my friend, for the opportunity I gave you to seem as mad as I, making you fall into the same error I did, of believing that there were and are knights-errant in the world.”

On his deathbed, Don Quixote wakes up.

The fever breaks, and with it, the enchantment. He is no longer Don Quixote of La Mancha, the knight-errant. He is Alonso Quijano, a country gentleman. He sees with perfect clarity that there are no giants, no enchanters, no damsels in distress.

And he is horrified. He apologizes to Sancho for the madness, for the lies, for the wasted time. He renounces his entire quest.

This should be the triumphant moment. The hero is cured. Sanity is restored. This is what the characters have been praying for since the beginning.

And yet, Sancho, the one who has suffered the most, says this —

“Oh, your worship,” replied Sancho, weeping, “do not die; but take my advice and live for many years; for the greatest madness a man can commit in this life is to let himself die, just like that, without anybody killing him, or any other hands finishing him off except those of melancholy… Look, don’t be lazy, but get up from that bed, and let’s go out into the countryside dressed as shepherds… Perhaps behind some bush we shall find the lady Dulcinea, disenchanted, as fine as you could wish.”

Don Quixote, the man who gave his whole life to an ideal, dies renouncing it.

Sancho, the man who began with no ideals, is left to carry its spirit.

The pursuit did not give Don Quixote what he wanted. It did not make him a hero or win him a princess or restore the Golden Age. But it transformed a simple peasant into a man noble enough to understand that a world without giants is not a safer world. It is a smaller one.

Conclusion: Don Quixote can never die

The book ends with the death of Alonso Quijano. And yet, Don Quixote lives on, through the canonical stories told about him. Through the various people who remember their discussions with him.

And most importantly, through Sancho Panza, who becomes a true spiritual heir to DQ when he tells DQ to deny death so that he and Sancho can adventure together again.

And that’s why Don Quixote can never die. It is immortal. It is the immortal spirit of heroism, of idealism, of imagination, forcing the world to accommodate it rather than accommodating our minds to the world around us. It elevates us, undercutting nihilism and defeatism by reminding us although many of our aspirations may crumble, there is still a sort of spiritual grandeur attached to them nonetheless. Despite all our failings, our strivings ennoble us.

That’s what makes Don Quixote so life-affirming, so worth reading: because it looks at the brutal cost of living by a mission, shows you what happens when you fail, and still provides a clear answer to why it’s worth it. Independent of everything else.

And very few stories can claim to do that.

Thank you for being here, and I hope you have a wonderful day,

Dev <3

If you liked this article and wish to share it, please refer to the following guidelines.

That is it for this piece. I appreciate your time. As always, if you’re interested in working with me or checking out my other work, my links will be at the end of this email/post. And if you found value in this write-up, I would appreciate you sharing it with more people. It is word-of-mouth referrals like yours that help me grow. The best way to share testimonials is to share articles and tag me in your post so I can see/share it.

Reach out to me

Use the links below to check out my other content, learn more about tutoring, reach out to me about projects, or just to say hi.

Small Snippets about Tech, AI and Machine Learning over here

AI Newsletter- https://artificialintelligencemadesimple.substack.com/

My grandma’s favorite Tech Newsletter- https://codinginterviewsmadesimple.substack.com/

My (imaginary) sister’s favorite MLOps Podcast-

Check out my other articles on Medium. :

https://machine-learning-made-simple.medium.com/

My YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/@ChocolateMilkCultLeader/

Reach out to me on LinkedIn. Let’s connect: https://www.linkedin.com/in/devansh-devansh-516004168/

My Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/iseethings404/

My Twitter: https://twitter.com/Machine01776819

You’re a wonderful writer!

Wonderful piece. Thank you