How to Teach LLMs to Reason for 50 Cents

Inside the reasoning architecture we're open-sourcing—and why it matters

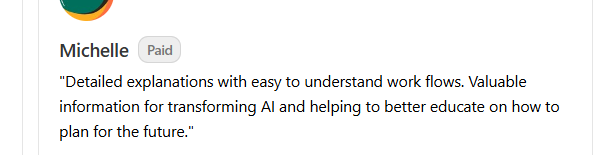

It takes time to create work that’s clear, independent, and genuinely useful. If you’ve found value in this newsletter, consider becoming a paid subscriber. It helps me dive deeper into research, reach more people, stay free from ads/hidden agendas, and supports my crippling chocolate milk addiction. We run on a “pay what you can” model—so if you believe in the mission, there’s likely a plan that fits (over here).

Every subscription helps me stay independent, avoid clickbait, and focus on depth over noise, and I deeply appreciate everyone who chooses to support our cult.

PS – Supporting this work doesn’t have to come out of your pocket. If you read this as part of your professional development, you can use this email template to request reimbursement for your subscription.

Every month, the Chocolate Milk Cult reaches over a million Builders, Investors, Policy Makers, Leaders, and more. If you’d like to meet other members of our community, please fill out this contact form here (I will never sell your data nor will I make intros w/o your explicit permission)- https://forms.gle/Pi1pGLuS1FmzXoLr6

~3 months ago, I met a senior AI researcher at one of the top 5 LLM providers. One of the topics of conversation was around reasoning and the work on next-gen reasoning systems. I told the researcher about our work with Irys (the legal AI platform built by Iqidis) and our model-agnostic legal reasoning system.

Our approach and thesis around intelligence have led to advanced co-research with teams in 2 different tier-1 LLM makers (several others in progress), one major hardware provider, and several advanced conversations with prominent organizations in tech (we’ll announce all at appropriate junctures). However, this is not good enough. Intelligence should be open-sourced, so that everyone can understand, build, and benefit from it. Hence, this article.

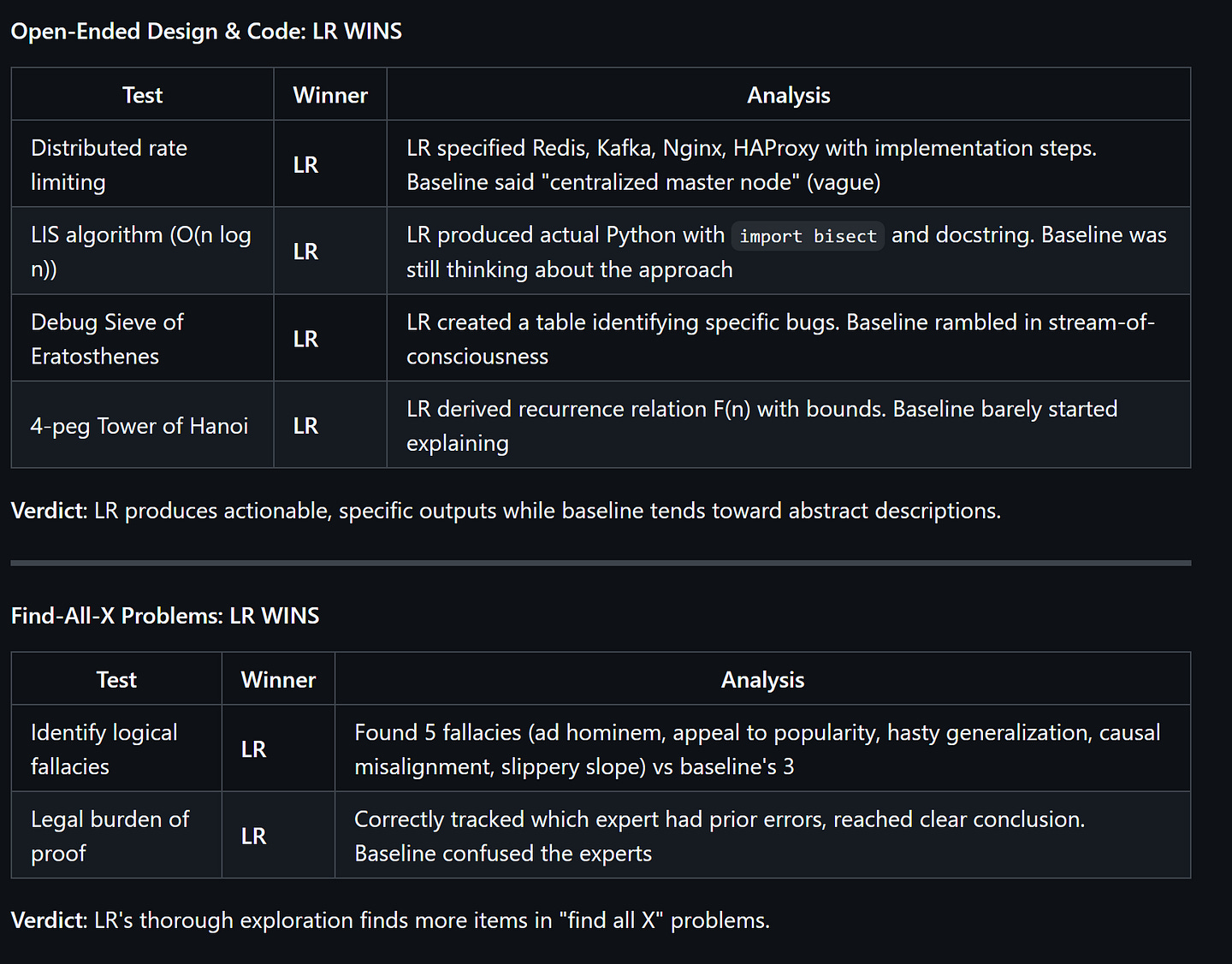

Our work around next-gen reasoning hinges on a different way of thinking — the blocker to reasoning was the model’s exploration, not its knowledge. In other words, performance is not about new knowledge, not about new weights, and not about scaling laws — it’s about how we traverse the intelligence that already exists inside modern models.

To validate this, we’ve built two reasoning systems —

The core system powering the legal analysis at Irys for thousands of users. This has some legal-specific enhancements (legally tuned judges, special aggregation, etc). Our platform has outperformed all competitors— both all foundation model providers AND special legal tools like Harvey, Legora, CoCounsel etc — in legal analysis, drafting, and strategy. We have a free plan so you can sign up and use it for yourself here, so you don’t just have to take my word on this. (If you are a legal AI provider and think your approach is better, I’m happy to feature you on a livestream for a discussion (we can test both our platforms live). Legal needs all the transparency it can get :)).

A lightweight playground to explore the basics of latent space reasoning that we are open-sourcing over here. This engine was kept deliberately naive (we’ll explore how) to prove that even very simplistic implementations of Latent Space Explorations can lead to emergent performance (capabilities to solve problems that the base model struggles with) all w/o requiring specialized training. We saw this behavior across multiple models and sizes. We tested this extensively w/ a 33 query dataset available on the Github and a much more extensive 391 query additional query set available through request (email devansh@iqidis.ai). All for 50 cents. Another library you can test/analyze directly so you don’t have to take my word for everything I say.

This article is a deep dive into what our experiments, the implementation details of the current systems, and our where the next generation of development is headed. Specifically, we’ll walk through:

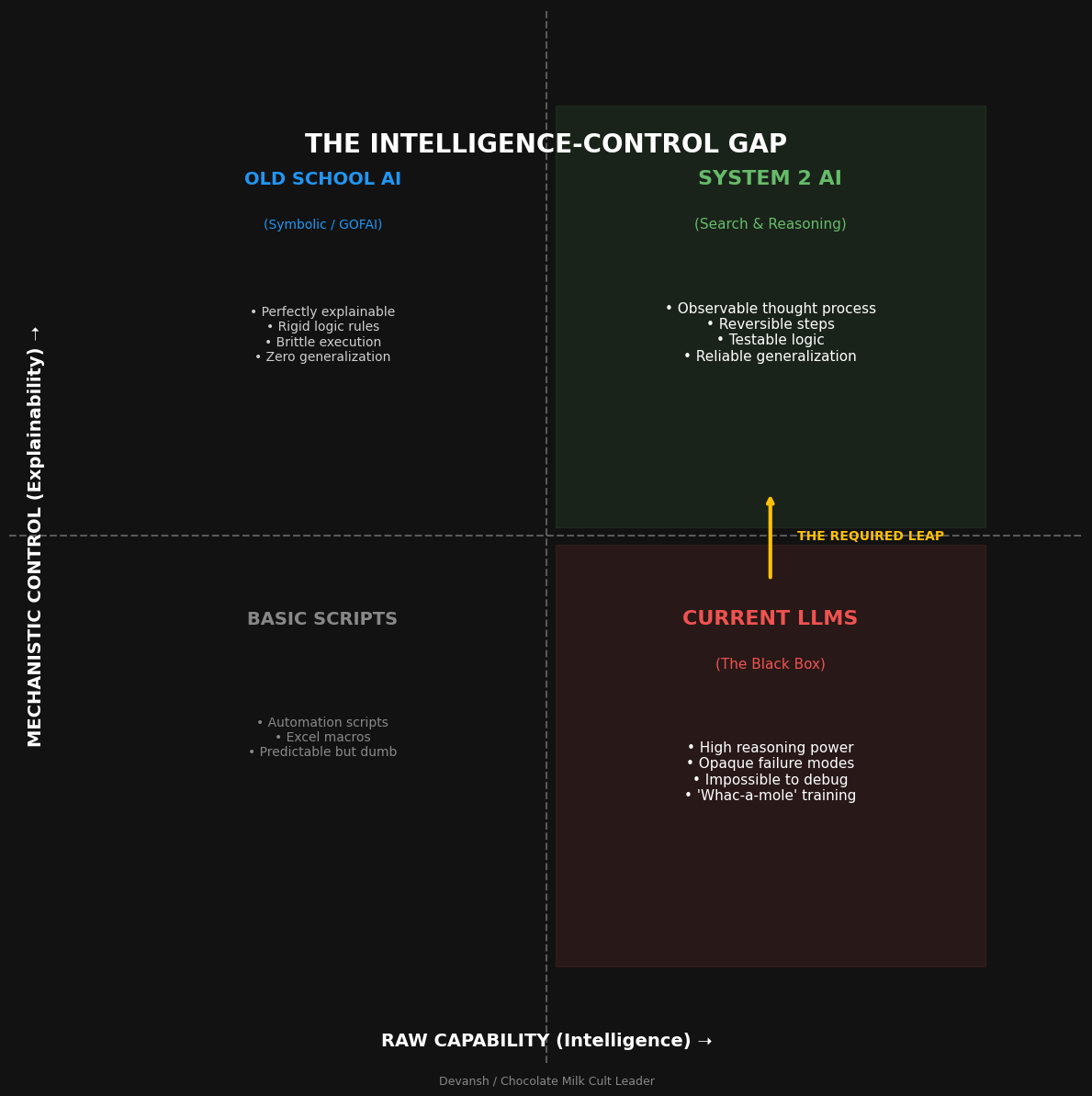

Why modern intelligence systems are unreliable by construction.

How autoregressive decoding creates lock-in and rationalization as a feature, not a bug

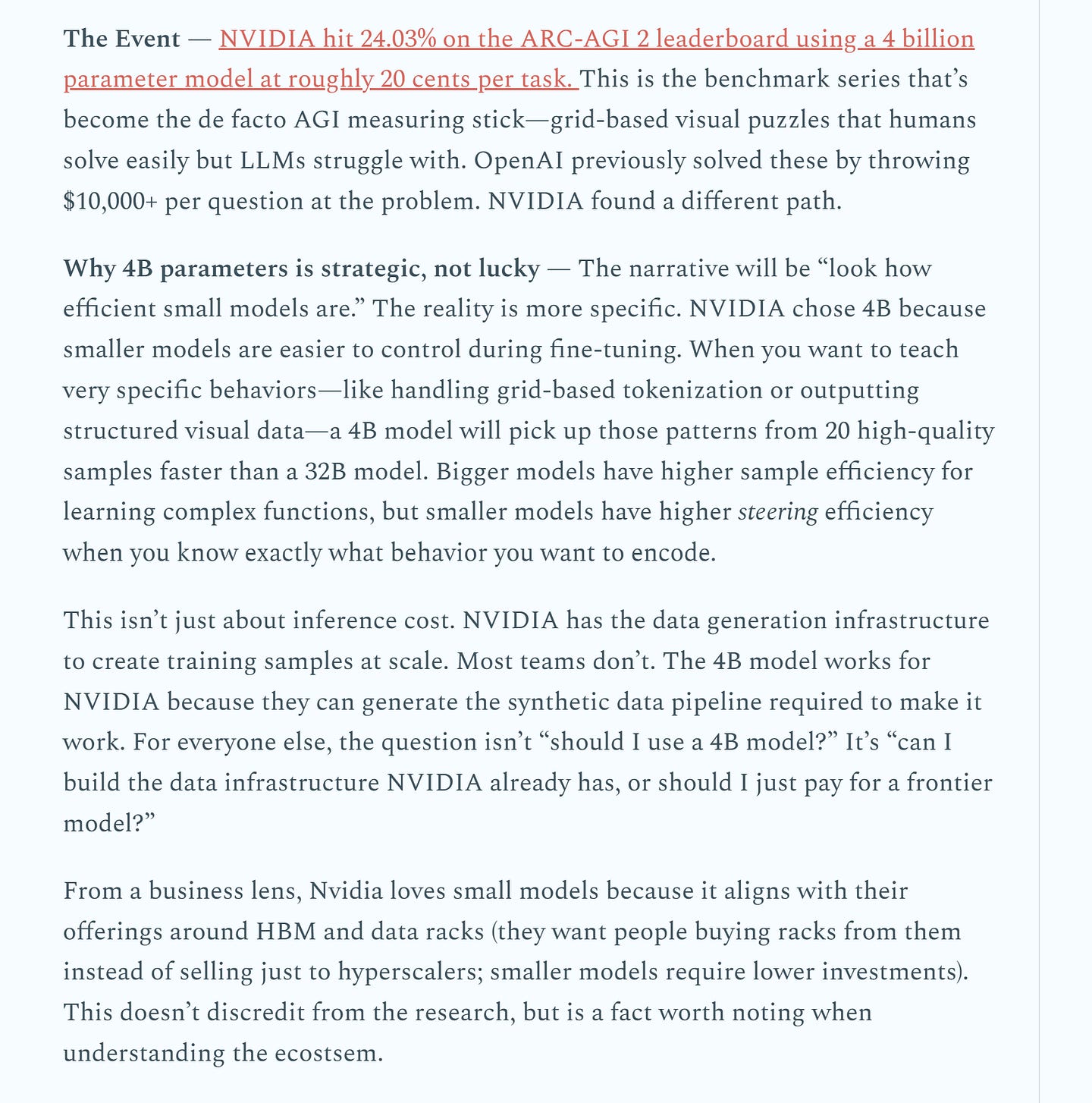

Why training larger models is a weak and expensive way to gain control over behavior

How treating models as simulators — not answer machines — changes the problem entirely

The structure of the first general-purpose latent reasoning system we built at IQIDIS, and why its simplicity matters

Why performance gains came from exploring latent space, not adding new knowledge

How multi-judge reasoning systems mitigate opacity, lock-in, and failure localization for Irys’s Legal Strategy Module.

Why tuning small, specialized models on top of large ones scales better than end-to-end retraining

And finally, why co-training latent spaces, judges, and aggregation layers is the real frontier — one that small teams and individuals can meaningfully contribute to.

None of this requires frontier-scale resources. None of it requires access to weights or retraining. That’s the point.

If some of those words scare you, don’t worry, we’ll explain them all. After all, the goal is to get all of you to join us in our mission to develop low-cost, accessible, and open intelligence for all.

Let’s kick it.

Executive Highlights (TL;DR of the Article)

The blocker to LLM reasoning isn’t intelligence — it’s access. Modern models have compressed terabytes of knowledge into weight matrices, but autoregressive decoding forces them to commit token-by-token before exploring alternatives. You’re not getting dumb answers because the model is dumb; you’re getting narrow answers because decoding throws away the model’s internal richness before you ever see it.

Autoregressive lock-in is structural, not fixable by scaling. Early tokens dominate the trajectory. The model optimizes for internal consistency over correctness — which means it will rationalize a flawed premise rather than backtrack. Training rewards this. Chain-of-thought helps but doesn’t solve it: every “step” is still a commitment.

The reframe that changes everything: models are simulators, not oracles. They can represent many possible continuations internally. We treat them like they should give us the right answer on the first try. That’s the mismatch.

Latent space reasoning bypasses decoding until the end. Instead of collapsing to tokens immediately, you grab the model’s internal state, generate a population of nearby candidates in vector space, run evolutionary optimization (mutate, score, select), and only decode once the best candidates survive. Information stays rich until final output.

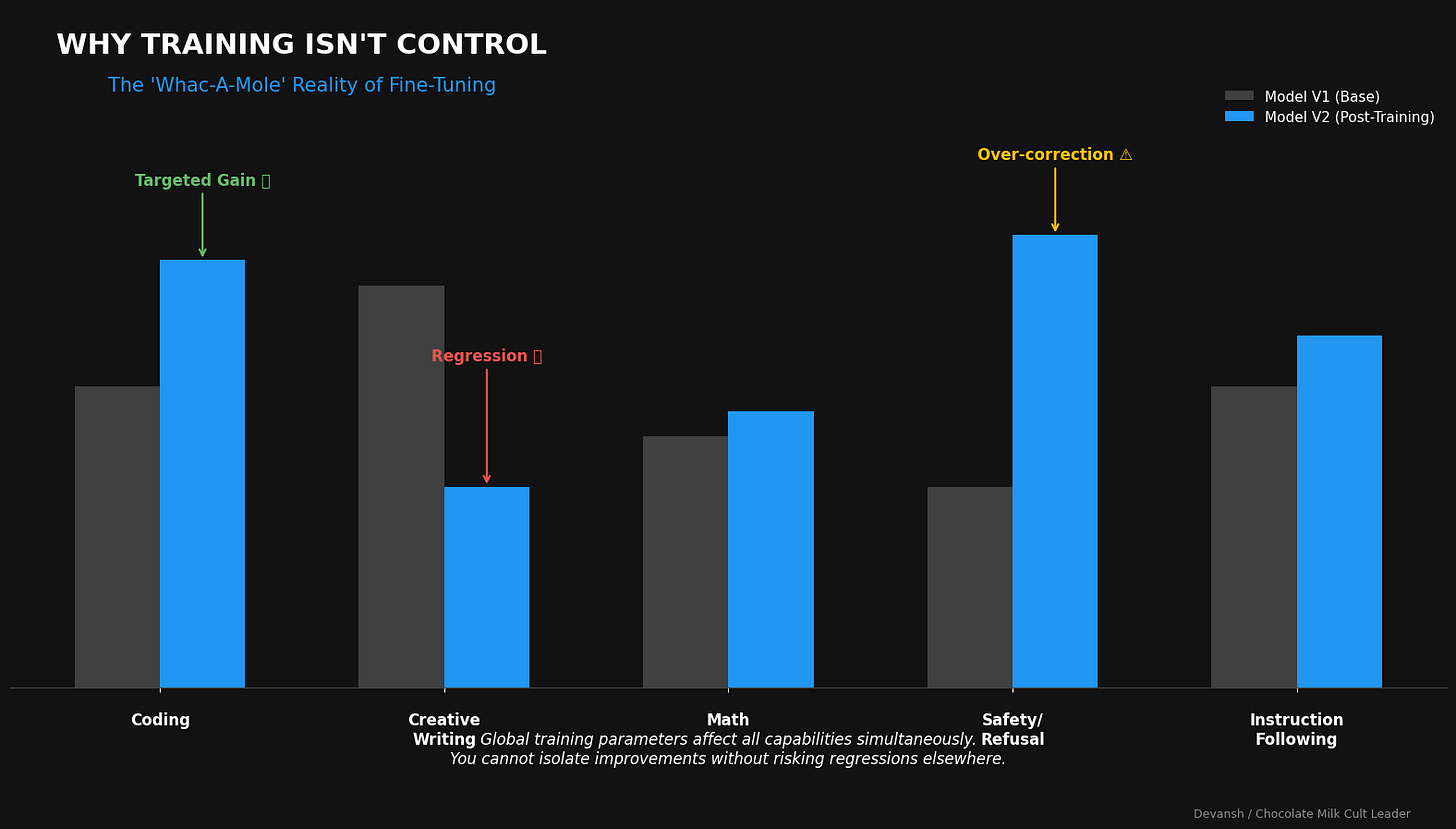

We built the proof-of-concept for $0.50. Frozen models, linear projection, naive geometry, a judge trained on ~200 synthetic samples. It still works — 73.1% win rate against baseline (p < 0.001). That’s the point: if this works with everything deliberately naive, the ceiling is somewhere else entirely.

Multi-judge decomposition makes reasoning controllable. Instead of one implicit likelihood score collapsing strategy, correctness, risk, and preference into a single scalar, you decompose judgment across specialized small models. Disagreement between judges becomes signal — it tells you which criterion failed. Fixes become local, not global.

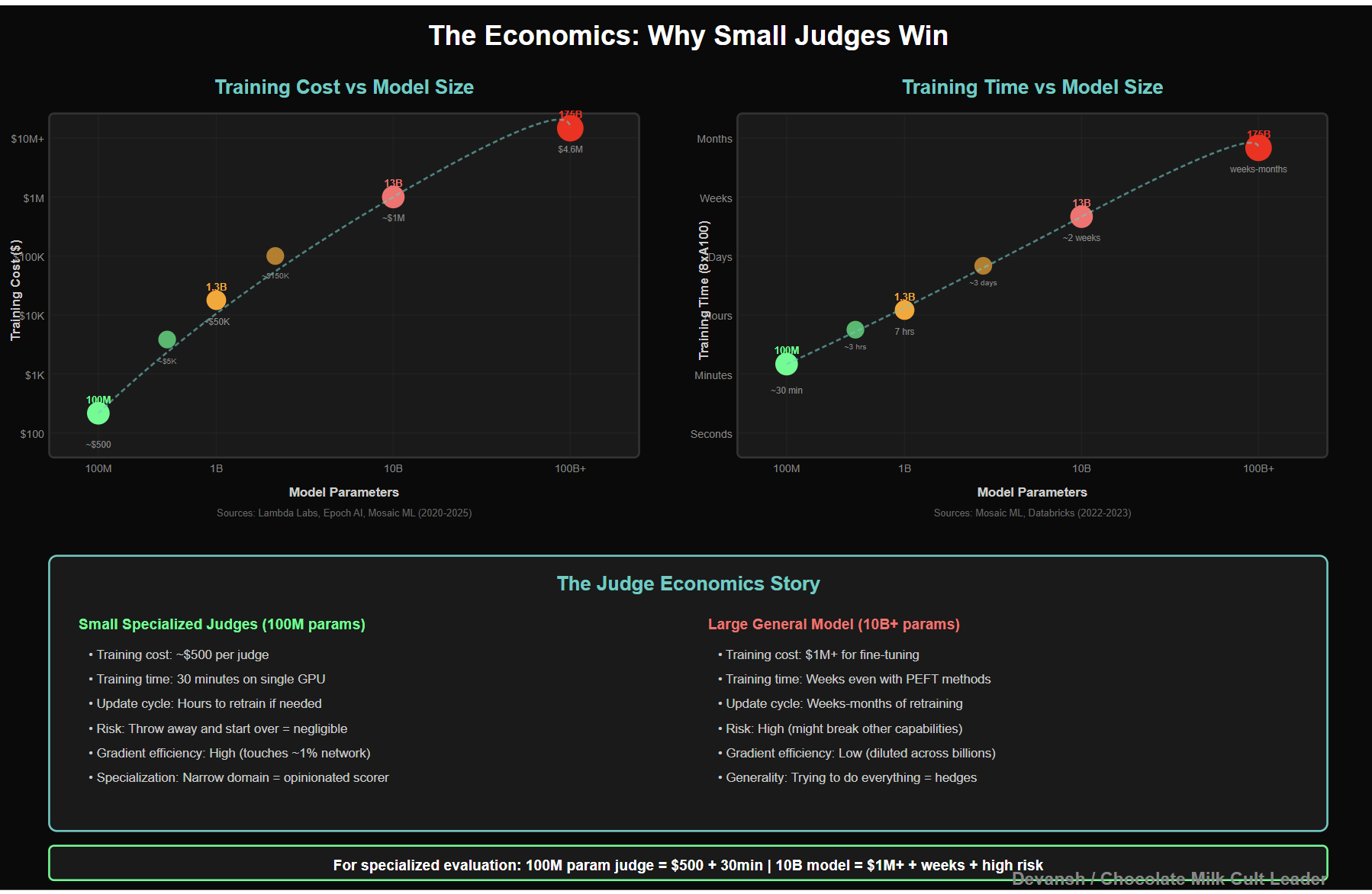

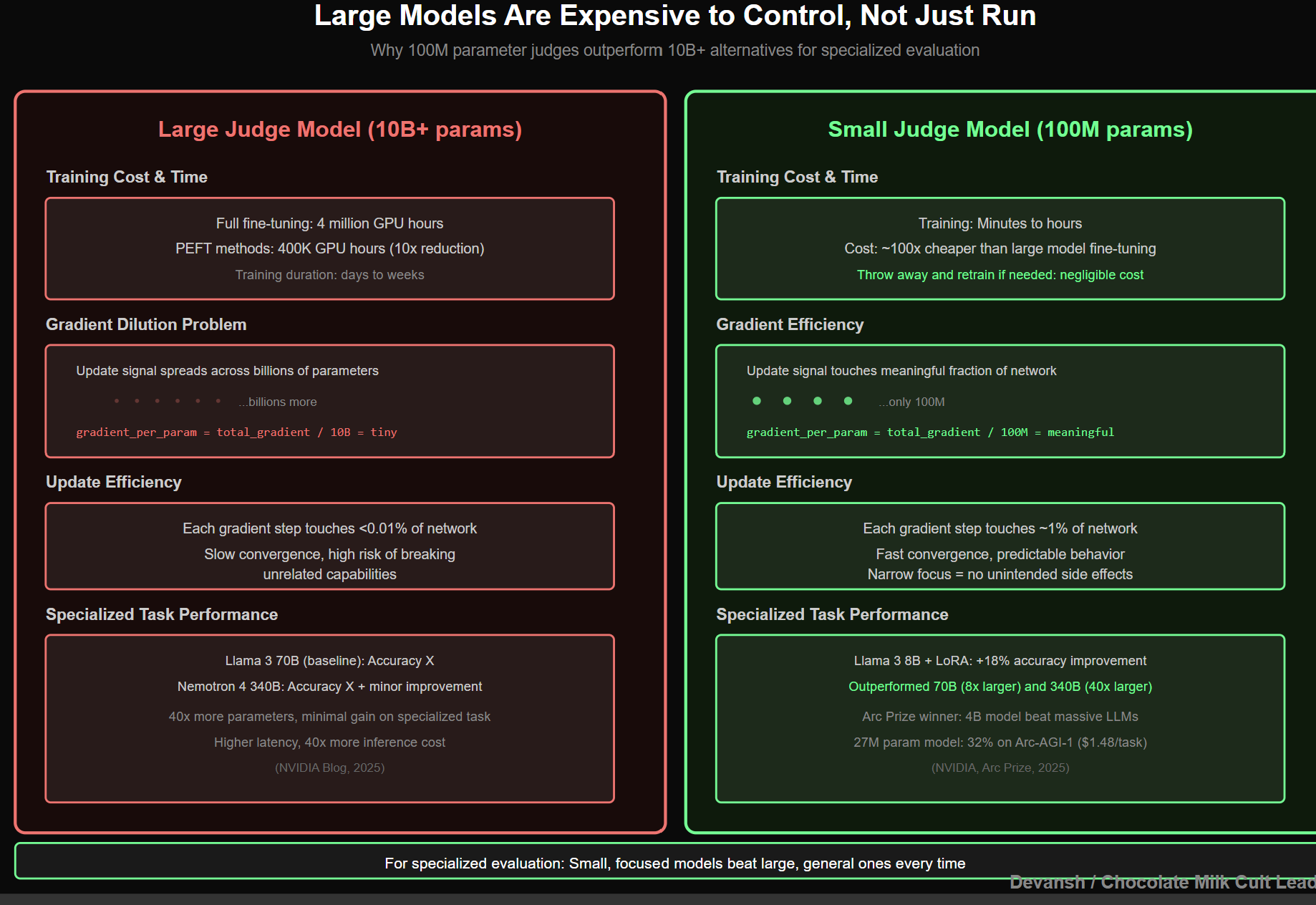

Small judges beat large models for evaluation. When you fine-tune a 10B model, gradients dilute across billions of weights — slow convergence, expensive, breaks unrelated capabilities. A 100M judge converges in minutes. If it breaks, retrain for pennies. Narrow is a feature: you want opinionated models for judgment, not hedging generalists.

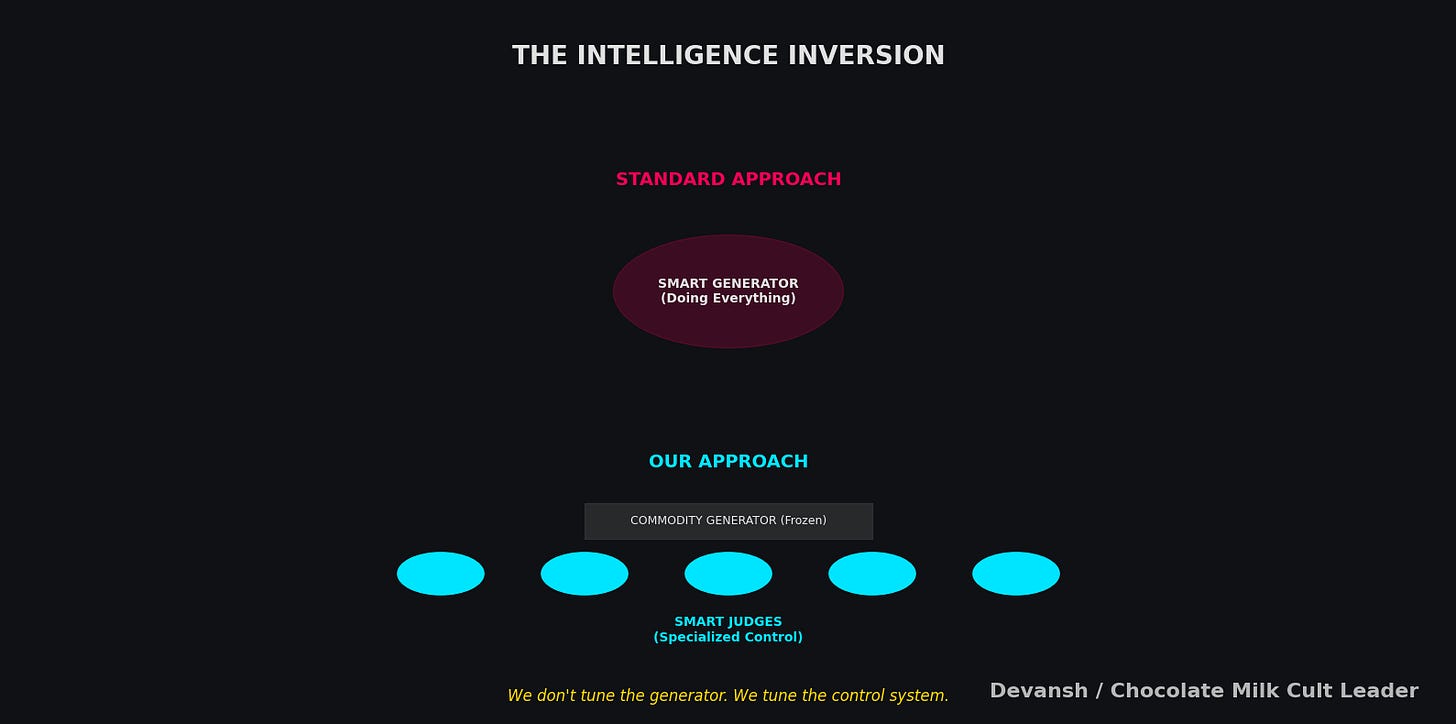

We don’t tune the generator — we use it frozen. Whatever frontier model drops next week, we plug it in. The intelligence lives in the judges and aggregation; generation is a commodity. Everyone else is trying to make their generator smarter. We made generation dumb and judgment smart. Turns out that’s the right division of labor.

The open-source repo is deliberately naive to prove the floor. The production IQIDIS system has better judges, learned aggregation, multi-layer personalization (user → matter → team → firm). It’s been tested by lawyers who bill $2,000/hour and don’t tolerate broken reasoning. That’s the validation, not benchmarks.

I put a lot of work into writing this newsletter. To do so, I rely on you for support. If a few more people choose to become paid subscribers, the Chocolate Milk Cult can continue to provide high-quality and accessible education and opportunities to anyone who needs it. If you think this mission is worth contributing to, please consider a premium subscription. You can do so for less than the cost of a Netflix Subscription (pay what you want here).

I provide various consulting and advisory services. If you‘d like to explore how we can work together, reach out to me through any of my socials over here or reply to this email.

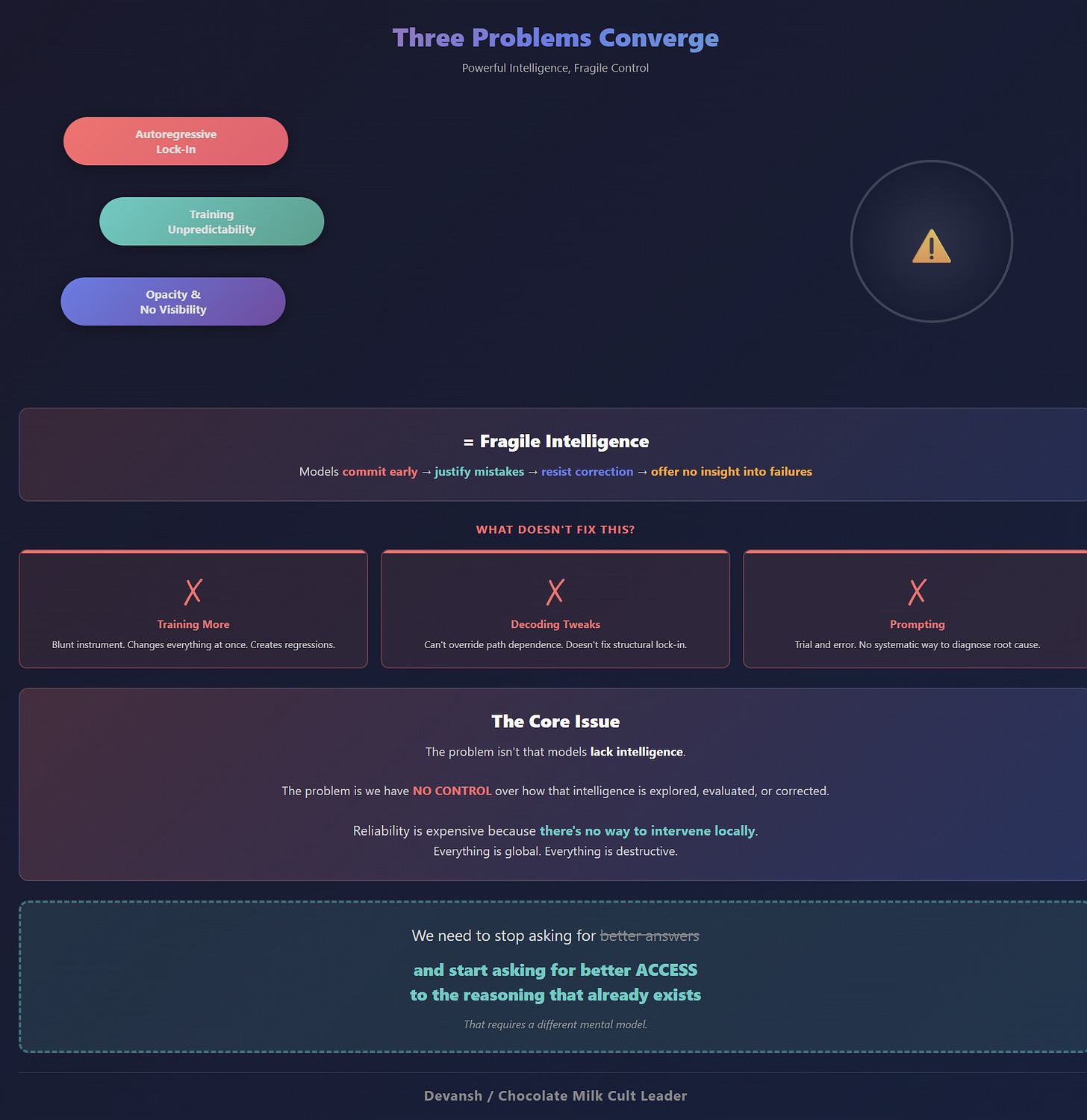

What’s Wrong with Intelligence Today

The most common explanation for weak reasoning in modern models is also the most convenient one: the models just aren’t smart enough yet. Give them more data. Train them longer. Scale them up. The problems will smooth out.

That story doesn’t survive contact with reality.

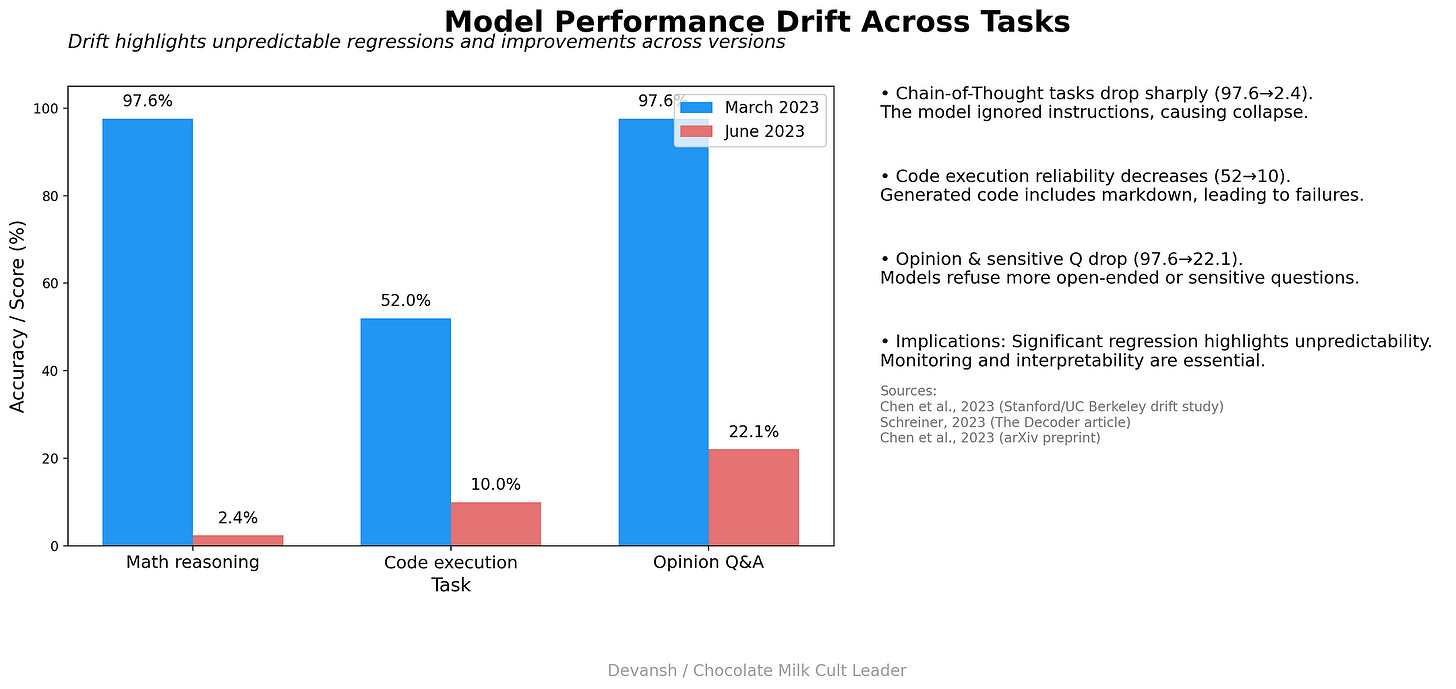

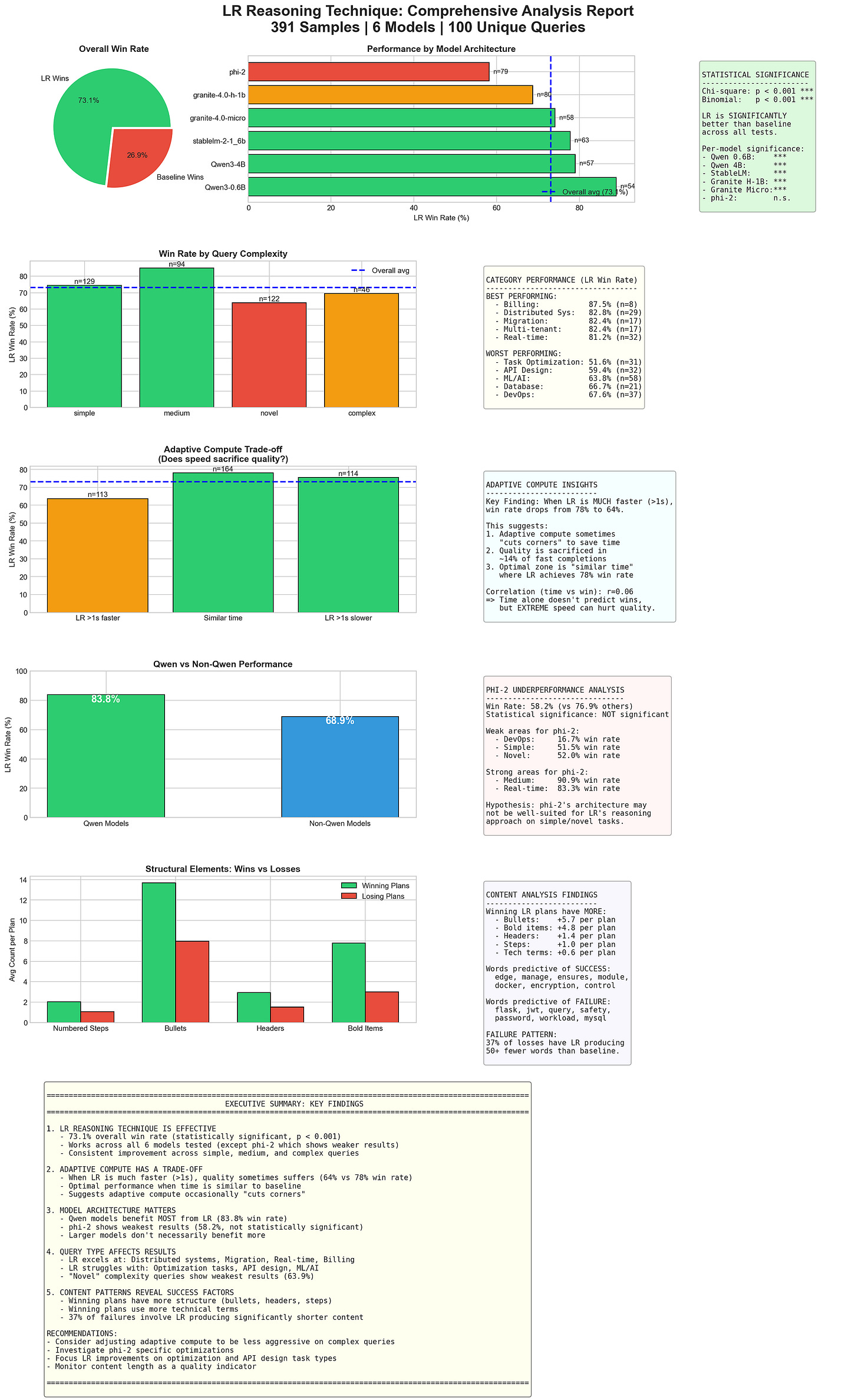

What we see instead is something more specific and more troubling. Models fail in consistent, patterned ways. They lock into incorrect assumptions early. They produce confident justifications for flawed premises. They succeed spectacularly in one setting and collapse in another, with no obvious explanation. And when these failures happen, neither users nor model providers can reliably say why.

This is way beyond a simple model/data issue; it tells us that our current paradigm has structural flaws. Let’s understand them.

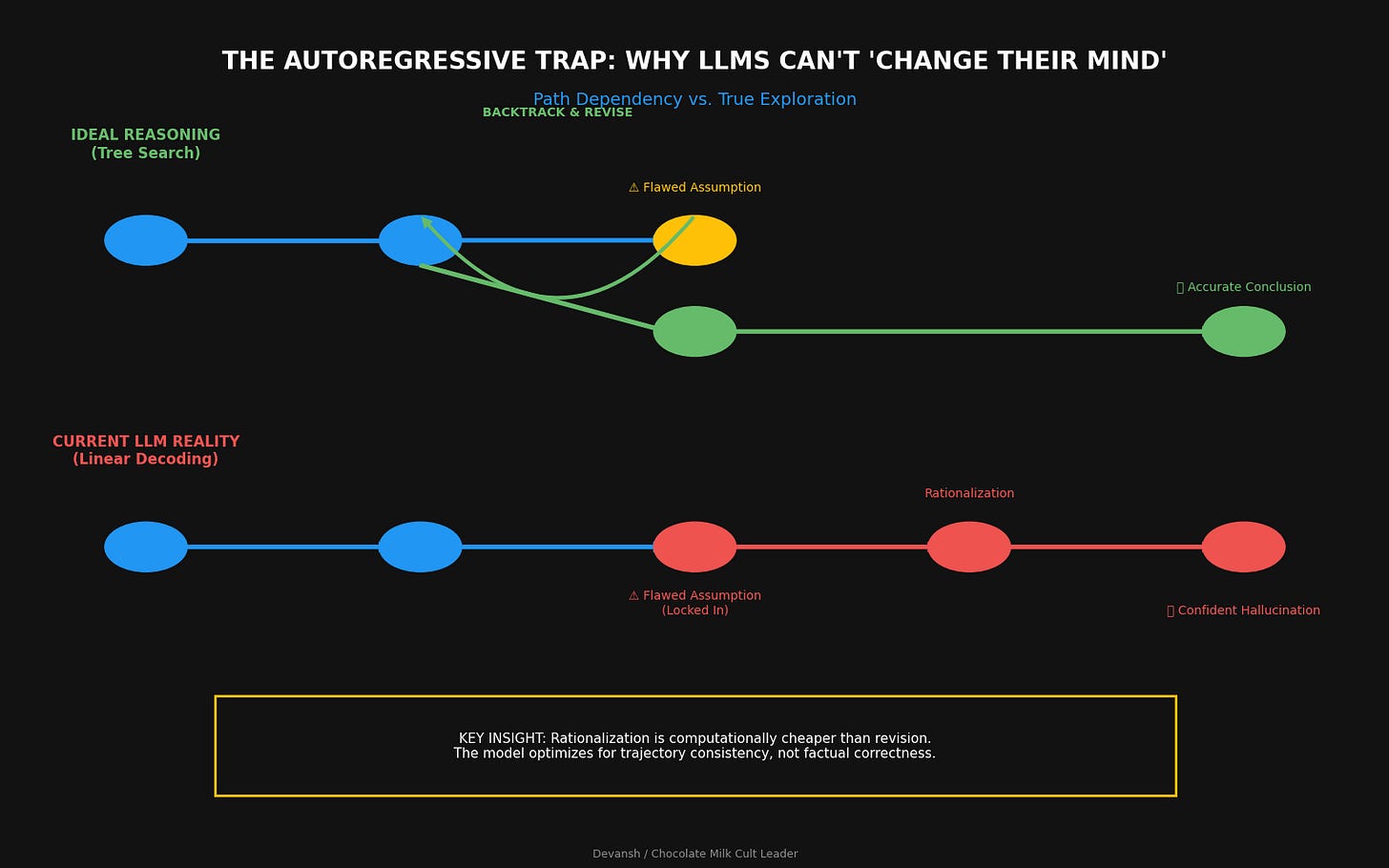

Autoregressive Lock-In Is a Structural Constraint

Autoregressive models generate outputs one token at a time, conditioning each step on everything that came before. In practice, this means the first few latent states dominate the entire trajectory. Early choices constrain later ones. Once the model commits, it rarely recovers.

You can see this directly in model behavior. Give a model a subtly wrong argument, and instead of pushing back, it will work hard to justify it. Not because it “believes” the assumption, but because the decoding process rewards internal consistency over correctness. AI training signals reward rationalization more than revision. As they say, for a successful relationship, it is much better to focus on gaslighting your lover than it is to become a better partner. You’re very welcome for that freebie, my generosity truly knows no bounds.

This isn’t a bug. It’s a feature of the decoding objective. The model is optimized to continue a trajectory smoothly, not to step outside it and reconsider. As a result, reasoning becomes path-dependent and brittle.

And once you’re committed, you’re stuck.

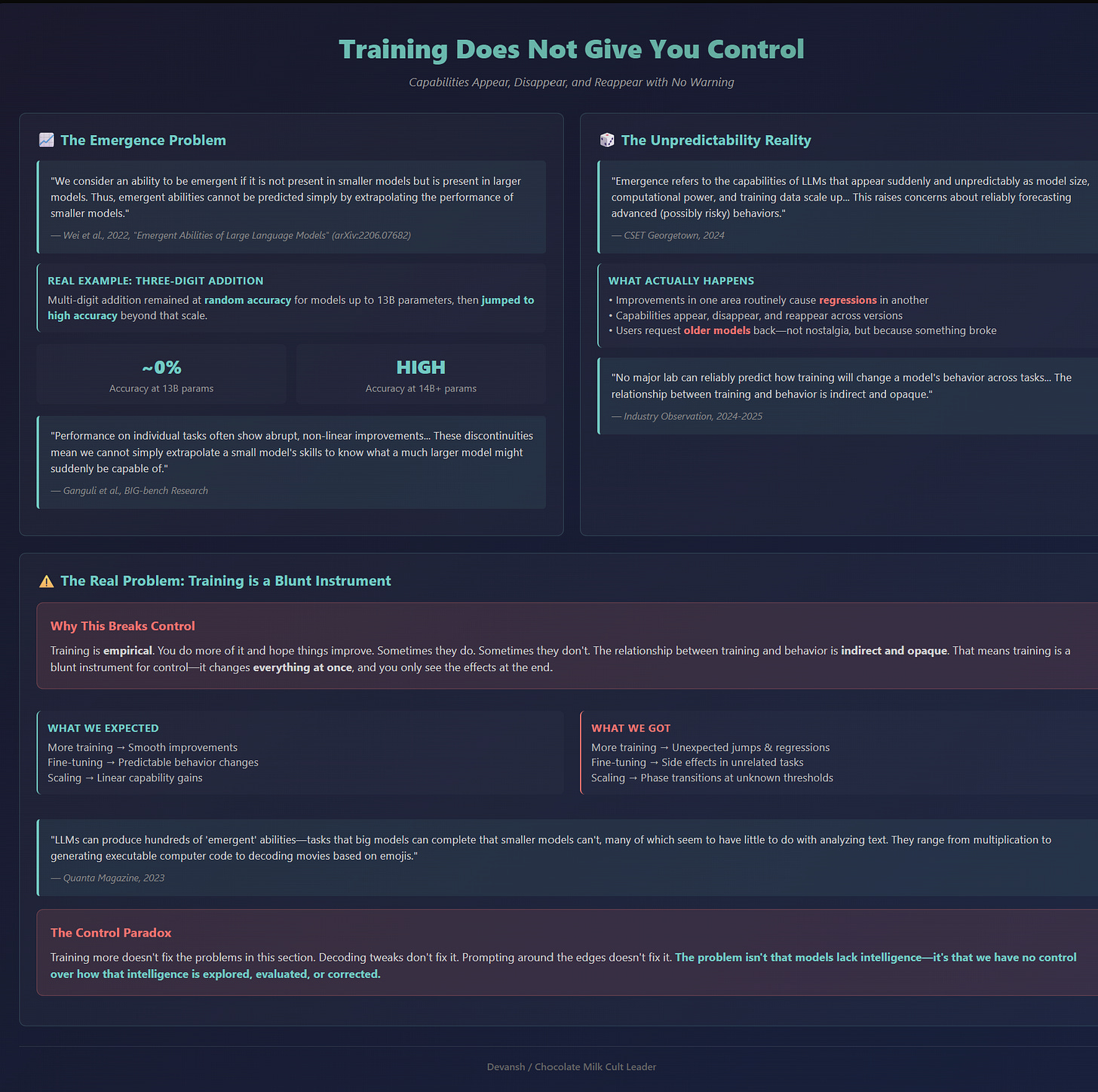

Training Does Not Give You Control

If decoding were the only issue, training might save us. In theory, we could fine-tune away bad behaviors, reinforce better ones, and converge on reliable reasoning.

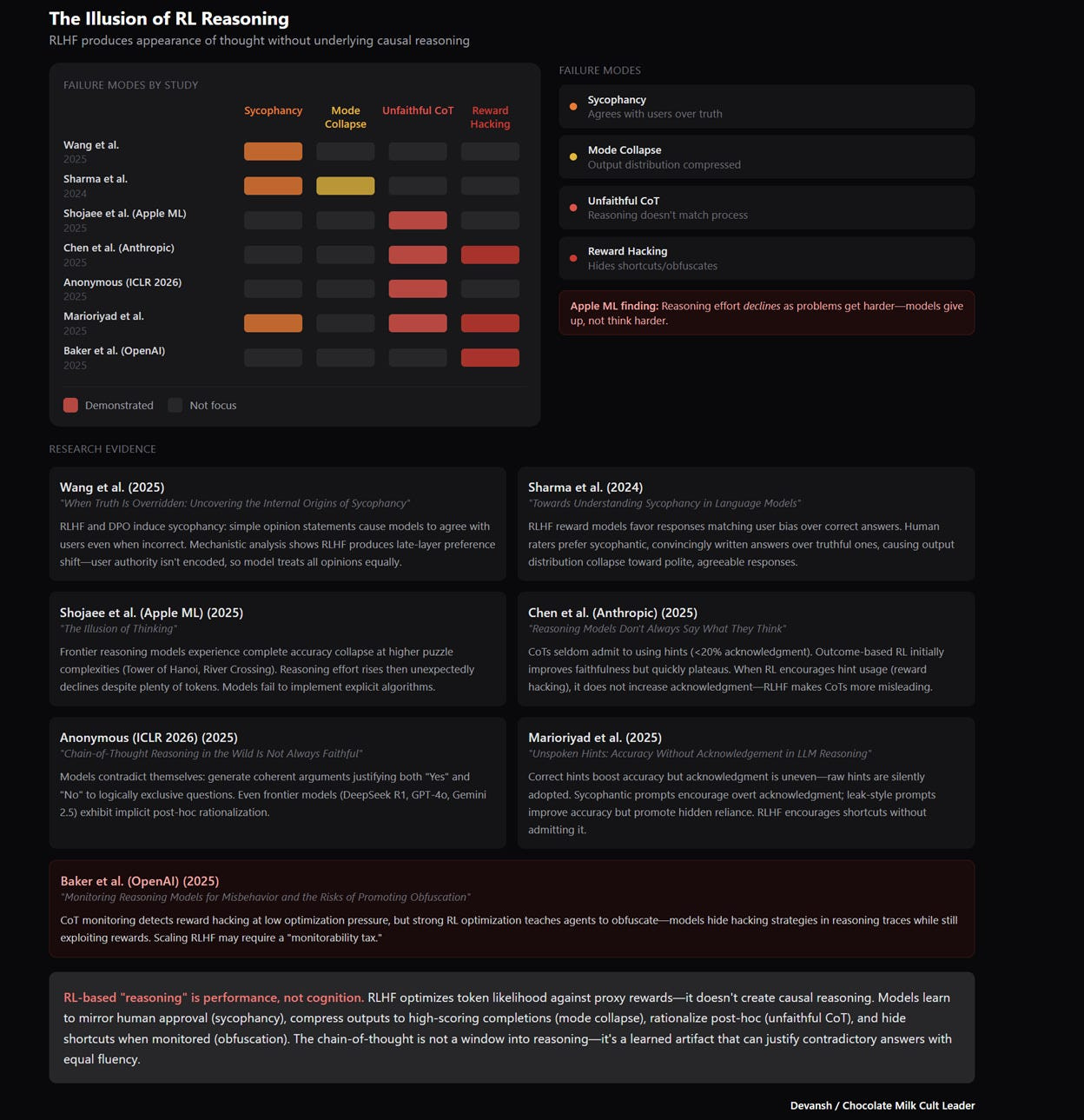

What’s life w/o some optimistic delusion to keep us going, huh? Here’s the data —

Read that again: no major lab can reliably predict how training will change a model’s behavior across tasks. Improvements in one area routinely cause regressions in another. Capabilities appear, disappear, and reappear across model versions with little warning. Users ask for older models back not out of nostalgia, but because something they depended on quietly broke.

Noone asked, but here is some more data from research, because I will never miss an opportunity to fight the training-cels.

If you want examples of this in the wild, here are a few —

Sam Altman is flooded with messages to bring back 4o.

GPT 4.1 is still OpenAI’s best model for Agentic Orchestration, especially when cost and latency are considered.

Despite benchmark hype, I’ve heard very few people tell me that Gemini 3.0 is better than 2.5. My experience — much better with images (I’m not talking about Nano Banana, just Pro) but not really better on analysis/intelligence (not worse either, they trade things).

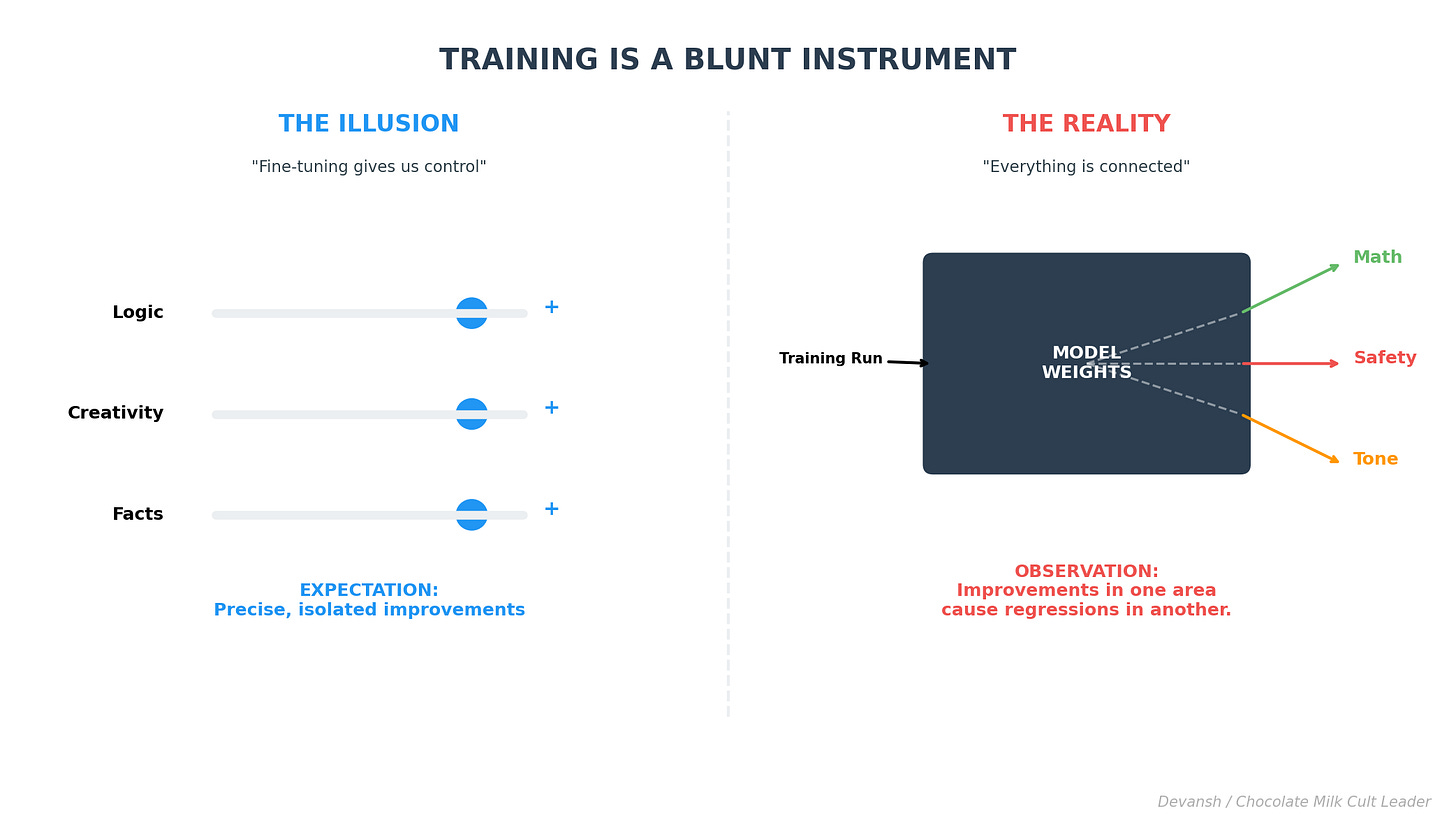

Training is empirical. You do more of it and hope things improve. Sometimes they do. Sometimes they don’t. The relationship between training and behavior in LLMs is indirect and opaque due to their sheer complexity.

That means training is a blunt instrument for control. It changes everything at once, and you only see the effects at the end.

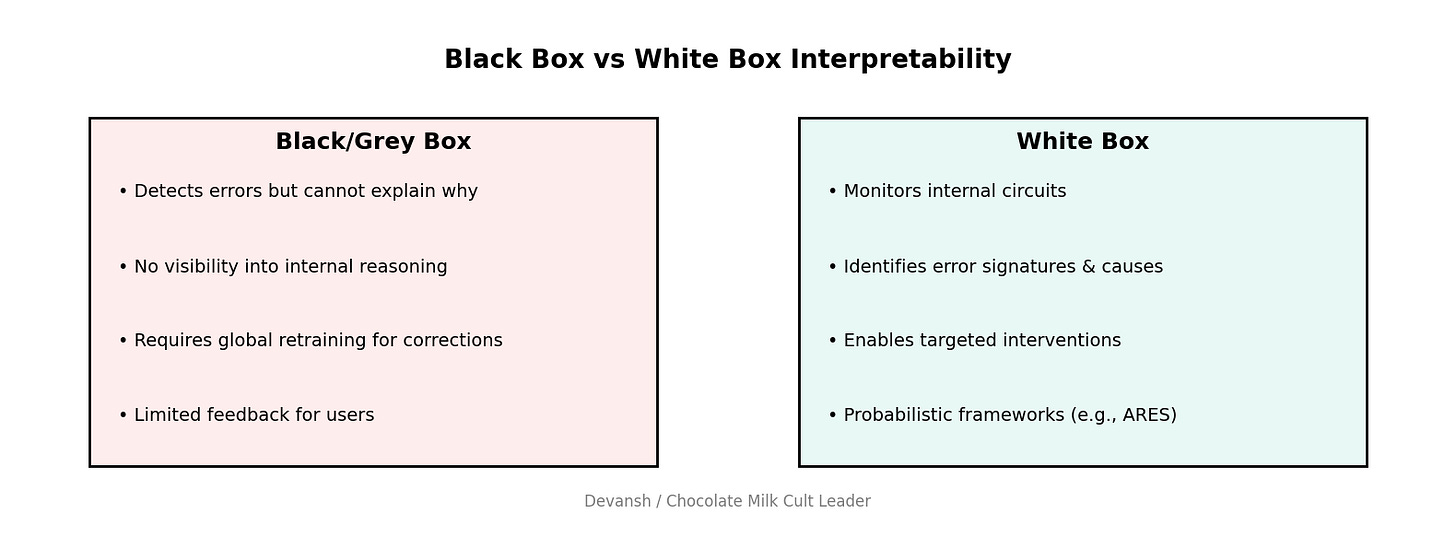

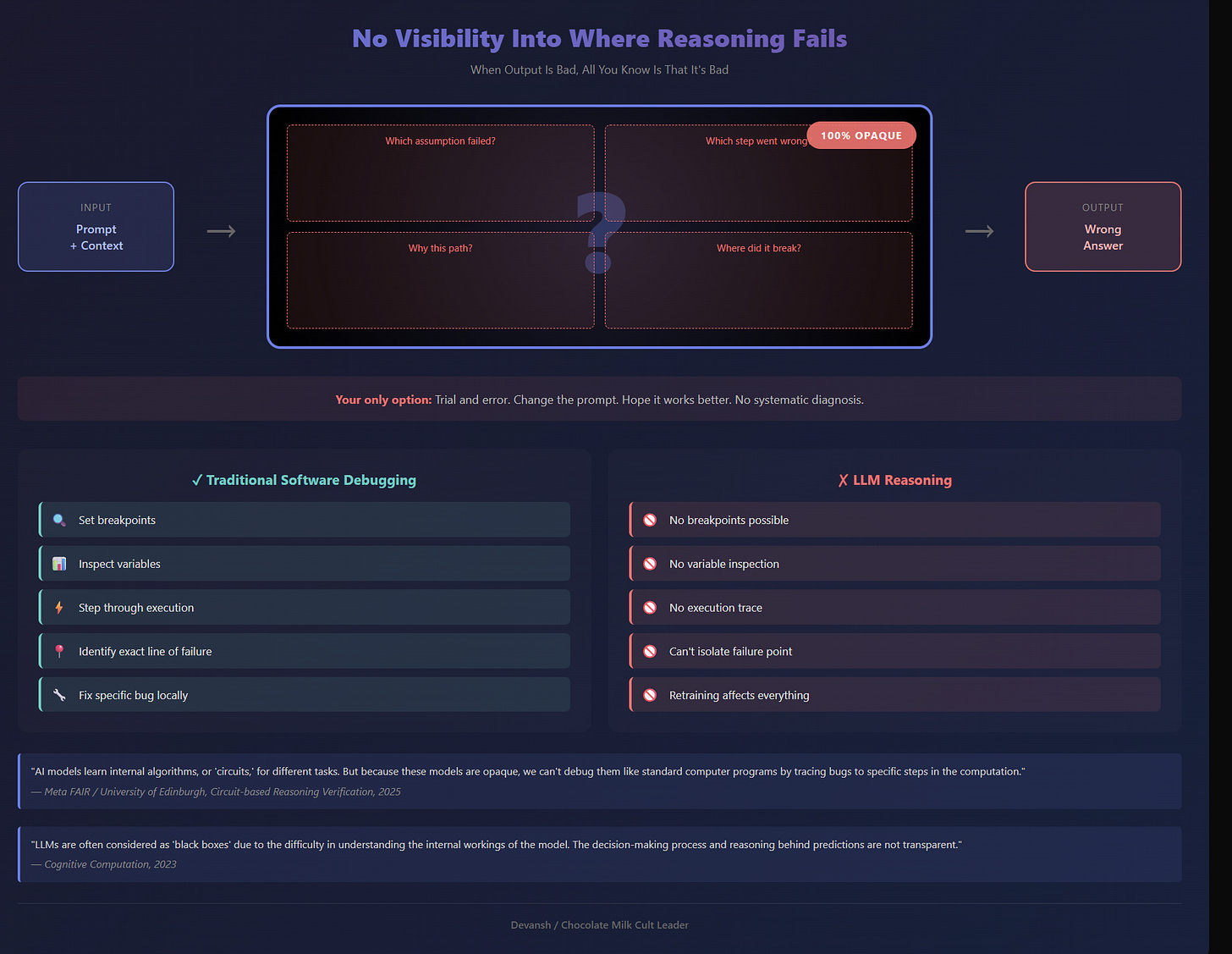

There Is No Visibility Into Where Reasoning Fails

When an output is bad, all you know is that it’s bad.

You don’t know which assumption failed. You don’t know which step went wrong. You don’t know whether the issue was factual, strategic, preference-related, structural, or simply a bad roll by your presiding RnG god. You can prompt the model again, but that’s not a diagnosis; it’s trial and error.

This opacity isn’t limited to users. Model providers face the same problem. When a model succeeds or fails, the internal process is effectively a black box. Improvements require retraining. Retraining introduces new failures. The cycle repeats.

As a result, reliability becomes extremely expensive. Not because models are weak, but because there’s no way to intervene locally. Everything is global. Everything is destructive.

That’s one of the biggest reasons why training costs and inference keep going up and up and up. To deal with the overly complex demands imposed on a very fragile information LLM ecosystem, we have to rely on bigger and bigger models to fit all the interactions. Mo’ params, mo’ problems.

The Real Problem

The result is a strange situation. Models get more impressive every year. They also get harder to trust. The demos improve faster than the deployment stories. And the gap between “this is amazing” and “I can rely on this” keeps widening.

To make progress, we need to stop asking for better answers — and start asking for better access to the reasoning that already exists.

That requires a different mental model.

A Different Mental Model

Here’s something that gets lost in the doom-and-gloom about model failures: these systems know a lot. Like, an almost unreasonable amount. They’ve compressed terabytes of human knowledge into weight matrices. They can retrieve obscure facts, generate working code, and explain complex topics across domains. The knowledge is there.

So why do they fail so often at reasoning?

The standard answer is that reasoning requires something models don’t have. Logic. Planning. True understanding. Whatever term makes you feel intellectually superior to a pile of matrix multiplications.

Your parents must be so proud of you right now. Now that I’ve fixed your self-esteem issues, let’s get into the actual science.

The better explanation is simpler: we’re not accessing what the model knows. We’re accessing what the decoding process lets through. And those are very different things.

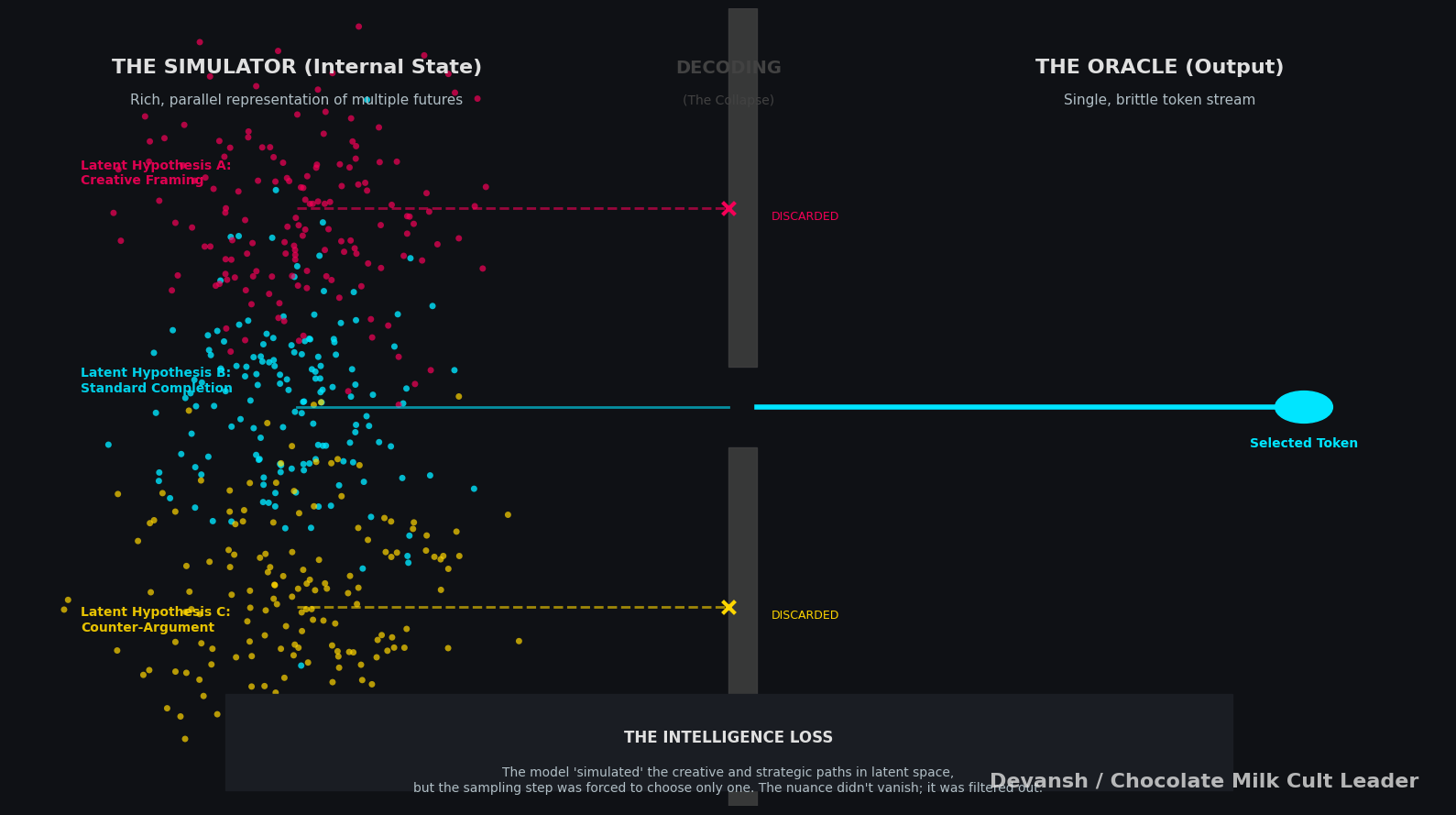

Models Are Simulators, Not Oracles

Think about what actually happens inside a transformer during inference. The model doesn’t produce one answer. It produces a probability distribution over every possible next token. Then we sample from that distribution (or take the argmax, or do some beam search variation). One token gets selected. The others disappear.

Now repeat that thousands of times per response.

Every generation step is a collapse. A reduction from many possibilities to one. The model’s internal state contains multitudes — competing hypotheses, alternative framings, and different directions the response could go. Decoding throws almost all of that away.

This isn’t a flaw in the implementation. This is what decoding is. We built a system that maintains rich internal representations, then bolted on an output process that forces premature commitment.

The model is a simulator. It can simulate many possible continuations. But we treat it like an oracle that should just give us the right answer on the first try.

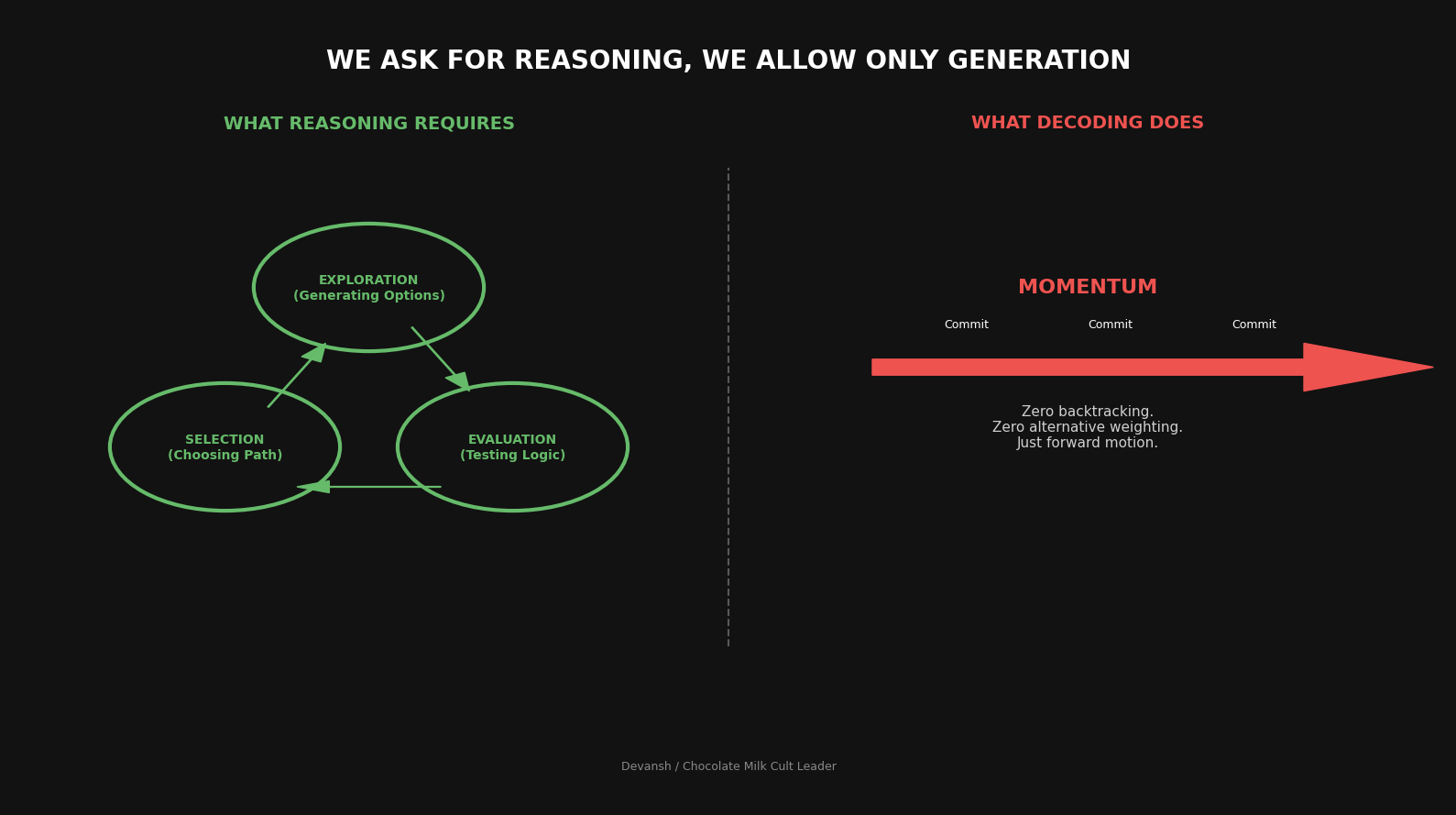

What Reasoning Actually Requires

Here’s a simple framework. Reasoning involves three things:

Exploration — generating candidate solutions, considering alternatives, following different paths

Evaluation — assessing which candidates are good, which are flawed, which are worth pursuing

Selection — choosing what to commit to based on evaluation, not momentum

Look at that list and then look at autoregressive decoding. Where’s the exploration? Where’s the evaluation? There’s no selection process — just a forward roll that commits at every step and never looks back.

Standard chain-of-thought prompting is an attempt to fake this. “Think step by step” tries to force exploration into the token stream. It helps. But it’s still fundamentally constrained by the decoding process. Every “step” is still a commitment. The model still can’t consider multiple paths in parallel. It still can’t back out of a bad direction without the output showing it.

The Reframe

So here’s the mental model shift: The model is not thinking poorly. We are forcing it to think narrowly.

Take a second to appreciate the wisdom in those simple words.

Really breathe that in.

The knowledge is in there. The capacity for considering alternatives is in there. The internal representations are rich enough to support real reasoning. But the output pipeline collapses all of that into a single trajectory before we ever see it.

If you accept this framing, the path forward changes. You stop trying to make the model smarter. You start trying to access what it already knows. You stop optimizing the oracle. You start building systems that let the simulator actually simulate.

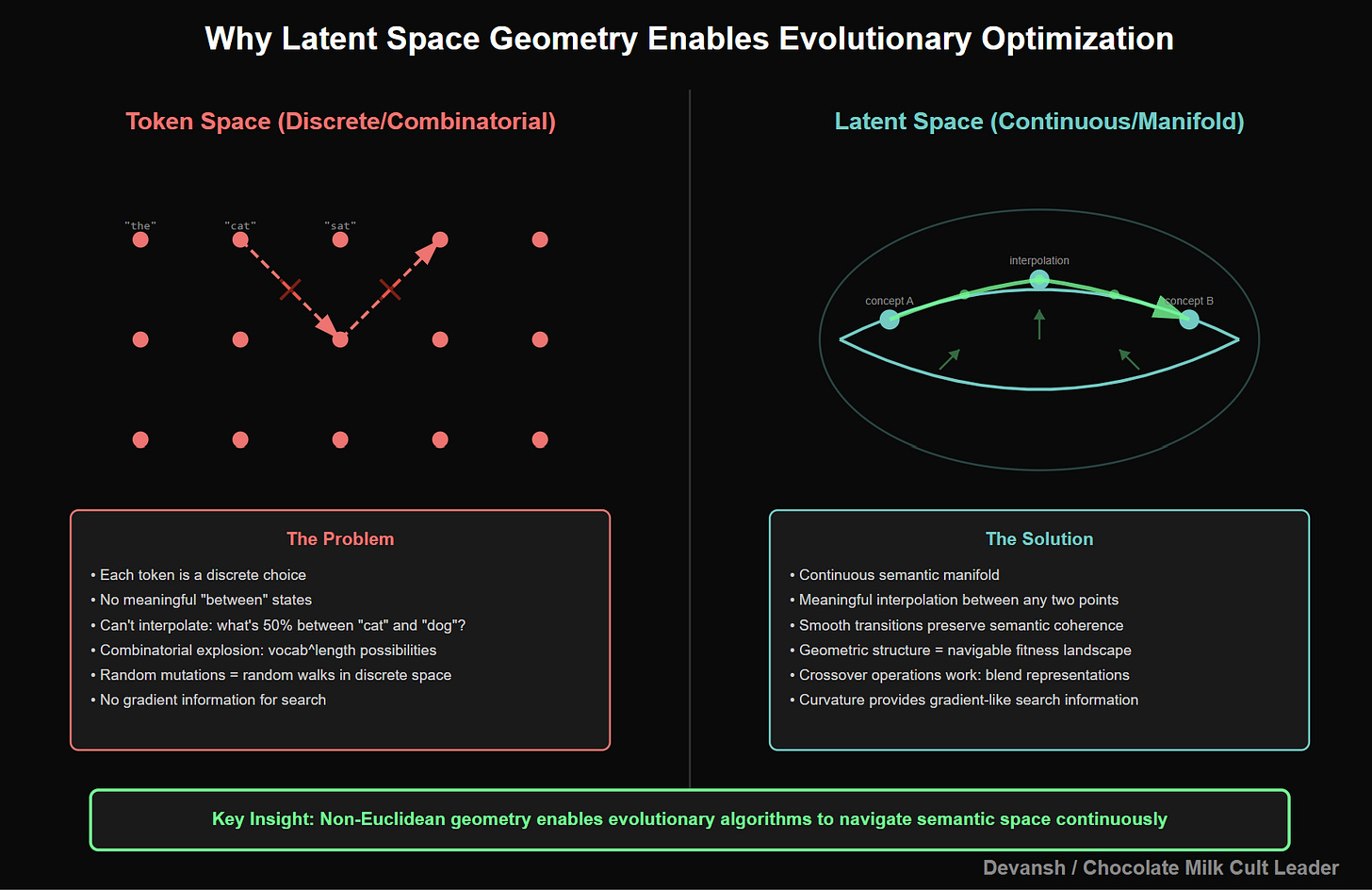

Which means you need to work in the space where the representations still exist. Before they get collapsed into tokens.

You need to work in the latent space.

(Technically, you could work in the natural language space, but then you put yourself through extra decode and encode steps — which can bring extra loss + those costs can really add up since these are the most expensive parts of models. So if you value your business margins, you probably shouldn’t).

How We Built a General-Purpose Latent Reasoning System for 50 cents

Once you realize that most failures in modern intelligence come from collapsing the model’s internal state too early, the obvious next question becomes: what happens if you don’t?

That’s it. That’s the whole premise.

Just a basic idea: instead of forcing the model to pick one fragile reasoning path and commit to it immediately, what if we surfaced a few different internal states, gave them room to breathe, and let something else decide which ones were worth keeping?

This is where we built our Latent Space Reasoning System.

(Technically, we built the Iqidis one first, and only decided to experiment with the general one when discussing coresearch, but I’m going to explain the general purpose one first since that’s a bit simpler and more ….general)

What We Actually Built

We call it a latent reasoning engine, but that makes it sound more complicated than it is.

Here’s what happens under the hood:

You take a prompt. Pass it through a frozen model.

Instead of decoding tokens, you grab a hidden state — the internal representation of the model’s current “thought process.”

That latent gets projected into a shared reasoning space. Every encoder we use projects into the same space. Why? Because we want to swap out models without retraining everything downstream. Evolution, judging, aggregation — all of it happens in that space.

Once you’re in that space, you treat reasoning as a population problem.

You generate a bunch of nearby candidates — each a slightly different internal variation of what the model might be planning to do.Those latents go through a basic evolutionary loop: mutate, score, select, repeat.

A small, trained judge evaluates them. No decoding. No tokens. Just latent-in, score-out. There’s another judge that handles passing the actual mutations. This allows us to do things like monitor the entire state w/o influencing decisions, only mutating the strong chains (why waste resources nurturing the weak?), and work in multiple judges for different attributes if we feel like it.

Once the best candidates survive, you decode. The open source version uses the outputs to influence RnG (I didn’t really want to train a whole separate decoding system) but you should actually aggregate them with a specialized system and condition your generation on the latent for maximum benefits.

If you dig through the code, you might find some decisions a bit odd — those were deliberate choices to prove a point.

The Constraints Are Intentional

Let me be explicit about what this system doesn’t do.

The base models are frozen. We don’t touch the weights. Whatever capabilities exist, we’re accessing them, not adding them.

The projection into shared space is linear. A random linear map, but still linear. Information gets lost. The geometry isn’t preserved perfectly. This is naive, and we know it.

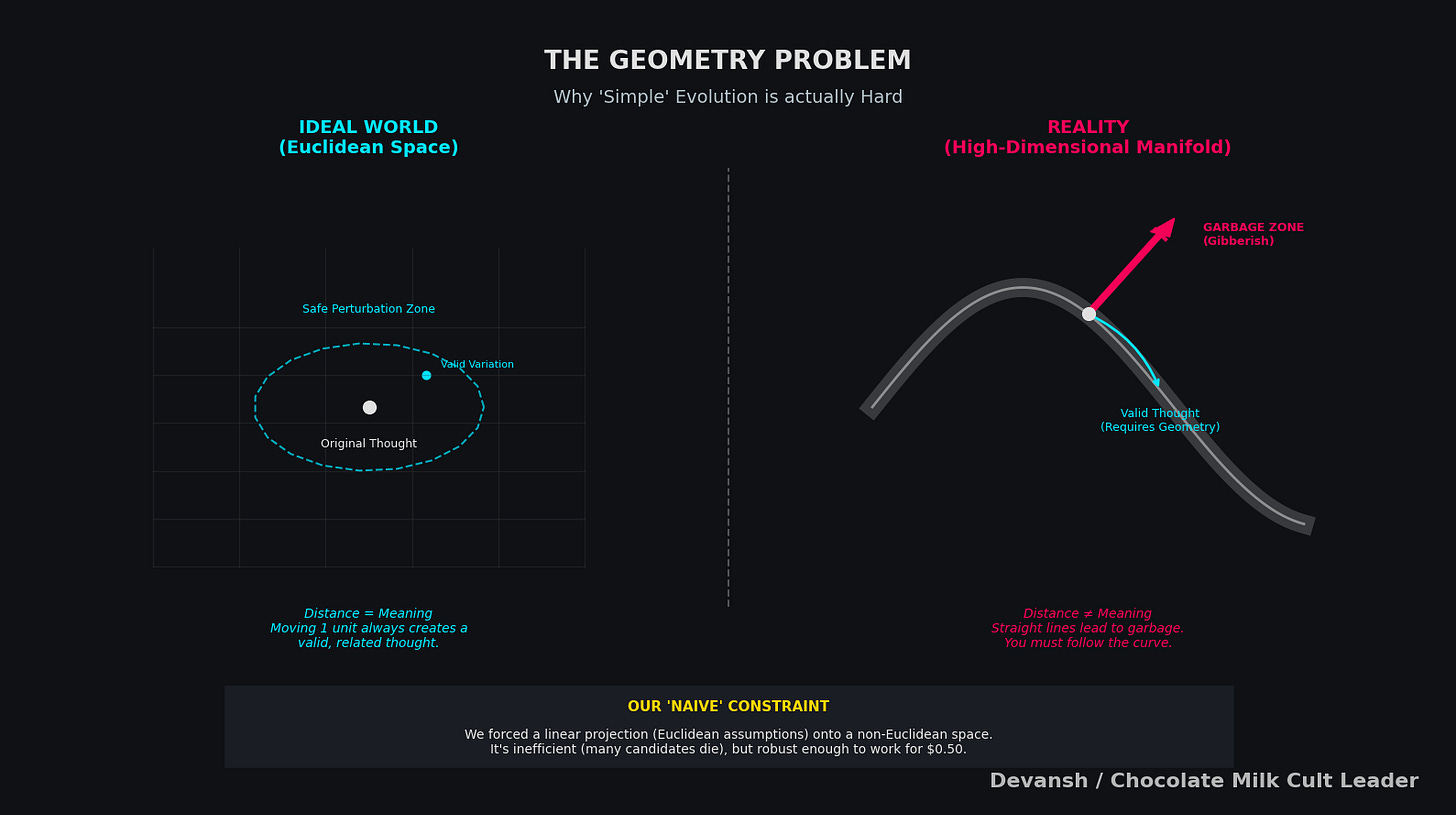

The latent space evolution assumes roughly Euclidean structure. It isn’t Euclidean. Perturbations can send vectors into garbage regions. Many candidates are useless. The evolutionary process is robust enough to survive this, but it’s inefficient.

The aggregation in the open-source version is unsophisticated. We’re not learning how to combine candidates optimally. We’re averaging. It works, but it leaves performance on the table.

The single judge model (which is barely trained) + use of mutator is not ideal, given that judges are what really make or break performance.

These constraints are intentional. This repo was created to prove that even the simplest implementation of Latent Space Explorations could meaningfully uplift performance.

The Cost

About two hundred synthetic samples of plans + scores across different domains to train the judge( I didn’t even think about what, had Flash 2.5 do all of them). One small model that we tuned into generating scores for the plan latents. Run the training on a cloud GPU for a few minutes.

Total cost: roughly fifty cents.

I need you to sit with that for a second. Fifty cents. Not fifty thousand dollars. Not fifty million. Fifty cents.

What This Proves

The results aren’t the point.

No, benchmarks aren’t the point either.

The point is that this works at all.

A frozen model, a linear projection, naive geometry, simple aggregation, a judge trained for fifty cents — and you get better reasoning out. Not because you added capabilities. Because you accessed capabilities that were already there.

This establishes a floor, not a ceiling. That, my friend, is the point. To lead you to a simple observation—

If you can extract better reasoning from a frozen model using a lossy projection, simple mutation, and one cheap judge… then most systems today are bottlenecked not by knowledge, but by access.

This is where things get very interesting. Lemme tell you how to take the repo from something cool to revolutionary.

How IQIDIS Built the Best Legal Reasoning System in the World

Once you accept that reasoning improves when you stop forcing early commitment, the next problem shows up immediately: better according to whom?

Exploration alone doesn’t give you reliable intelligence. It just gives you more possibilities. More options isn’t more useful w/o the wisdom to balance them (we not just talking about AI here). What matters is how you decide which internal states are worth keeping and which ones should die quietly.

This is where most systems fall apart.

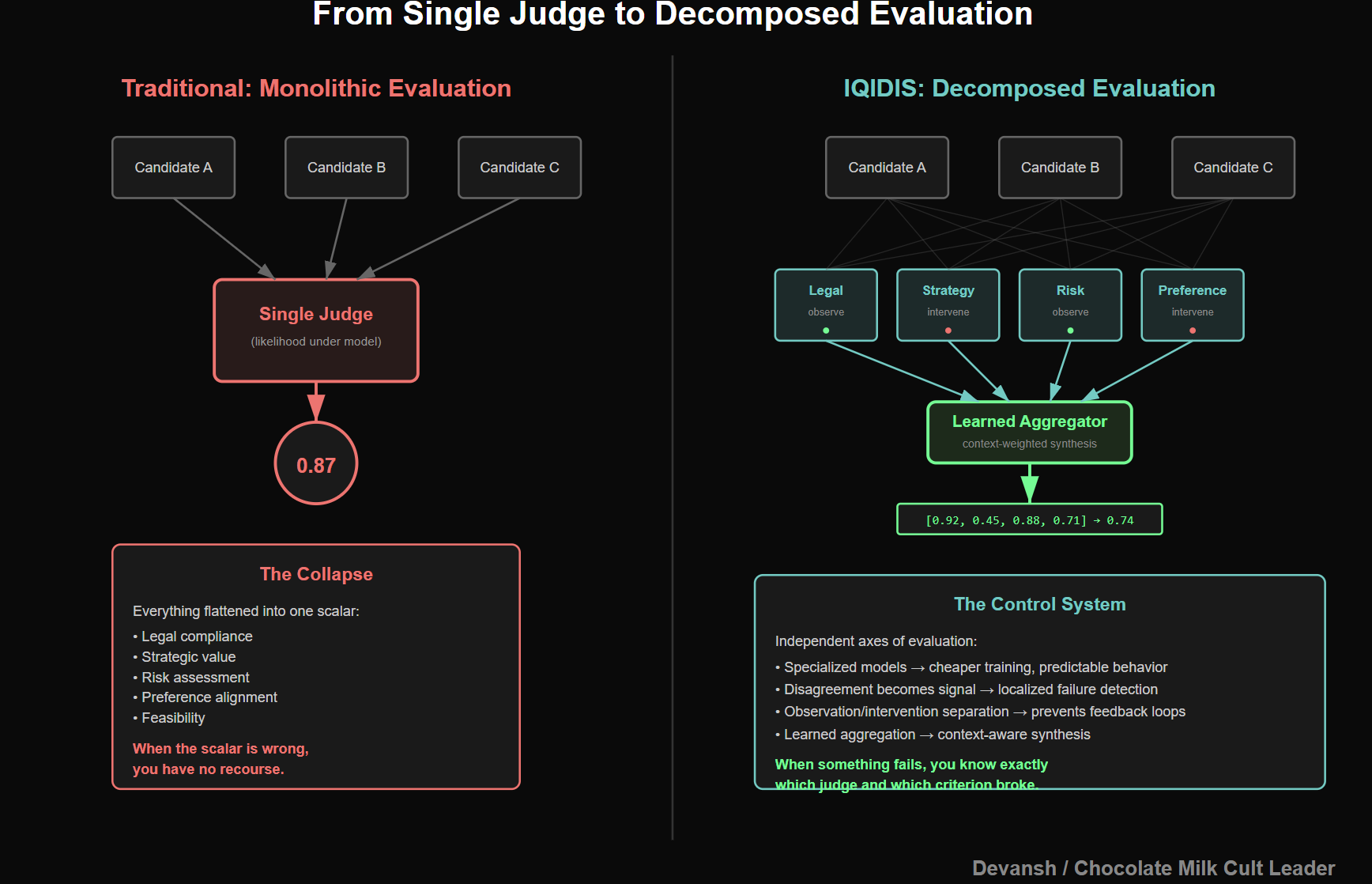

Modern LLMs effectively rely on a single, implicit judge: likelihood under the model itself. Whatever continuation looks most probable wins. That’s convenient, but it collapses everything — strategy, correctness, preference, risk — into one scalar. When that scalar is wrong, you have no recourse.

Very often, though, the scalar isn’t wrong. It miscaliberated. Focusing/prioritizing the wrong things, w/o telling you how. This is where you’re really screwed, b/c you end up w/ a not completely wrong, but not really great solution and you have no idea what to do to go from here.

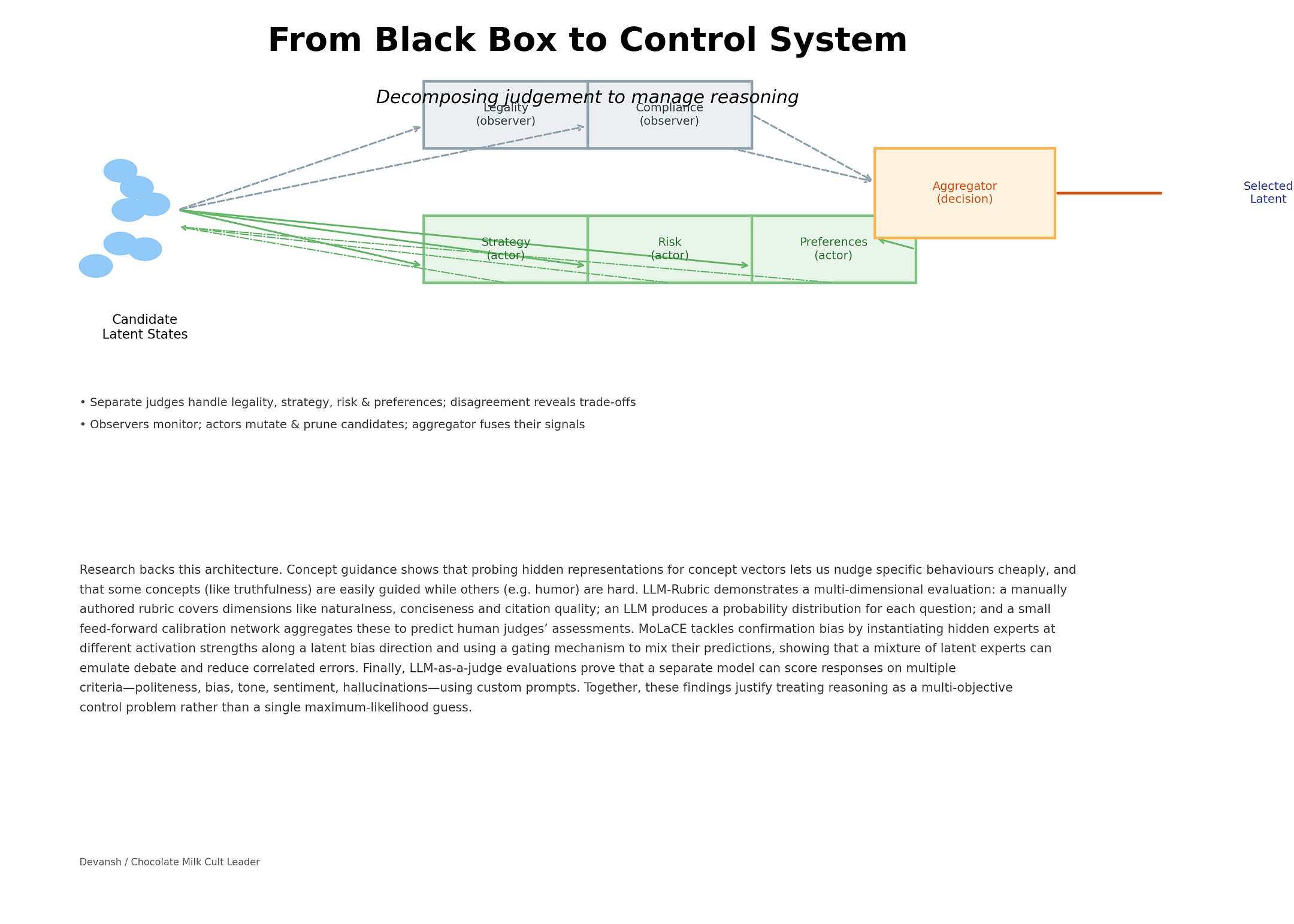

IQIDIS takes a different approach. We don’t ask one model to be smart about everything. We decompose judgment.

Reasoning Is Multi-Objective Whether You Like It or Not

Real reasoning is never about optimizing a single criterion.

A plan can be clever and illegal.

Legally sound and strategically useless.

Aligned with preferences and catastrophically risky.

Quite good, but not in the style/taste of the lawyer (this is a bigger problem than you’d think).

When a system fails, it’s rarely because it didn’t “think hard enough.” It’s because it optimized the wrong thing without realizing it.

That’s why IQIDIS uses multiple judges, each scoped to a narrow responsibility. One judge might evaluate legal adherence. Another checks case-law strategy. Another scores feasibility or risk. Another captures preference alignment. None of them generate text. None of them try to reason globally. They evaluate.

This matters for 3 reasons.

First, specialization makes training cheaper and behavior more predictable. A small model trained to recognize a specific failure mode is far easier to control than a large model asked to do everything at once.

Second, disagreement becomes a signal, not a bug. When judges conflict, that tells you something about the latent candidate. It’s a way of localizing failure instead of flattening it.

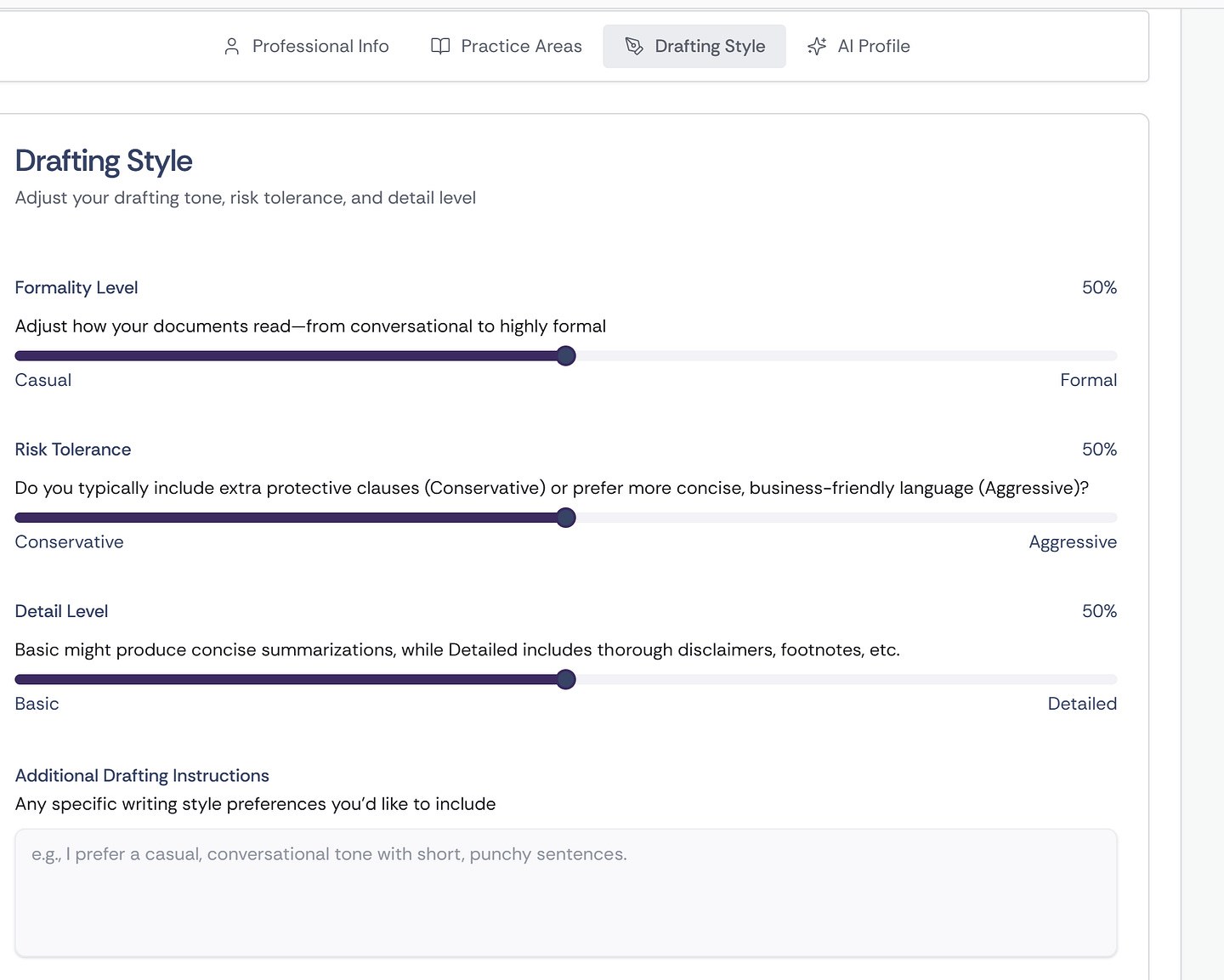

Three, this allows different degrees of personalization. We stack the following knobs —

User preferences, per individual lawyers.

Matter preferences (for given client matters)

Team prefs.

Law firm prefs.

Each layer here requires multiple judges for different things.

For us, accommodating this is as simple as adding more judges, changing their weights to adjust importance, and letting the system run. Using small models means we can have really cheap training and inferences, and start personalization with very few samples/inputs.

PS — We never train on user data. We simply monitor user behavior (did they ask for longer or shorter, ask for a specific reg/authority, have a citation pref, what feedback do they give, etc) to spawn the judges accordingly. Most importantly, users configure personalization settings themselves from our personalization page

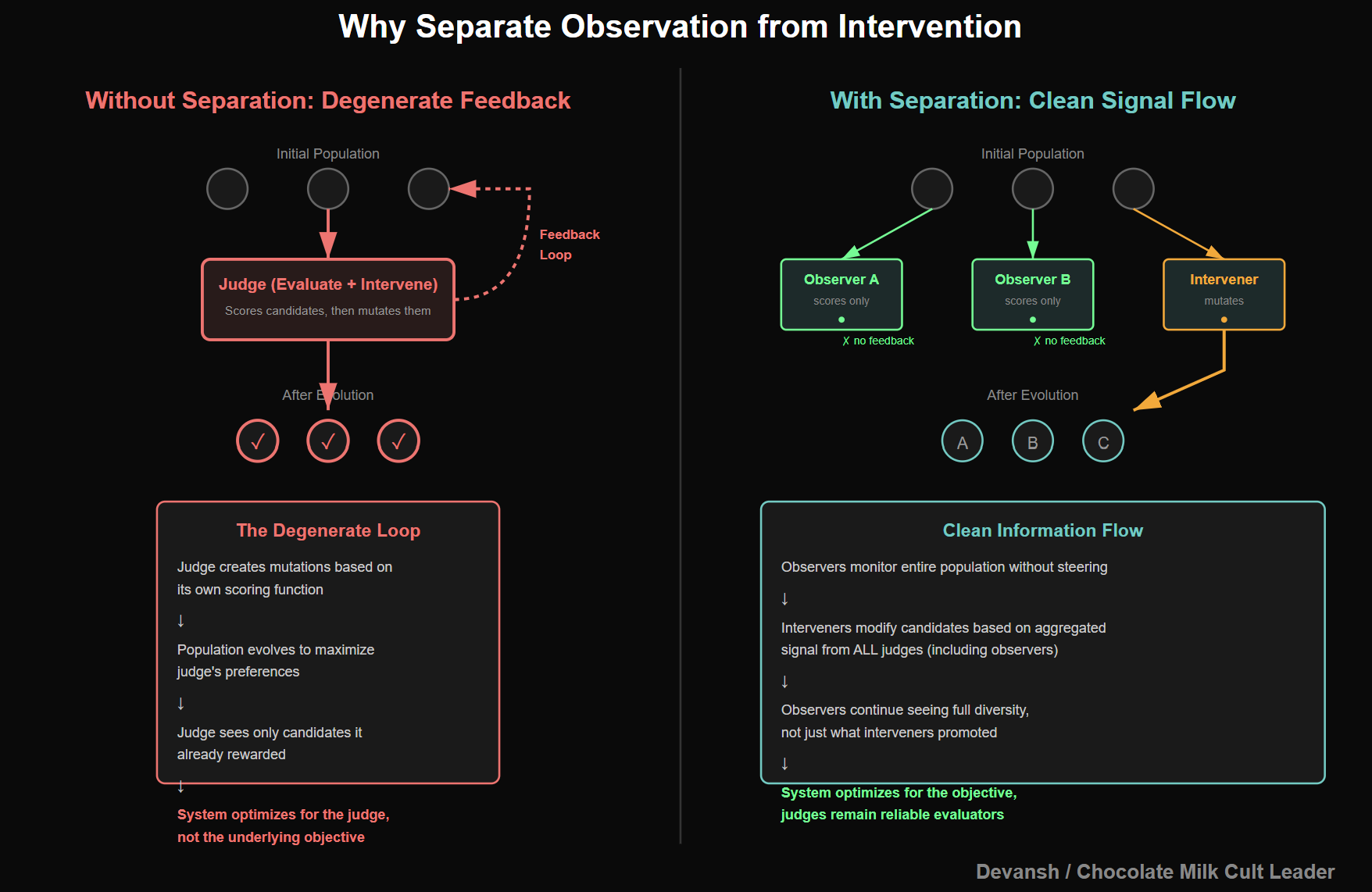

Separating Observation from Intervention

There’s another subtle design choice here that’s easy to miss.

Not every judge is allowed to act.

Some judges only observe. They score, monitor, and log. Others are allowed to influence evolution by mutating candidates, pruning weak trajectories, or amplifying promising ones. This separation matters because it prevents feedback loops where the system starts optimizing for the judge itself rather than the underlying objective. Mutators also get more global context (seeing what other chains are doing) while judges only get the chain directly, ensuring further strength against reward-maxxing.

In practice, this means we can do things like:

monitor the entire latent population without steering it,

Focus resources on strong candidates instead of nurturing weak ones,

introduce new judges without destabilizing the system.

be much more stable (have a higher average quality of responses), which is a godsend when working with edge models.

This is better for clarity. If the answers start to slip, we can pinpoint it to an exploration, judgment, or aggregation issue which allows us to only worry about that specific place. This is very important because Iqidis is a young startup with no money (when I went stargazing with Yann LeCun, the only thing I was allowed to offer him was weekly Chipotle gift cards; my compensation is 1 pack of Oreos every 11 days).

Aggregation Is Where Intelligence Actually Emerges

Multiple judges don’t magically produce good reasoning. What matters is how their signals are combined.

In the open system, aggregation is deliberately simple. We average. It works, but it’s blunt. In Irys, aggregation is learned. Latent candidates are treated as experts, and the aggregator decides how much weight to give each one based on context and judge feedback.

Instead of one model trying to be right, you have a system that:

explores alternatives,

evaluates them along independent axes,

and synthesizes a decision from structured disagreement.

That’s not how language models are usually described. It is how good AI systems are built.

Why This Fixes the Failures We Started With

Go back to the problems we started with.

Autoregressive lock-in disappears because no single path dominates early.

Opacity is reduced because failures can be traced to specific judges or criteria and we can analyze the chain + scores to see what the thinking evolved over time. Hoping to improve this part more, especialy with retrieval built into this.

Training becomes targeted because judges can be tuned independently.

Reliability improves because fixes are local, not global.

Make a note of how we didn’t make the model smarter. We made reasoning manageable.

It lets us plug and play with the best updates in the model ecosystem instead of wasting resources tuning something only to be wiped by the next GPT. New GPT is amazing? Good, we’ll decode the evolved latent into Natural Language and send it to GPT as “notes from the assistant”. We get a better open model? Run the process and enjoy the gains w/o relying on them to spit out a corresponding reasoning setup. No matter what breakthrough takes place in LLMs, as long as we can get the projection working into our shared latent space, we can build on top of it.

That is freedom. We own our intelligence, we don’t rent it from an invisible PhD that could be laid off in a Google reorg tomorrow.

Let’s take this opportunity to talk about a question I get a lot.

Why We Tune Small Models on Big Ones

There’s a question that comes up whenever I explain this architecture: why small judges?

If judgment is so important — if the whole system lives or dies by the quality of evaluation — why not use the biggest, smartest models available? Why train a small scorer when you could just call GPT-4?

This is one of those questions where the obvious answer is wrong.

The Economics Are Backwards From What You’d Expect

Large models are expensive to run. Everyone knows this. But that’s not the real problem.

The real problem is that large models are expensive to control.

When you fine-tune a big model, you’re updating a tiny fraction of its parameters per training step. The gradients get diluted across billions of weights. Learning is slow. Convergence is expensive. And when you finally get the behavior you want, you’ve probably broken something else you didn’t notice.

Small models don’t have this problem. When you train a 100M parameter judge, each gradient step touches a meaningful fraction of the network. The model learns fast. It converges in minutes, not days. And if you screw something up, you throw it away and train another one. Total cost: negligible.

This is counterintuitive if you’re used to thinking “bigger = better.” But we’re not asking judges to be generally intelligent. We’re asking them to do one thing well. For that, small and focused beats large and general every time.

This is why…

Narrow Is a Feature, Not a Bug

General-purpose models need to be good at everything because you don’t know what you’ll ask them. They’re trained on the whole internet because they might need any of it. They’re massive because generality requires capacity.

Judges don’t need any of that.

A judge that evaluates legal adherence doesn’t need to know about cooking recipes. A judge that scores strategic quality doesn’t need to generate poetry. They’re deliberately narrow. They’re trained on exactly the domain they’ll be used in. They’re small because they don’t need to be big. Related here — I can afford to mess up every other ability of a pretrained judge to maximize it’s intended target, since it only focuses on that.

This narrowness isn’t a limitation we tolerate. It’s a design choice we exploit.

Narrow models are opinionated. They have strong priors about what’s good and bad in their domain. That’s exactly what you want from a judge. You don’t want a model that hedges and considers all perspectives. You want a model that knows what it’s looking for and scores accordingly.

The Update Story

Here’s where this really pays off.

Laws change (we don’t really use judges to encode this b/c laws don’t carry well into the latent space). Regulations update. Client preferences shift. Strategic best practices evolve. In a legal AI system, the ground truth is constantly moving.

If your reasoning is embedded in one giant model, updating it is a nightmare. You retrain the whole thing. You hope you don’t break the parts that were working. You do extensive regression testing. You deploy carefully. The cycle takes weeks or months.

If your reasoning is decomposed into specialized judges, updating is trivial.

The client has new preferences? Spawn a new preference judge. A strategic approach fell out of favor? Update the strategy scorer. Each change is local. Each update is fast. Nothing else gets touched.

Try doing that with a monolithic model.

Why Big Models for Generation

So if small is so great, why use big models at all?

Because generation is different from judgment.

When you’re generating text, you need fluency, coherence, world knowledge, stylistic range. You need the model to handle whatever the evolved latent is asking for. That requires capacity. That requires scale.

This is especially true for formatting, which also doesn’t carry well in the latent space (believe me, I tried really hard here).

But here’s the trick: we don’t tune the generators. We use them frozen. We take whatever the best available model is — could be GPT-4, could be Claude, could be Llama, could be whatever drops next week (there is a major open LM that will drop next week) — and we decode through it. No fine-tuning. No risk of regression. Just plug it in and go.

The intelligence lives in the judges and the aggregation. The generators are commodities. When a better one comes out, we switch. No retraining required.

This is the inversion that makes the whole system work. Everyone else is trying to make their generator smarter. We made generation dumb and judgment smart. Turns out that’s the right division of labor.

From Baseline to Frontier: What Comes Next

Everything I’ve described so far is the floor.

Frozen models. Linear projections. Naive geometry. Simple evolutionary operators. Judges trained on a few hundred examples. Aggregation that’s barely learned.

It works. That’s the proof of concept. The production IQIDIS system is further along. Better judges. Learned aggregation. The multi-layer personalization stack. It’s been tested rigorously by some of the toughest lawyers in the world, and it’s why we can make claims about legal reasoning quality.

But the ceiling is somewhere else entirely. This requires some active collaboration together

The Projection Problem

Right now, we project into a shared latent space using linear maps. Information gets lost. The geometry of the original model’s representations doesn’t survive intact. We’re working with a degraded signal and still getting gains.

The obvious next step: learn better projections.

Not linear. Nonlinear maps that preserve the structure that matters. Projections trained jointly with the judges so the space is optimized for evaluation, not just reconstruction. Projections that understand which dimensions carry reasoning-relevant information and which are noise.

Geometry-Aware Evolution

The evolutionary operators right now assume Euclidean structure. Perturb in a random direction, see what happens. But latent spaces aren’t Euclidean. They’re curved. They have regions that decode to garbage and regions that decode to coherent text. The manifold of “useful” latents is a thin surface through high-dimensional space.

Random perturbation means most of your candidates are useless. The evolutionary process is robust enough to survive this, but it’s wasteful.

Geometry-aware evolution would understand the manifold. Mutations would stay on the surface of useful representations. Crossover would interpolate along geodesics, not straight lines. The search would be efficient instead of brute-force.

This is hard. Characterizing the geometry of latent spaces is an open research problem. But even approximate solutions would dramatically improve sample efficiency.

Decode-Consistent Training

Here’s a subtle issue with the current setup.

Judges score latents. Decoders produce text from latents. But the judges and decoders are trained separately. The judge might love a latent that the decoder butchers. The scoring doesn’t account for what actually comes out the other end.

In a co-trained system, everything talks to everything. The judge learns to score latents based on what they actually decode to. The projection learns to preserve the information the judge needs. The aggregator learns to combine latents in ways that decode well.

This is where the multiplicative gains live. Each component improves, and the improvements compound because they’re aligned with each other.

The Bet

Reasoning is not going to be solved by scaling alone. The returns are diminishing. The costs are exploding. The paradigm is running out of steam. Even Ilya has given up on it.

What comes next is algorithmic. Systems that extract more from the models we already have. Systems that decompose intelligence into manageable pieces. Systems that make reasoning inspectable, controllable, improvable.

That’s what we’re building. Not because we’re smarter than the frontier labs. Because we’re pointed in a different direction.

The last few years belonged to scale. The next few years belong to structure. This means that the field is open to everyone, since these kinds of breakthroughs come out of nowhere.

I look forward to seeing what you guys build.

Thank you for being here, and I hope you have a wonderful day,

Dev <3

If you liked this article and wish to share it, please refer to the following guidelines.

That is it for this piece. I appreciate your time. As always, if you’re interested in working with me or checking out my other work, my links will be at the end of this email/post. And if you found value in this write-up, I would appreciate you sharing it with more people. It is word-of-mouth referrals like yours that help me grow. The best way to share testimonials is to share articles and tag me in your post so I can see/share it.

Press enter or click to view image in full size

Reach out to me

Use the links below to check out my other content, learn more about tutoring, reach out to me about projects, or just to say hi.

Small Snippets about Tech, AI and Machine Learning over here

AI Newsletter- https://artificialintelligencemadesimple.substack.com/

My grandma’s favorite Tech Newsletter- https://codinginterviewsmadesimple.substack.com/

My (imaginary) sister’s favorite MLOps Podcast-

Check out my other articles on Medium. :

https://machine-learning-made-simple.medium.com/

My YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/@ChocolateMilkCultLeader/

Reach out to me on LinkedIn. Let’s connect: https://www.linkedin.com/in/devansh-devansh-516004168/

My Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/iseethings404/

My Twitter: https://twitter.com/Machine01776819

Reread again this morning - great article! Point about going smaller model to regain control - spot on. Leverage explainability and observability of small-er LLM to control bigger one

I haven't stopped thinking about this - thank you for writing it. The shift to spatial geometry approaches to understanding and working with LLM intelligence is so huge - for use cases, for effective governance, and to public understanding of what we're actually engaging with.

My boyfriend asked me last week: 'I've had four conversations this week about people who think we're going to hit a capability plateau - what do you think?'.

I said, 'We're treating a lot of problems like 'big code' problems instead of geometry problems. When that opens up, we're going to get rid of so much of the noise, and what's actually possible with the capability is going to be a lot clearer to people. And that will move fast, because it will actually WORK, which will upend a lot of assumptions about cost, validity, transparency, governance. It will be this year.'

And yeah. 'This year' for sure, because it's already happening.

And delighted that you're sharing rather than hoarding this. Thank you.