It takes time to create work that’s clear, independent, and genuinely useful. If you’ve found value in this newsletter, consider becoming a paid subscriber. It helps me dive deeper into research, reach more people, stay free from ads/hidden agendas, and supports my crippling chocolate milk addiction. We run on a “pay what you can” model—so if you believe in the mission, there’s likely a plan that fits (over here).

Every subscription helps me stay independent, avoid clickbait, and focus on depth over noise, and I deeply appreciate everyone who chooses to support our cult.

PS – Supporting this work doesn’t have to come out of your pocket. If you read this as part of your professional development, you can use this email template to request reimbursement for your subscription.

Every month, the Chocolate Milk Cult reaches over a million Builders, Investors, Policy Makers, Leaders, and more. If you’d like to meet other members of our community, please fill out this contact form here (I will never sell your data nor will I make intros w/o your explicit permission)- https://forms.gle/Pi1pGLuS1FmzXoLr6

Ye Wang is the Founder and CEO of EverCurrent—an entrepreneur, researcher, and engineer. Raised by industrial designer and manufacturing parents, she’s spent her career building software for hardware teams, with experience at Autodesk, Onshape, and Join. She was one of my favorite founders in this cohort of a16z Speedrun, and we had a lot of fun talking about EverCurrent and the current problems hitting hardware development.

EverCurrent tackles one of the hardest underlying problems in hardware: deep domain knowledge, cross-functional dependencies, and high-stakes change decisions that directly impact speed and quality. Using AI, EverCurrent helps teams manage change and knowledge, unlock hidden capacity, and proactively close gaps in execution.

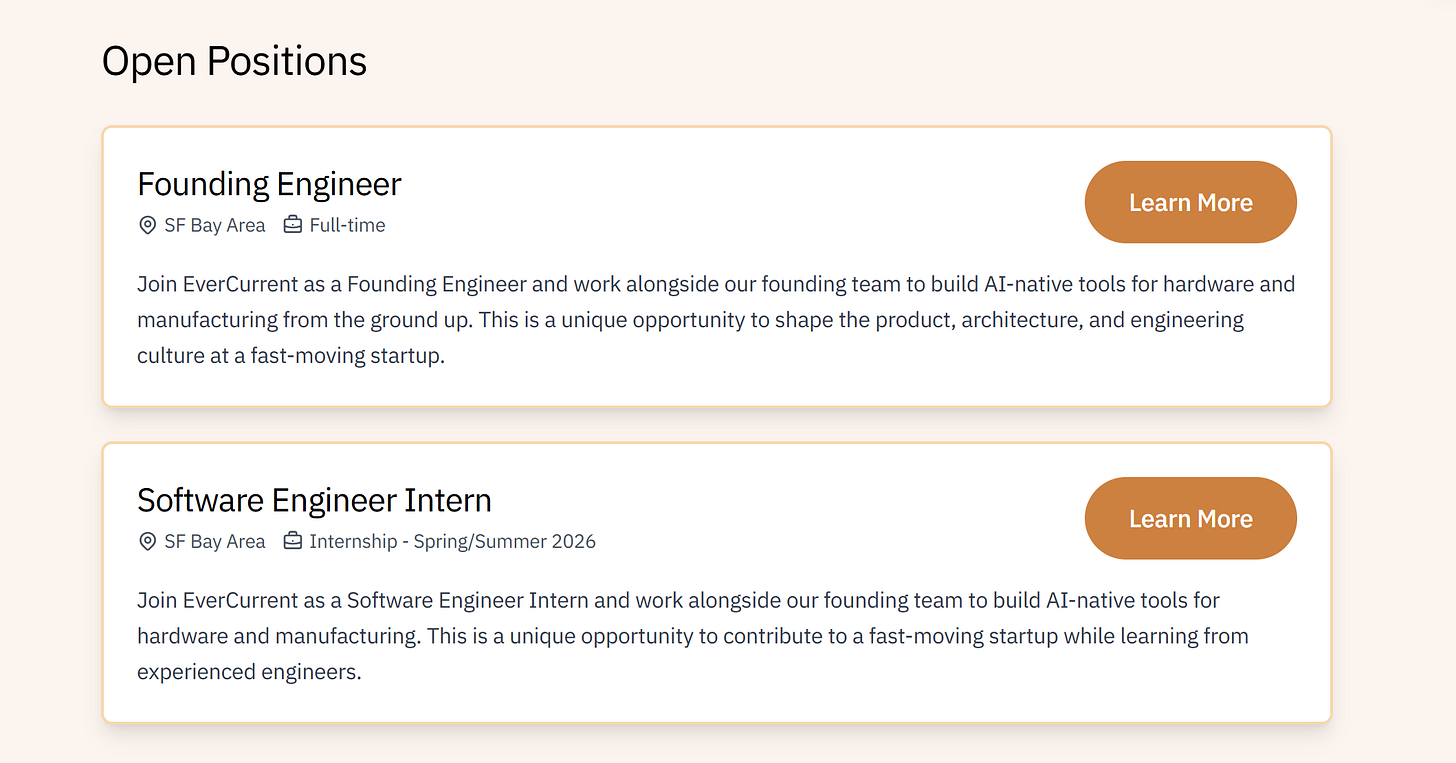

If you know visionary hardware founders or teams tired of manually stitching context behind decisions and knowledge, send Ye a message. And if you’re a talented engineer looking to make meaningful impact, learn more at evercurrent.ai/careers.

Before we get into it, we have a new foster cat that’s ready to be adopted. I call him Chipku (Hindi for clingy; his government name is Jancy), and as you might guess, he’s very affectionate. I’ve trained him to be better around animals and strangers, and he’s perfect for families that already have some experience with cats. We sleep together every day, and waking up to him is one of the nicest feelings. If you’re around New York City, adopt him here (or share this listing with someone who might be interested).

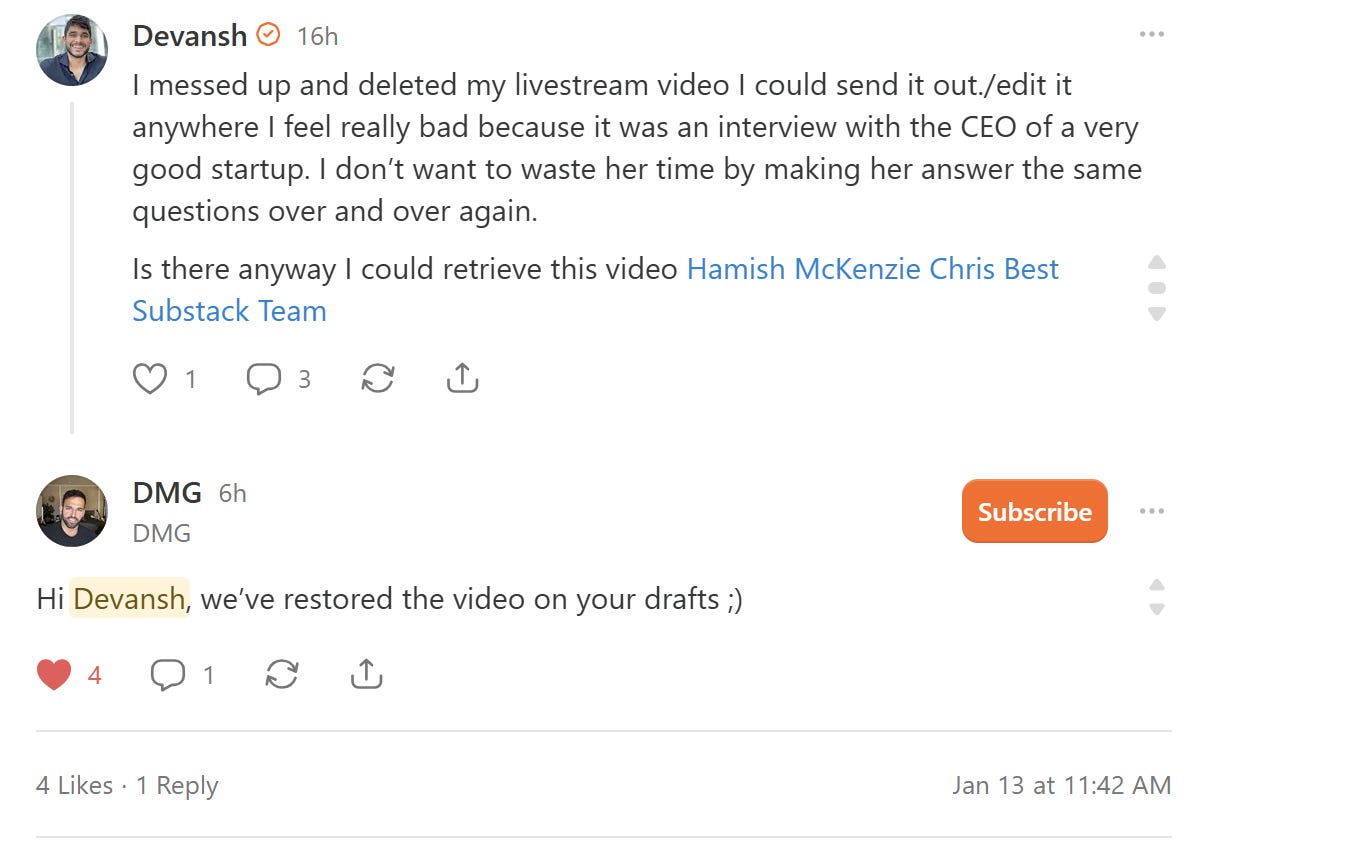

Also, my dumbass deleted the video recording with no backups by accident (that’s why we didn’t publish yesterday). Shoutout to the Substack team for their really prompt assistance on the matter. So give Chris Best , DMG , Hamish McKenzie, and the rest of the Substack team your best virtual smooches for their clutch assist.

Companion Guide to the Livestream: Ye Wang on Hardware’s Knowledge Problem

This guide expands the core ideas and structures them for deeper reflection. Watch the full stream for tone, nuance, and side-commentary.

1. Why Hardware Teams Haven’t Experienced AI Productivity Gains

The core problem isn’t tooling—it’s knowledge architecture. Software teams have their knowledge consolidated in ways AI can leverage. The codebase is the source of truth. Issues trace to commits. Dependencies are explicit in package managers and import statements. A new engineer can git blame their way to understanding why something exists.

Hardware teams operate in a fundamentally different reality. Mechanical engineers use MCAD (SolidWorks, Creo, Fusion). Electrical engineers use ECAD (Altium, KiCad, Cadence). Supply chain runs on spreadsheets and legacy ERP systems. Firmware lives in entirely separate repositories. Product requirements live in Confluence or Google Docs. Test results live in yet another system.

Nobody opens each other’s tools. Ever. A mechanical engineer has no reason to learn Altium, and learning it wouldn’t help them do their job better. But this creates a structural condition: the dependency graph between decisions is implicit, distributed across human memory, and partially lossy at every handoff.

Why existing PLM/PDM systems don’t solve this. The obvious question: don’t tools like Teamcenter, Windchill, and Arena already exist for exactly this problem? Yes. And hardware teams use them. But PLM systems are record systems, not reasoning systems. They capture what was decided and when—revision history, approval workflows, BOM management. They don’t capture why a decision was made, what assumptions it depended on, or what other decisions would need to change if those assumptions became invalid.

The difference matters enormously. A record system tells you that Rev 3 of the chassis design was approved on March 15th. A reasoning system tells you that Rev 3 assumed a 100kg payload, and now that the customer wants 150kg, here are the 47 downstream decisions that may need revisiting. No PLM system does the second thing because the “why” was never captured in a structured format—it lived in meeting notes, Slack threads, and the heads of engineers who may have since left the company.

The graph that doesn’t exist. Here’s a mental model that makes the problem concrete: every hardware program has an implicit dependency graph connecting decisions to their upstream assumptions and downstream consequences. Change the payload spec, and that change propagates through battery sizing, chassis design, motor selection, thermal management, test protocols, and certification requirements.

In software, this graph is partially explicit—your build system knows what depends on what, your type checker catches some violations, your tests catch others. In hardware, this graph is almost entirely implicit. It exists only as distributed tribal knowledge across the team. When a senior engineer leaves, chunks of the graph leave with them. When a decision gets made in a meeting without documentation, edges in the graph become invisible.

Tangent: Why hasn’t hardware had its “git moment”? Software coordination was transformed by a handful of tools—git, CI/CD, type systems, package managers. These tools made the implicit explicit: dependencies became declarations, changes became trackable, integration became automated. Hardware has had 15+ years to develop equivalent tooling and... hasn’t. Why?

Part of it is the multi-tool problem—there’s no single artifact that captures a hardware design the way source code captures a software design. Part of it is the physics gap—you can’t unit test whether a part will crack under thermal stress the way you can unit test a function. But I suspect the deeper issue is that hardware’s dependency graph is fundamentally more complex and less formalizable. Software dependencies are logical—A imports B. Hardware dependencies are often physical and emergent—the thermal behavior of component A depends on its proximity to component B, which depends on the mechanical layout, which depends on the enclosure design.

This suggests that the “git for hardware” won’t look like git at all. It won’t be a version control system with better file format support. It’ll be something more like what Evercurrent is building—a reasoning layer that understands domain semantics rather than just tracking file changes.

Insight — AI can’t unlock productivity for hardware teams until someone makes the implicit dependency graph explicit. The tooling question is downstream of the knowledge architecture question. Evercurrent’s bet is that LLMs are finally capable enough to reconstruct and maintain this graph from the messy reality of how hardware teams actually work.

2. The Incentive Problem: Documentation as Organizational Debt

The Event — Ye made a point that should be obvious but rarely gets stated this clearly: hardware programs are aggressive, timelines are tight, and documentation is the first thing that gets cut. Nobody’s job is documentation. Nobody gets promoted because they kept specs in sync. The people who would benefit most from good documentation (future engineers, executives making tradeoff decisions) aren’t in the room when the documentation gets skipped.

This is a classic tragedy of the commons. The cost of skipping documentation is distributed across the organization and across time. The benefit of skipping documentation accrues immediately to the person who skipped it—they get to work on “real” work instead. Rational individual behavior produces irrational collective outcomes.

Hardware programs run 12-18 months. Assumptions made in month one—payload capacity, component specs, target certifications, thermal envelope—frequently change mid-program. Customer requirements evolve. Better components become available. Competitors force feature additions. Regulatory requirements shift.

When a customer says they need 150kg payload instead of 100kg, the correct response is: update the payload spec, trace all dependent decisions, notify affected teams, update test protocols, revise the certification timeline, and adjust the schedule accordingly.

The actual response is: have a meeting, assign the change to the relevant teams, hope everyone understands the implications, and move on. Maybe someone updates a spec doc. Maybe they don’t. Three months later, thermal testing fails because the motor selection assumed 100kg and nobody traced the dependency.

“The schedule never slips. We just cut features.” This line from Ye deserves its own analysis. It’s how organizations lie to themselves about execution quality. The schedule is a commitment to stakeholders. Features are internal decisions. By framing scope cuts as “prioritization” rather than “schedule slip,” teams maintain the narrative that they’re executing well while actually accumulating evidence that they’re not.

The problem: if you don’t understand why you had to cut features—which assumption changes cascaded into which delays, which dependencies were discovered late—you can’t improve. Your next program will repeat the same failure modes because you’ve erased the learning signal.

Ye’s point about post-mortems lands here: hardware teams find it nearly impossible to do meaningful retrospectives because the causal chain is unrecoverable. The decision that caused the problem might have been made six months ago by someone who’s since moved to a different team. The meeting where the assumption was established wasn’t documented. Nobody can reconstruct what happened, so nobody can learn from it.

The hero culture parallel. Software has the “10x engineer” myth—the person who ships features fast and fixes high-profile bugs becomes the hero. Hardware has the same dynamic but with higher stakes and longer feedback loops.

Ye described hardware engineers literally driving parts to airports to prevent production line stoppages. That’s a hero moment. But here’s the thing about hero moments: they’re symptoms of system failure. An organization that regularly requires heroics is an organization whose processes have failed. The hero is treating symptoms, not causes.

This creates a perverse incentive structure. The engineer who heroically saves the launch gets visibility and credit. The engineer who quietly maintains documentation and catches problems early gets... nothing. Their work is invisible precisely because it prevented the crisis that would have made someone else a hero.

Insight — The documentation problem isn’t a discipline problem or a tooling problem. It’s an incentive design problem. Any solution that requires humans to reliably do low-status work that benefits others more than themselves will fail. The only viable solutions either change the incentives or automate the work entirely. Evercurrent is betting on automation.

3. What Evercurrent Actually Does (And Why the Timing Is Now)

The Event — Evercurrent positions itself as an “AI operating platform” for hardware teams. Not a copilot for CAD. Not a chatbot that answers questions about your specs. An active system that monitors decisions, tracks changes, maintains the dependency graph, and surfaces problems before they become schedule slips.

The product thesis, decomposed:

Layer 1: Knowledge ingestion. Hardware teams have knowledge scattered across MCAD, ECAD, PLM, Jira, Confluence, Slack, email, and spreadsheets. Step one is connecting to these systems and building a unified representation of what the team knows. This is table stakes—every enterprise AI product does some version of this.

Layer 2: Decision extraction. Here’s where it gets interesting. Most enterprise AI stops at “search your docs.” Evercurrent is trying to extract not just information but decisions—what was decided, why, by whom, and what assumptions it depended on. This requires understanding the semantics of hardware development, not just the syntax of the documents.

Layer 3: Dependency tracking. Once you have decisions, you can start building the implicit dependency graph. Decision A (payload = 100kg) is upstream of Decision B (motor selection), which is upstream of Decision C (thermal design). When Decision A changes, the system can trace the implications forward.

Layer 4: Proactive monitoring. This is the “operating platform” part. The system doesn’t wait for you to ask questions—it watches for changes that might invalidate downstream decisions and alerts the relevant people. A change gets committed to the chassis design? The system checks whether that change is consistent with the thermal envelope assumptions and notifies the thermal team if it’s not.

Why now, specifically. Ye made the trust argument: hardware teams are skeptical of AI for organizational problems because they’ve been burned by overpromised enterprise software for decades. PLM systems were supposed to solve coordination. ERPs were supposed to integrate everything. Digital twins were supposed to simulate everything. Most of these promises underdelivered.

But something changed: the same skeptical hardware engineers now use ChatGPT in their personal lives. They’ve experienced AI that actually works for knowledge retrieval and synthesis. The gap isn’t “does AI work?”—they know it works—the gap is “does AI work for my organizational context?” That’s a much easier gap to close than convincing skeptics that AI is useful at all.

Tangent: The “unsexy infrastructure” pattern. There’s a category of startups that win by solving coordination problems everyone knows exist but nobody glamorizes. Stripe didn’t make payments exciting—they made them work. Twilio didn’t make SMS exciting—they made it programmable. Plaid didn’t make bank connections exciting—they made them reliable.

These companies share a pattern: they solve problems that are (a) genuinely painful, (b) understood to be painful by practitioners, but (c) not sexy enough to attract competition from people chasing flashier opportunities. “AI for hardware coordination” fits this profile perfectly. It’s not as exciting as “AI that designs products for you” or “generative design that creates novel geometries.” It’s plumbing. But plumbing that works is worth a lot.

The risk with unsexy infrastructure plays is that the sales cycle is long and the value is diffuse. You’re not selling “10x faster designs”—you’re selling “fewer surprises, fewer missed dependencies, better organizational learning.” That’s a harder ROI story to tell, even when the ROI is real.

The enterprise sales dynamic. Evercurrent sells top-down to executives and engineering directors. The users are individual engineers and program managers. This is the classic enterprise playbook—executive sponsor writes the check, ICs do the work.

The risk with this motion: mandated tools often fail because the people forced to use them don’t see the value. The tools that win in enterprise are usually tools that ICs adopt voluntarily and then spread organically (Slack, Notion, Figma).

Evercurrent’s counter: the value prop to ICs is “we automate the tedious coordination work you hate.” If the system actually delivers on that—less time in status meetings, less time chasing updates, less time writing documentation—adoption follows. The exec mandate gets you in the door; the IC experience determines whether you stay.

Insight — The timing thesis isn’t just “LLMs are good enough now.” It’s “hardware engineers have been pre-sold on AI through consumer products, and enterprise AI tooling has matured enough to handle the integration complexity of multi-system environments.” The window opened recently and won’t stay open indefinitely—whoever captures the institutional knowledge first has a durable advantage.

4. The Competitive Advantage That Compounds

The Event — The conversation surfaced an underappreciated point about institutional knowledge: it compounds. The team that gets their knowledge together doesn’t just execute faster on this product—they execute faster on every subsequent product.

Why hardware knowledge is a compounding asset. Software knowledge depreciates rapidly. The framework you mastered three years ago might be obsolete. The architecture patterns that were best practice in 2020 might be antipatterns now. Software engineers are on a treadmill—constantly learning new things because the old things stop being relevant.

Hardware knowledge depreciates much more slowly. The physics of thermal management, the tradeoffs in motor selection, the failure modes of specific connector types—this knowledge stays relevant for decades. A senior hardware engineer’s experience from 2010 is still valuable in 2026 in a way that a senior software engineer’s 2010 experience often isn’t.

This means institutional knowledge in hardware is more valuable than in software, not less. The company that successfully captures and operationalizes their senior engineers’ tacit knowledge has a durable asset. The company that loses it when those engineers retire or leave is starting from scratch.

The death spiral of tribal knowledge. Here’s the failure mode Ye is implicitly addressing: Hardware team has senior engineers with deep tacit knowledge. Company doesn’t invest in knowledge capture because the senior engineers are “still here.” Senior engineers start retiring or leaving. Remaining team realizes they don’t know why half their design decisions were made. Development velocity craters because every decision requires rediscovering constraints that used to be common knowledge. Company loses competitive position to rivals who didn’t lose their institutional memory.

This is happening right now at established hardware companies. The engineers who designed the first generation are aging out. Their replacements inherited the designs but not the reasoning. The “we’ve always done it this way” answer stops being sufficient when market conditions change and you need to know why you did it that way.

Tangent: Toyota figured this out decades ago. The Toyota Production System is famous for manufacturing efficiency, but its deeper insight was about institutional learning. Practices like the A3 report—a structured one-page problem-solving document—weren’t just bureaucracy. They were mechanisms for capturing why decisions were made, what alternatives were considered, and what assumptions would need to be true for the decision to remain valid.

Toyota’s system was human-powered and high-overhead. It worked because Toyota built a culture that valued the learning process, not just the outcome. Most companies can’t replicate that culture. They try to adopt Toyota’s tools without adopting Toyota’s values, and the tools become empty rituals.

The AI version of this might finally make institutional learning scalable without requiring cultural transformation. You don’t need engineers to adopt A3 discipline if the system is reconstructing the decision context from their normal workflow artifacts. The Toyota insight was correct—capturing decision reasoning is valuable—but the implementation mechanism becomes automation rather than culture.

The new entrant advantage. Conversely, new entrants in hardware markets—robotics startups, drone companies, EV upstarts—have an interesting opportunity. They don’t have legacy institutional knowledge to capture, but they also don’t have legacy knowledge debt. If they build with knowledge capture as a first-class concern from day one, they can accumulate institutional memory at a rate that established players can’t match.

This is the “two types of teams” dynamic Ye mentioned at CES: hardware veterans who lack AI/software integration experience, and software people who don’t understand hardware constraints. The team that figures out how to combine both—hardware intuition with modern knowledge management—wins.

Insight — In hardware, institutional memory is a moat. Unlike software where the game is speed-to-market and rapid iteration, hardware competition is increasingly about who can learn faster across product generations. The company that can say “we tried that approach in 2019 and here’s why it didn’t work” executes faster than the company that has to rediscover that lesson.

5. Physical AI and the Synthesis Premium

The Event — The conversation turned to who thrives in this environment. Ye’s answer: people who can integrate deep domain knowledge across multiple disciplines. Not specialists who go infinitely deep on one thing, but synthesizers who understand how decisions in one domain constrain options in another.

Why physical AI is different from software AI. In software, the trend has been toward specialization. Frontend, backend, infrastructure, ML, data—each domain has gotten deep enough that generalists struggle to keep up. The “full-stack developer” of 2010 is increasingly a myth in 2026.

Physical AI reverses this trend. When you’re building robots, drones, or wearables, the integration layer is the product. The mechanical design constrains the electrical layout, which constrains the thermal management, which constrains the software architecture, which constrains the user experience. You can’t optimize any single domain without understanding how it affects the others.

The implication: the talent bottleneck in physical AI isn’t “people who can do X”—it’s “people who can hold multiple Xs in their head simultaneously and reason about their interactions.” This is a different skill profile than what most technical hiring optimizes for.

The apprenticeship model prediction. Ye made an interesting claim about the future of learning: people won’t learn primarily by reading documentation—they’ll learn by doing, with AI supplementing knowledge in real-time based on their execution context.

This is how senior engineers teach juniors now. The junior doesn’t read a manual on thermal management; they work on a thermal problem while the senior provides context, catches mistakes, and explains the reasoning behind design choices. The limitation is that senior time doesn’t scale and isn’t available at 2am when the junior is debugging alone.

The AI version of this is contextual knowledge delivery: the system understands what you’re working on and surfaces relevant institutional knowledge at the point of need. “You’re modifying the cooling system—here’s what the team learned when we tried a similar approach in the previous generation.”

This isn’t chatbot Q&A. It’s proactive, context-aware knowledge augmentation. The system knows what you’re doing, knows what the organization knows, and bridges the gap without you having to ask the right question.

Insight — The talent advantage in physical AI goes to synthesizers who can hold multiple domain models in their head simultaneously. But “synthesizer” is about to become a learnable skill rather than an innate trait. The AI systems that make institutional knowledge accessible transform synthesis from “rare talent” to “trainable capability.” This is good news for organizations and bad news for people whose value proposition was “I’m the only one who understands how all the pieces fit together.”

6. The Simulation Endgame

The Event — I asked whether Evercurrent’s position—tracking decisions, dependencies, and changes across the lifecycle—naturally leads to simulation capabilities. If you understand how a system’s decisions interconnect, can you start asking “what if” questions?

Ye’s answer: yes, but sequenced. The prerequisite for useful simulation is having the decision context in a structured format. Most hardware teams don’t have that. Their institutional knowledge is scattered across tools, tribal memory, and stale documentation. You can’t simulate tradeoffs on a system you don’t have a coherent model of.

The roadmap implication: knowledge consolidation first, scenario planning second. This sequences correctly—you’re not trying to boil the ocean on day one.

What simulation means in this context. When people hear “simulation for hardware,” they usually think physics simulation—FEA, CFD, thermal modeling. That’s not what we’re talking about. The simulation Ye is describing is decision consequence modeling: if we change assumption X, what decisions become invalid? If we’re considering options A, B, and C, what are the downstream implications of each?

This is a different kind of simulation. It’s not about computing physical properties—it’s about computing organizational and technical dependencies. What happens to our certification timeline if we change the battery chemistry? What happens to our cost model if we switch suppliers? What decisions have we made that assumed the old supplier’s lead times?

The executive decision support use case. Hardware executives constantly make cost-time-quality tradeoffs with incomplete information. The current state of the art: red/yellow/green spreadsheets aggregated by humans with a two-week delay. The “yellow” from the mechanical team might mean “minor concern we’re tracking” while “yellow” from the electrical team means “we’re going to miss the milestone.”

The promise of decision simulation: executives can actually model second-order effects before committing. “If we cut this feature, what does that unblock downstream?” “If we slip this milestone, what certifications do we jeopardize?” “If we accept this customer requirement change, what’s the actual cost in schedule and engineering hours?”

Today, these questions get answered by convening meetings, polling team leads, and synthesizing their intuitions. That process is slow, lossy, and biased by whoever is most confident or most senior. Decision simulation could make it fast, complete, and evidence-based.

Tangent: This is what financial modeling did for business decisions. Before spreadsheets, business planning was qualitative. Executives made decisions based on intuition and experience because modeling the financial implications of different scenarios was prohibitively expensive. VisiCalc and Lotus 1-2-3 changed that—suddenly you could ask “what if we raise prices 10%?” and see the P&L implications instantly.

Hardware decision modeling could be the equivalent shift for product development. Right now, asking “what if we change the payload spec?” requires convening meetings and polling experts. The answer comes back in days or weeks, if it comes back coherently at all. A system that can trace decision dependencies and model implications could make that answer available in minutes.

The analogy isn’t perfect—financial models have clean quantitative relationships, while hardware dependencies are messier and more qualitative. But the directional shift is the same: from “decisions based on intuition because modeling is too expensive” to “decisions informed by explicit models because the cost of modeling dropped by orders of magnitude.”

Insight — The simulation endgame for hardware AI isn’t physics—it’s decision consequence modeling. The bottleneck is structured institutional knowledge, not compute. The company that can model “what happens if we change X” across their entire decision graph has a fundamentally different relationship with uncertainty than competitors who have to guess.

Key Takeaways for Builders

If you’re building in physical AI:

Treat knowledge architecture as a first-class concern from day one. Don’t assume you’ll “figure out documentation later.” The companies that win in hardware win partly because they can learn across product generations. That requires capturing not just what you decided but why.

Hire for synthesis, not just depth. The integration layer is the product. People who can reason across mechanical, electrical, firmware, and software domains are more valuable than deep specialists in any single domain—and rarer.

Watch for the PLM trap. Traditional PLM systems capture records, not reasoning. Don’t mistake having a system for having solved the knowledge problem. If your team can’t answer “why did we make that decision,” your PLM isn’t helping.

If you’re evaluating hardware AI tools:

Ask about the dependency graph. Any tool can do RAG over your documents. The differentiated tools are the ones that understand the structure of hardware decisions—what depends on what, how changes propagate, where the implicit assumptions live.

The timing is better than it looks. Hardware teams are skeptical of enterprise software, but they’ve already adopted AI personally. The objection isn’t “AI doesn’t work”—it’s “AI doesn’t work for my specific context.” That’s a surmountable objection.

If you’re a hardware engineer:

Your tacit knowledge is more valuable than you think. The “why” behind decisions—the constraints you’ve internalized, the failure modes you’ve seen, the tradeoffs you make instinctively—is irreplaceable institutional knowledge. Companies will increasingly compete for people who can articulate and transfer that knowledge.

The synthesis premium is rising. The engineer who only knows one domain is increasingly commoditized. The engineer who can trace implications across domains—”if we change the motor, here’s what happens to thermal, power, and certification”—commands a premium that will only grow as systems get more integrated.

Once again, apply for a role at EverCurrent over here and reach out to Ye if her work might interest you.

Subscribe to support AI Made Simple and help us deliver more quality information to you-

Flexible pricing available—pay what matches your budget here.

Thank you for being here, and I hope you have a wonderful day.

Dev <3

If you liked this article and wish to share it, please refer to the following guidelines.

That is it for this piece. I appreciate your time. As always, if you’re interested in working with me or checking out my other work, my links will be at the end of this email/post. And if you found value in this write-up, I would appreciate you sharing it with more people. It is word-of-mouth referrals like yours that help me grow. The best way to share testimonials is to share articles and tag me in your post so I can see/share it.

Reach out to me

Use the links below to check out my other content, learn more about tutoring, reach out to me about projects, or just to say hi.

Small Snippets about Tech, AI and Machine Learning over here

AI Newsletter- https://artificialintelligencemadesimple.substack.com/

My grandma’s favorite Tech Newsletter- https://codinginterviewsmadesimple.substack.com/

My (imaginary) sister’s favorite MLOps Podcast-

Check out my other articles on Medium. :

https://machine-learning-made-simple.medium.com/

My YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/@ChocolateMilkCultLeader/

Reach out to me on LinkedIn. Let’s connect: https://www.linkedin.com/in/devansh-devansh-516004168/

My Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/iseethings404/

My Twitter: https://twitter.com/Machine01776819